Text and photos by ELIZABETH LOLARGA

A good number are, including illustrious names in the Philippine literary canon.

A good number are, including illustrious names in the Philippine literary canon.

In a controversial article in a magazine last year, Katrina Stuart Santiago wrote that the house of Philippine letters was on fire while the Filipino reader remained indifferent because the house’s masters continue the tradition of patronage by coddling younger writers who pander to their tastes and hogging powerful positions (e.g., peer reviews in publishing houses).

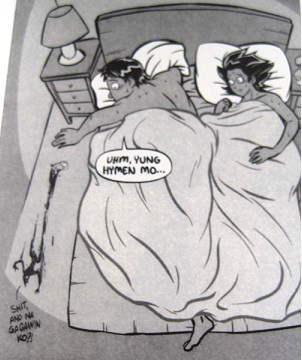

She gained notice for in-your-face views, her widely followed blog http://www.radikalchick.com/ and Of Love and Other Lemons (StuartSantiago Publishing and Boutique Books). She put together the collection of essays after a break-up when she found the distance and space to recover from a war that still leaves most women bearing the brunt of hurts. The book is illustrated richly, comically by hot graphic artists like Farley del Rosario and Mark Salvatus.

At her Mt Cloud Bookshop talk in Baguio, Stuart Santiago said the book “came from a personal history of love and loss and sadness, complete with the high – if not OA [over-acting] – drama of buckets of tears.” She wrote it over five years in different places where she felt safe: in Baguio, in neighborhood cafes in The Hague, among strangers in Amsterdam, at a friend’s pad in Switzerland and in Quezon where her ancestral home had a room she could stay in unnoticed.

She said, “Distance forced on me the realizations I needed to… close these chapters that I speak of in the book. Consider it me doing an accounting with the Universe, and saying: ‘Ok mamser, quits quits na tayo, ha? Puwede na’ko mag-reboot?’” She called the experience “being bigger than heartbreak.”

With a University of the Philippines Diliman background in literature, feminism and post-feminism, she wrote, “Love ain’t a fad. It’s not that we lose all sense when it comes to love, or that theory fails tremendously at explaining it. It’s that we must know this to be true: while we might have things to explain love by, these don’t always hold or stand up to its inexplicability. Because there is theory, and there is the lack of explanation for a man who is suddenly unable to speak; there is common sense, and there is utter lack of reason for love coming and sweeping you off your feet, or for it ending in utter confusion. We like to be able to explain the world, and this is what theories are for, but there are also some things one finds we should concede to because there are no words. Not for love. Or loss.”

With a University of the Philippines Diliman background in literature, feminism and post-feminism, she wrote, “Love ain’t a fad. It’s not that we lose all sense when it comes to love, or that theory fails tremendously at explaining it. It’s that we must know this to be true: while we might have things to explain love by, these don’t always hold or stand up to its inexplicability. Because there is theory, and there is the lack of explanation for a man who is suddenly unable to speak; there is common sense, and there is utter lack of reason for love coming and sweeping you off your feet, or for it ending in utter confusion. We like to be able to explain the world, and this is what theories are for, but there are also some things one finds we should concede to because there are no words. Not for love. Or loss.”

In her book, she called love an “ideological state apparatus” where the State and the Church conspire to keep women “in the dark ages of no divorce and no reproductive health bill.” She accused capitalism of fueling “the existence of a beauty industry that renders us all as objectified bodies,…that peg us to fixed and indestructible concepts of sex and consumption.”

She wrote that patriarchy and feudalism “have allowed women to think that where they are is the only space they can occupy, that who they’ve become is only allowed by the men in their lives, that they can be nothing if they are alone.”

She warned of “words we use against each other every day.”

Like describing a woman pokpok, malandi, maingay, parang lalaki. Also a casual greeting like ‘Bakit tumaba ka?’ instead of ‘Kumusta ka na?’

Like describing a woman pokpok, malandi, maingay, parang lalaki. Also a casual greeting like ‘Bakit tumaba ka?’ instead of ‘Kumusta ka na?’

“When we assert that some women ask for it because of what they wear, or that others just plain deserve what they get from men because they’re a particular kind of woman. When we say we are what we wear even as what needs to be said is that these bodies demand respect regardless of what hangs on it, or how it looks. When without thinking we talk about the good woman who waits/stays silent, and the bad woman who is opinionated/intelligent /independent, and say that they deserve what they get,” she added.

Her background includes a set of liberal parents. Mother Angela, author of Revolutionary Routes, is an activist. The daughter qualified, “She isn’t as aggressive as I am; she’s more of a hippie who knows how to listen.”

Although her views have made her a lightning rod for derogatory remarks in social media, she said, “Anything anonymous I ignore. Don’t diss me with 140 characters, make it 140 words naman! We can do many things ourselves. New, original writing will be praised in time.”

As a student, Stuart Santiago was one of five activists on campus along with then Philippine Collegian editor Ericson Acosta. Only five? She nodded, saying, “That led me to believe that we could do it even if we were few. Tapang (courage) is what I grew into.”