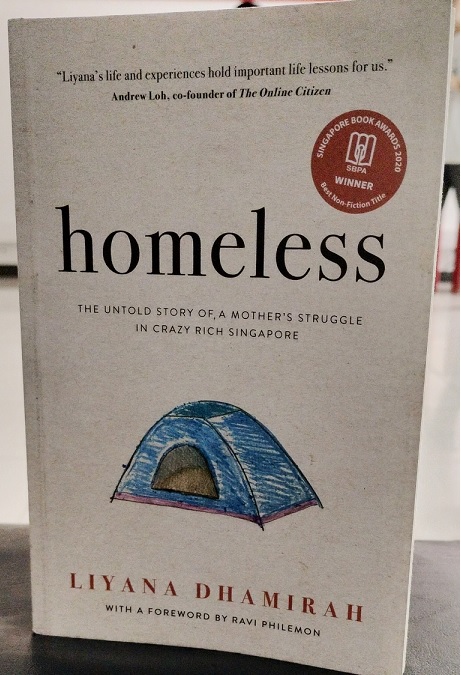

As difficult as it is to grasp the idea, there are homeless people in Singapore and Liyana Dhamirah was one of them. She was 12 years old when she lost her metaphorical home — her family — in 1999 with her parents’ announcement of their divorce shortly after the Ramadan festivities, she writes in “Homeless: the untold story of a mother’s struggle in crazy rich Singapore” (Epigram Books).

Dhamirah’s life was a game of dominoes. Next, she lost the flat they lived in, which her parents sold, and, later, the flat she, her mother, and siblings had moved into. When she was pregnant with her third child, she and her husband were unceremoniously booted out of her mother-in-law’s flat and ended up pitching camp indefinitely at a beach in Sembawang Park. (“Flat” is commonly used in Singapore in lieu of “apartment.”)

Dhamirah’s situation calls to mind the homeless Filipino families and overseas Filipino workers (OFWs). The former lose their homes to natural disasters, etc. while OFWs lose theirs to employment abroad, to which they resort for the family’s upkeep. The importance of a home and its absence are underscored in “Homeless…” Being homeless means being deprived of a congenial, secure environment and experiencing hopelessness.

Finding stability

Dhamirah wrote of missing the stability of a home, celebrating birthdays and holidays as she did in her childhood, and the regularity of work. She wanted an end to the uncertainty and the cold, damp climate of West Coast Park to where they moved from Sembawang Park to avoid arrest for their expired camp permit (it only lasts for a week).

Pregnant and tired with tent-living, she went to the then Ministry of Community Development, Youth, and Sports. Standing in front of the building, she recalls her feelings: “I prayed hard. I felt like screaming to release the tension and anxiety building up in me. I was desperate for the Almighty to hear my prayers. Desperate for a solution. Desperate for a way out. Desperate for the instability to end.”

OFWs go through taxing times abroad. Hailed as excellent workers, they’re actually solitary outsiders dealing with homesickness, racial/gender bias, and work stress. Behind the cheery social media posts, they’re looking for a home away from home in compatriots and strangers who, most of the time, are fair-weather friends.

Uneasy living

Dhamirah stayed with her aunt but, though grateful for being taken in, she found the setup impracticable because of the tight quarters and her aunt’s “razor-thin patience.” Her living arrangement changed when government help came through, but “home” was a living room in a three-room flat with two other families occupying the two bedrooms.

Privacy and freedom in movement are of paramount importance in a home. Dhamirah could only smile and accept the arrangement, which was better than a tent — or kariton (pushcart) in the Philippines — but it was still distressing. She and her family had no privacy; they huddled in the corner of the living room so others could get to their rooms, the kitchen, or the bathroom. They alternated in cooking in the tiny kitchen and bathed quickly so as not to keep the others waiting.

In the Philippines, homeless families make do with jerry-built “houses” on appropriated sidewalks. Abroad, OFWs lock horns even with potential landlords whose postings of their property-for-lease carry the caveat “Filipinos need not apply.” They put up with officious landlords who impose religious beliefs on tenants and who let themselves into the rented flat without prior notice. They suffer nosy neighbors questioning the legitimacy of their work status. They endure flatmates who steal their groceries and turn the flat into a pigsty or a motel.

World’s homeless

On the “Homeless by Country 2024” list, Singapore’s homeless population of 1, 036 is minuscule vis-à-vis some of its Asian neighbors: 2, 579, 000 in China; 1, 800 in Hong Kong; 122, 000 in Indonesia; 2, 700 in Thailand; and 4.5 million in the Philippines (worldpopulationreview.com).

In 2019, Singapore’s homeless was 1, 050. In 2021, the number dropped to 616, but the occupancy of temporary shelters increased from 65 to 420. Singaporeans become homeless because of family conflict, low wages, irregular work, landlord problems, and difficulties in securing and maintaining stable housing (lkyspp.nus.edu.sg).

The irony isn’t lost on Dhamirah who wrote, “Homelessness is a murky idea in many people’s minds. Poverty hides in the shadows as Singapore’s population grows for being ‘crazy rich’ — thanks to a certain book and Hollywood franchise, not to mention Singapore’s gleaming skyscrapers.”

Meanwhile, two-thirds of the Philippines’ 4.5 million homeless are found in Manila; of this number, 250, 000 are children living in streets, public spaces, and slum areas (www.ohchr.org). Filipinos become homeless because of low income, lack of job, domestic violence, and natural disasters (typhoons, earthquakes, and volcanic eruptions). The children are rendered homeless because of parental abuse, poverty, and sexual exploitation (bordenproject.org).

Extra assistance

Getting the homeless off the streets needs everyone on board. Dhamirah had government agencies to turn to but the bureaucracy kept her on interminable waiting lists. Her luck improved when Ravi Philemon and Andrew Loh from The Online Citizen (TOC) website interviewed her. She met them when they were handing out goodie bags and helpline numbers to the homeless at Sembawang Park.

Philemon helped expedite Dhamirah’s case by writing to the offices of Ministers K. Shanmugam and Vivian Balakrishnan, whose swift actions had Dhamirah moving from her tent and into the shared three-room flat on the first day of 2010. From then on, Dhamirah’s life improved. She started a business (she first sold handicraft and cake pops) and remarried, finding her second husband “a keeper and a good human being through and through.”

In 2017, Dhamirah, her children, and new husband moved into their own four-bedroom flat.

In the Philippines, the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) helps Manila’s homeless families with housing grants and funding for health and education through programs like the Modified Conditional Cash Transfer for Homeless Street Families. Another is ASMAE-Philippines that gives homeless children school support (bordenproject.org).

Stumbling block

Semantics helps or delays in giving the homeless assistance. Singapore clearly defines homelessness as rough sleepers, or those who sleep in public places, while the homeless are defined as those without access to adequate housing, but aren’t necessarily rough sleepers (todayonline.com).

There’s no encompassing definition of homeless in the Philippines, making it difficult for the effective provision of services. For example, laws on housing provisions for the urban poor lack straightforward definitions of a homeless person. On the other hand, the DSWD has categorized homeless people as families on the street, families of the street, homeless street families, and community-based street families (www.ohchr.org).

For OFWs, the solution to their homelessness is returning home, yet the assimilation isn’t easy. Like how Dhamirah felt living in that shared flat, OFWs have difficulty adjusting to the living conditions and especially the economics of being home. A common bugbear is that what may be simple abroad, like daily commuting, becomes a major problem, with passengers waiting for hours for a ride and, once getting it, are packed like sardines in public vehicles.

All hands on deck

Homeless Filipino families can match Dhamirah’s endurance, but they need her luck in meeting the likes of TOC journalist Philemon who contacted relevant government officials. Dhamirah was a constituent in Shanmugam’s district while Balakrishnan was in charge of community development then. (Philemon was once homeless, at 11 years old.)

The state of homelessness in the Philippines looks irreparable at a glance: street children everywhere, families pushing their kariton around the city, and OFWs pouring their misery in working abroad and being away from home in Threads.

Dhamirah’s happy ending is a strong testament to the effectiveness of the government and citizens conscientiously working together. The Philippines can do it, starting with setting a precise definition of homeless so assistance can be given accordingly and quickly. Equally important is fixing the economy in all earnestness so OFWs won’t have to leave their home to work abroad and so the mass unemployed can find work.

Losing one’s home is devastating because it’s where beliefs, dreams, and goals are nurtured. It’s the place one sets off from to expand one’s horizon and the safe place to return to when the world becomes too much to handle. It’s the place to breathe again.