Text and photo reproductions by ELIZABETH LOLARGA

>THE much-loved and esteemed Doreen Gamboa Fernandez would have been more than pleased at the culinary storm she helped generate: blogs devoted to restaurant reviews; culinary academies rising in nearly all parts of the country; regional and national cooking contests; newspaper sections and columns devoted to food and dining. In a large way, this is her doing.

Add to that, the well-traveled, widely exposed Pinoy has developed a discriminating palate that has learned to savor a multitude of tastes representing cuisines of the world.

The life and works of this modern Renaissance woman is the subject of an exhibit at the Ateneo Library of Women’s Writings (ALIWW) Reading Room on the Loyola Heights campus, Quezon City, until Nov. 9.

Apart from photographs of Fernandez and copies of her books, the glass cases display the meticulous syllabus, exams and class records she kept when she taught generations of Ateneo students English, literature, journalism and creative writing, her own notebooks and notes from graduate school where she did ground-breaking research on the history of Philippine theater under scholars Bienvenido Lumbera and Nicanor Tiongson who later became her colleagues, thank-you notes from medical residents, students and people who heard her lecture or to whom she gave her time and attention.

No wonder the Ateneo community insists, with this exhibit, on remembering what to its members is “a great woman.”

Teacher, scholar, writer, taste-maker, even “pleasant patient, strong even during the most trying of times,” in the words of the resident staff of the Makati Medical Center whom she taught how to improve their command of the English language. It was her way of giving back for their helping her recover from illness. Fernandez wore these inter-related hats with elan, unselfishness and humility.

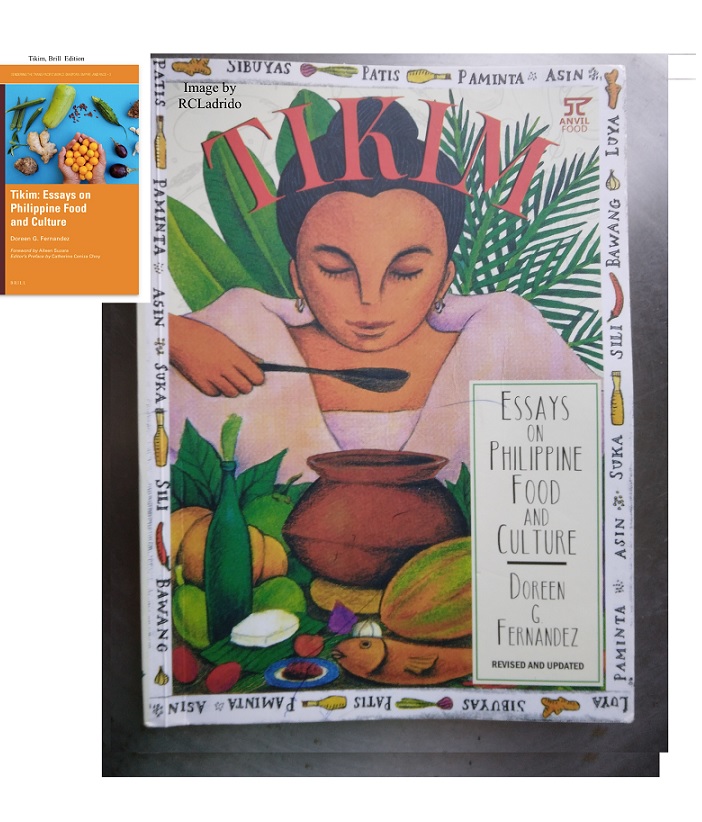

Unselfish and humble because she did not hog credit to herself, in her book Tikim: Essays on Philippine Food and Culture (Anvil Publishing), she acknowledged as her teachers “those who give me information about food: market vendors, street sellers, cooks, chefs, waiters, restaurant and carinderia owners, farmers, tricycle drivers, gardeners, fishermen …” and on and on her list goes. In short, “everyone who eats and cares.”

Even at her most scholarly, her writing remained vibrant and readable. At the end of her narratives, she always had a glossary of food and food-related terms and list of publication sources. In one of her last books Palayok: Philippine Food Through Time, On Site, In the Pot (The Bookmark Inc.), a table of illustrations is included where the sources of each image is acknowledged.

Only she can come up with the just-right definition for that condition of a fruit, manibalang, i.e., “almost ripe, fruit soft yet firm and crunchy.” Or that piquant term for a young coconut’s meat, mala-uhog, i.e.., “literally, like snot.”

In Tikim, she also lays down some guidelines for credible food writing that read so elegantly like the writer’s character: “The writing done about food must be worthy of its subject. It should be not just utilitarian reportage, but writing that depends heavily on the unsaid, on the assumed, on the subtext of culture. It should require full participation from the reader, responses drawn from home and growing, from memory and pleasure. Because of this, it must be done with words that resound, and with the silence vibrating between and behind the words. Words that bear the culture within them need no adornments; they speak from intimacy of the experience. And yet, one reaches for words oft dedicated only to poetry, for words beyond the cooking stove, kitchen and plate, for words that convey sense, sensibility and sensuousness.”

Unknown to many readers, this “doyenne of food history in the Philippines,” a title given by renowned folklore scholar and museum professional Barbara-Krishenblatt-Gimblett, was a diabetic during all the time she was trying out restaurants, writing her food columns, researching Philippine town and sitios for almost-lost life and food ways. This never hampered her work. Her prose bristles with joie de vivre that is evident in her personal photos on exhibit.

Little known, too, is that the homemaker Doreen served her husband Wili, a top honcho in the interior design profession and himself a gourmet, take-out food. This writer once spotted her loading warm, freshly cooked laing in her car for her husband’s supper but not just from any run-of-the-mill source. She bought it from someone who cooked it with love.

The young bloggers have plenty to thank Fernandez for. This plenitude she made possible through her writings–cum-teachings. She foresaw the “new kind of interaction” where local and foreign chefs use Philippine ingredients in creative ways (mango-filled crepes, salmon belly sinigang) or how street food would continue to flourish in hard times and good.