By CHERRY JOY VENILES

WITH almost four decades of sustained and large‐scale migration of Filipinos to foreign countries, the Philippines has emerged as one of the major migrant‐sending nations, next to China and India. But it has also fallen into the trap of calling every Filipino overseas an Overseas Filipino Worker or OFW, clouding the rich diversity of the overseas Filipino community.

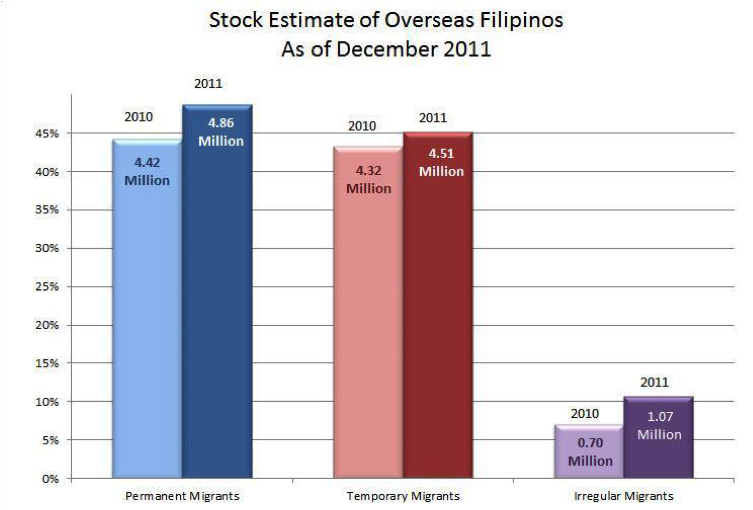

The stock estimate of overseas Filipinos computed annually by the Commission on Filipinos Overseas (CFO) shows 10.44 million Philippine-born Filipinos residing or working overseas in 2011.

But the aggregate, drawn from data of the CFO, Philippine Overseas Employment Administration and the Department of Foreign Affairs, shows permanent migrants outnumbering overseas workers, although by a small but significant margin.

In 2011, permanent migrants numbered 4.86 million or 47 percent of overseas Filipinos, followed by temporary migrants, including overseas workers, numbering 4.51 million or 43 percent. The stock estimate recorded 1.07 million or 10 percent as irregular migrants.

Who overseas Filipinos are

Who are permanent, temporary and irregular migrants who are collectively referred to overseas Filipinos or OFs?

Permanent migrants include immigrants, dual citizens or legal permanent residents abroad, whose stay does not depend on work contracts. All permanent visa holders or spouses and partners of foreign nationals are required to register at the CFO before their departure.

Temporary migrants, on the other hand, are those whose stay overseas is employment-related and who are expected to return to the Philippines at the end of their work contracts. Although most temporary migrants are OFWs, they also include students, trainees, entrepreneurs, businessmen and their accompanying dependents whose stay abroad is six months or more.

It is the job of the POEA and Overseas Workers Welfare Administration to regulate the recruitment industry for OFWs and provide necessary welfare support to returning OFWs, including those who are victims of recruitment violations, work-related accidents and other forms of emergency relief assistance.

Scholars under the exchange visitor program of the US government must register at the CFO prior to departure.

Filipinos who are not properly documented, without valid residence or work permits, or are overstaying in a foreign country—“TnTs” or “tago ng tago” in local parlance—count among the irregular migrants.

All together, they remitted $21.6 billion last year, according to the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas, and are a constant source of income for the Philippines.

Going beyond labor migration

The CFO stock estimate provides a good snapshot of the number of Filipinos overseas at any given time taking into consideration migrant flows.

This means that if 100 Filipino workers have completed their two-year contracts, and 150 others recently arrived on new contracts, while 10 others have overstayed their visas, the estimate would give a running number of Filipinos in a country at any given time.

But the tally also clearly shows that although the Philippines is internationally recognized for its vast and diverse human resources, providing more than 200 countries and territories worldwide with Filipino skills and talents, it has gone beyond labor migration.

Many leave the country other than for reasons of work. The reasons range from marriage migration to family reunification, from educational and business opportunities to professional advancement.

Permanent residents and dual citizens reserve the right to petition relatives in the Philippines. And with countries such as the US, Canada, Australia and most of Europe espousing the idea of family reunification, the number is expected to increase over time.

In countries such as Singapore and Saudi Arabia, skilled migrant workers have the option to bring along family members as part of the company’s remuneration package.

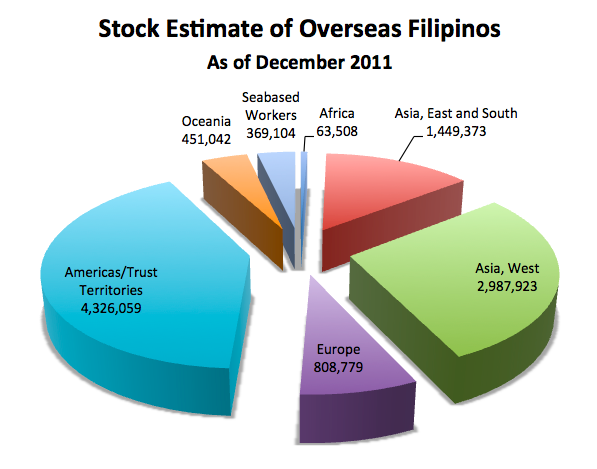

The top 10 destination countries of Filipinos are the US (33 percent), Saudi Arabia (15 percent), Canada (8 percent), United Arab Emirates (7 percent), Malaysia (5 percent), Australia (4 percent), Qatar (3 percent), Japan (2 percent), United Kingdom (2 percent) and Kuwait (2 percent).

An increasing number of OFWs from the Middle East have opted to apply for permanent skilled worker visas in countries such as Canada and Australia.

Japan’s policy on issuing visas to Nikkei-jins and their families has also contributed to the rising number of Filipinos in Japan despite the ban on the deployment of entertainers since 2005. Nikkeijin is a Japanese term for Japanese emigrants and their descendants who have established families and communities in recipient countries such as the Philippines.

Irregular migrants could be found mainly in the United States, Malaysia and Singapore. The large increase of irregular migrants in 2011 can be traced mainly to the 124 percent increase of irregular migrants in Malaysia, from 200,000 in 2010 to 447,590 in 2011, and the 67 percent increase in the US, from 156,000 in 2010 to 260,000 in 2011.

The number of Filipinos in Japan decreased by 69,476 or 24 percent mainly because of the natural calamities (earthquake and tsunami) which affected the country in March 2011. There was a 90 percent decrease in the number of Filipinos in Libya, from 27,349 to 2,724, and a 79 percent decrease of temporary migrants in Syria, from 13,869 to 2,890, mainly because of the Arab Spring.

Why the numbers matter

Understanding the stock estimate of overseas Filipinos gives a grasp of the realities of the program and policy environment the government and the private sector need to focus on in the interim.

If the DFA has closed down 11 consulates abroad, do the numbers justify the closing? If an Algeria attack Part 2 looms, is the government prepared to bring out all the OFWs there? If the European economic crisis continues for years, how many Filipinos and their families would be affected? If the government cannot get a consistently high voter registration and turnout for overseas absentee voting, can it map out in which areas it has succeeded in getting OFs to vote? If Malaysia has such staggering numbers for irregular migrants, what is the government doing?

And, more important, service providers such as remittance companies and banks and even local government units should certainly look at the numbers and say, “If 100,000 OFWs in Saudi are returning home after a two-year contract, what could we possibly offer them to make them stay in the Philippines?”

Whether immigrants, OFWs, TNTs or OFs, the numbers matter because they are, in the end, Filipino wherever they may be in the world.

(Cherry Joy Veniles has more than 10 years experience in Filipino migration and is the outgoing head of the Policy Planning and Research Division of the Commission on Filipinos Overseas.)