The turnout at the recent three-day Philippine Readers and Writers

Festival at The Raffles Makati was all the evidence needed to show

that the written word is alive, well and living in this country. It

can be said that published authors are the new rock stars as their

readers, mostly youngsters, lined up to have copies of their books

signed and took selfies.

Last week’s torrential rains delayed the start of the panel

discussions but did not cancel them. At the first one on “Weaving

Words Into Worlds: The Self and Space in Literature,” multi-awarded

author Cristina Pantoja Hidalgo, director of the University of Santo

Tomas Center for Creative Writing and Literary Studies and author of

more than 40 fiction and non-fiction books, looked back on how her

books, mostly written when she spent an expatriate’s life for 15

years, developed.

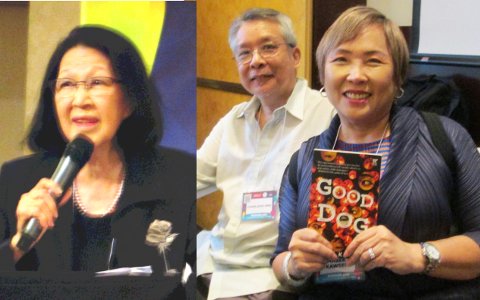

Cristina Pantoja Hidalgo

She said she used “the perspective of a Filipina looking backward

at her home.” Her earlier stories, written during the pre-martial

law period, were in the realist mode in her attempt to be relevant to

the times.

When she lived abroad with her family, her stories took on the form

of tales or modern fairy tales. “I used the fairy tale mode (in the

collections Tales for a Rainy Night and Where Only the Moon Rages),

but I didn’t know if they were good or bad.” Not until Gilda

Cordero Fernando told her they were excellent and deserved

publication.

Hidalgo said, “The tales were based on things that happened to me

and my friends but in fairy tale form. I wanted to tell a story that

I couldn’t tell if I used the realist mode. I didn’t want to be

found out. I’m a coward—that’s why I write tales.”

In the panel on “Writing the Novel,” Hidalgo suggested a way to

develop an idea for a story to the packed room: “Find something

interesting or compelling—a person, an experience, a place.”

She stressed the importance of reading, saying, “If you don’t

know what’s out there, the odds are not in your favor.”

She wrote with the influences of Henry James, Edith Wharton, Virginia

Woolf, Kerima Polotan, Cordero Fernando at the back of her head.

Later on, when she wrote her creative non-fiction (primarily travel

books), she credited women memoirists like Isak Dinesen and Maxine

Hong Kingston as her influences.

When Hidalgo started work on her novel Recuerdo, she said, “I

didn’t have to invent much because of our colorful family history

on my mother’s side.” This history included a secular priest in

their ancestry, a man who was part of the Revolution, exiled in the

Marianas Islands and executed in Bagumbayan.

She considered writer’s block as “kaartehan. I don’t believe in

inspiration either. You have to go out there and research, find out

what you need. I make writing my priority even if it means I absent

myself from work, I don’t check my students’ papers or I don’t

cook.”

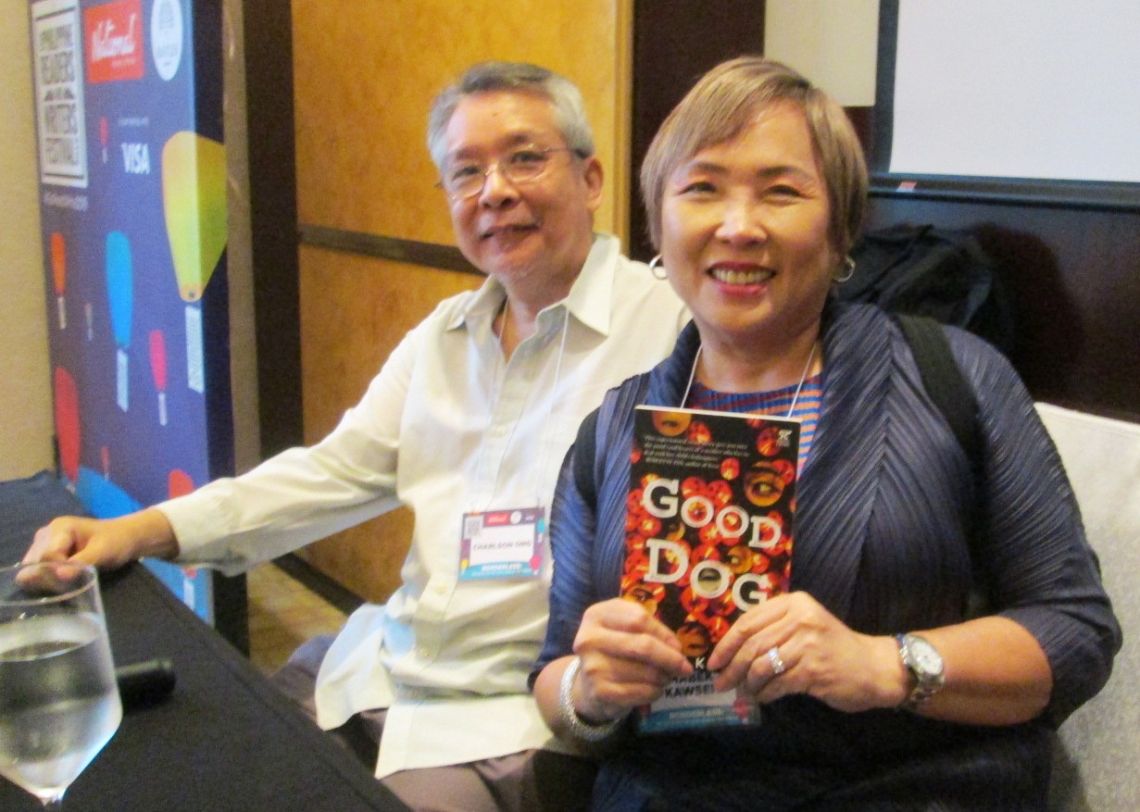

Charlson Ong, author of four collections of short fiction and three

novels, including An Embarrassment of Riches and Banyaga, considered

the writing of a novel as “a journey, a trek, a quest at the end of

the day.”

Charlson Ong and Mabek Kawsek

He said there are two ways to plot out a novel: to have a plan that

enables the writer to know where he or she is going and to have a

flexible outline. But he insisted on sticking to a plan “to give

you discipline, to avoid or stop you from going too far where you

want to go.”

His new novel, which had taken him 10 years to draft, opens with the

stampede of the masses watching Willie Revillame’s noontime TV

program “Wowowee.” When his mother died in February this year, he

decided to end a certain phase of his life that was slowing down the

writing.

He described his process as tending to allow the subconscious or his

dreams to serve as materials for his work. “Be prepared for the

long haul,” he advised. “If you don’t finish your novel in five

years, you won’t be able to although I broke my own rule when it

took me ten years to finish.”

Ong said the characters in a book are also “entwined with your

themes. They embody the discourses you are intending.” He quoted

National Artist Nick Joaquin who was once asked, “Who are you in

your book?” Joaquin answered, “No one and everyone!”

Ong said that to force oneself to write, “Invent your own Russian

winter.” He added, “Don’t get too close to people. Your best

friend or lover is your writing.”

Mabek Kawsek, whose debut crime novel Good Dog also tackles

Filipino-Chinese issues, came into being as a writer in 2006 during a

time when her generation of Fil-Chi women were still second-class

citizens in their households who never questioned the status quo and

tolerated abuse.

She said since China was closed after 1949, her grandparents were not

able to return there and, with her parents, assimilated with the

Filipinos. She suffered from a “cultural amnesia” about her

so-called country of origin. “I have no experience of China,” she

added. “I’ve watched Chinese movies with English subtitles. No

subtitles, no watching.”

She said her generation of writers owns a “hybrid voice” and have

“an infinite way of showing we have assimilated and gone beyond

assimilation.”#