Vuth LynoThoamada I, 2012

With zest and social media flair, Ties of History: Art in Southeast Asia, an exhibition of contemporary art in Southeast Asia, has opened with works of ten artists from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations member states.

In celebration of ASEAN’s50 years ofexistence, the exhibition is shown simultaneously in UP Diliman’s Vargas Museum, Metropolitan Museum of Manila, and Yuchengco Museum, Makati. The title is taken from a phrase in the ASEAN Declaration of 1967 that the ten member countries are bound together by “ties of history and culture.”

Curated by Patrick D. Flores, the three museums display a set of works from each artist, reflecting on their “process of artistic transformation and maturity…” They are Anusapati (Indonesia), Chris Chong Chan Fui (Malaysia), Roberto Feleo (Philippines), Yasmin Jaidin (Brunei), Min Thein Sung (Myanmar), Jedsada Tangtrakulwong (Thailand), Do Hoang Tuong (Vietnam), Savanhdary Vongpoothorn (Laos), and Vuth Lyno (Cambodia).

The exhibition includes paintings, sculptures, installations, photographs, videos, and mixed media works, with themes that touch on the environment and its destruction, migration, war, family and kinship, tradition and modernity, folk myths, social and gender issues, and everyday life.

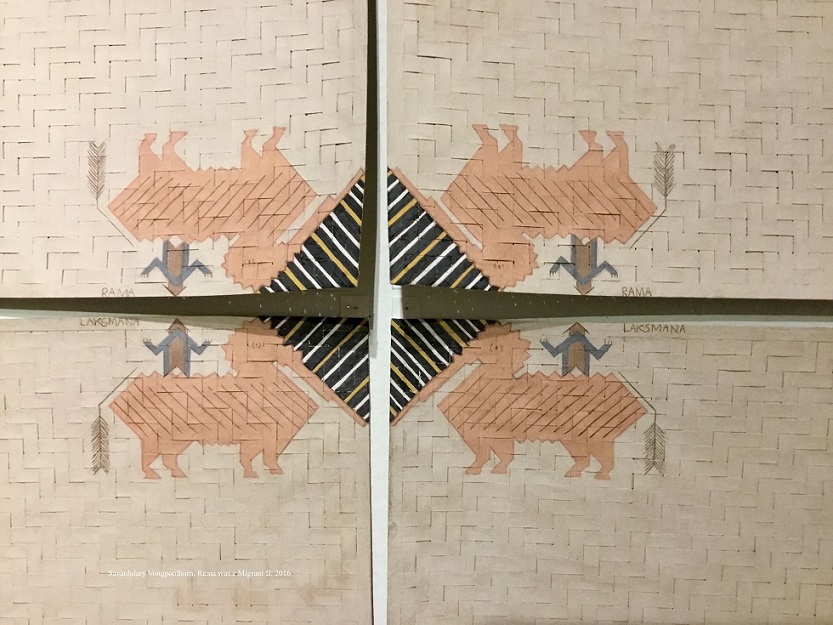

Savanhdary Rama was a Migrant II

The Artists

Savanhdary Vongpoothorn (b. 1971) uses rice paper and fabric scrolls to weave square mats, painted with swirls and curlicues in her Naga Cities II (2016). For Laotians, the Mekong River represents a life force and it is also the home of the river dragon, the naga that protects its nation. In Rama was a Migrant II (2016), she uses woven strips of mulberry bark paper, painted with the images of Rama and Lakshmana sitting on a flying horse, a reference to the Ramayana cycle of the Lao people. She learned how to weave with intricate patterns from a renowned Vietnamese bamboo craftsman, Uncle Muòi.

The works of Anusapati (b.1957) revolve on trees, and all its configurations. In his sculptures, Anusapati pays attention to the wood grain and texture of the bark. From a ceiling, he hangs seven sandalwood trees with its cut-off trunk, complete with all its intertwined fine roots, resembling the neural circuits of our brains.

In the same vein, Jedsada Tangtrakulwong (b. 1972) honors trees in his art-making. Having witnessed 16-year-old Indian Devil trees being cut down because of its strong odour, he made a multimedia installation, Downfall (2013), a 20-foot black metal sculpture that depicts the tree’s shadow when it was felled, a silent witness to man’s capriciousness. In an adjacent wall, 19 frames of black-and-white silhouettes of trees are on display as well as colored photographs of huge living trees in all its glory in Roi Et, Thailand. It brings to mind Joyce Kilmer’s line that “only God can make a tree.” Yes, and only humans kill and destroy them.

Min Thein Sung A Memory of Green 2012

Haunting images of men who look like apparitions— distorted, disappearing, and almost disintegrating right in front of our eyes —populate the paintings of Do Hoang Tuong (b. 1960). The works speak of an increasingly uprooted sense of self amidst rapid changes in society.

Vuth Lyno (b. 1982) raises some taboo issues in Cambodian society: the presence of mixed children, now in their mid-twenties, who were abandoned by their fathers, members of the United Nations Transitional Authorities in Cambodia in 1991-1992. In the name of “peace,” the Cambodian mothers and these children have suffered social violence and ostracism.

InThoamada I (2012) and Thoamada II (2016), Vuth presents an exploration of queer identity and sexuality and queer families’ notions of love and togetherness through photography. Thoamadais a Khmer expression that denotes “normal, natural, and habitual.” Vuth hopes that viewers would accept that such portraits are “common, like any other: they are all thoamada.”

Anusapati.Plantscape, 2018

Min Thein Sung (b. 1978) creates whimsical works drawn from daily life in Myanmar. In Memory of Green (2012), the artist captures childhood memories of pagoda festivals in a video installation; a wall of green pinwheels of various sizes in motioncomplete the work. In another installation, he recreates oversized toys as soft sculpture in coarse linen, such as a machine gun, horses, or elephants. It refers to the time when Myanmar was restricted from international trade. People then made handmade toys copied from foreign magazines for their children.

The seas and oceans may separate us but contemporary artists in Southeast Asia share a common trajectory of dreams and hopes, all aspiring for inclusive societies with dignity and a fair shot in life.

Ties of History runs until 6 October 2018.

Jedsada Downfall 2013