By JOSEPH CORTES

AN epic tells the aspirations of a people: where they come from, what they are, and what they hope to be. At times of hardship and despair, retelling the people’s glorious past in the form of an epic, and not its history, serves to rally the masses to gather together and work on their destinies.

AN epic tells the aspirations of a people: where they come from, what they are, and what they hope to be. At times of hardship and despair, retelling the people’s glorious past in the form of an epic, and not its history, serves to rally the masses to gather together and work on their destinies.

In the Philippines, epics have slowly disappeared from the national consciousness. It is not taught in schools; rather, it is passed on by word of mouth from elders, but only if they still have time to recount these stories to their young ones. Today’s modern times have substituted the Internet for the tradition of storytelling, when children gathered around the campfire or dinner table as their elders tell them of their people’s glorious past.

This is one reason why the people of Albay, and particularly Legazpi City, should be commended for continuing with this tradition of storytelling with its annual Ibalong Festival. The festival commemorates a glorious past that would have been forgotten now had not Legazpeños and Albayanons taken the initiative to remember it.

The Ibalong is one of the epics of the Philippines. What is known about it comes from a fragment of 60 stanzas from the original 400 that was transcribed by Spanish friars from the oral tradition of the people of Bicol. There are doubts as to its authenticity, but the Bicolanos have embraced the epic as a source of their indigenous identity.

The Ibalong fragment tells of how the hero Handiong conquered the land of Ibalon from the creatures of the wild and transformed it into the Bicol that we now know. He is the figurative father of the Bicolanos.

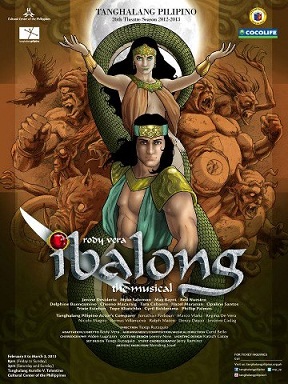

Presently being staged by Tanghalang Pilipino at the Cultural Center of the Philippines is a musical production based on the Ibalong epic. Playwright Rody Vera has taken liberties with the epic’s narrative to fashion a tale that would be worth an evening’s performance. Set to music by Carol Bello under the direction of Tuxqs Rutaquio, the musical gives an idea of the glorious past of the Bicolanos, as well as serving as a showcase for its lead, the dazzling Jenine Desiderio.

Vera has refashioned the Ibalong from the point of view of Oryol (Desiderio), the snake woman who is the daughter of Asuwang (Jonathan Tadion), the god of the underworld. Oryol is witness to man’s subjugation of the land of Ibalon, from the short-lived rule of Baltog (Nicolo Magno), who came to mine the mountains of its gold, to the vast colonization instituted by Handiong (Myke Salomon). To rescue the Sarimaos, the creatures of the wild, from Handiong’s destruction, Oryol seals a pact with the Bicolano hero: she cuts off her tail and marries him, as she gives Handiong the means to domesticate the creatures to ensure their survival. When Handiong aspires to subdue even the gods, who are led by Gugurang (May Bayot), the goddess of the heavens, he finally meets his match. When his son Makusog (Cheeno Macaraig) is hit by lightning and dies as he tries to reach the heavens, Handiong gives up his life in exchange for his son’s.

Vera has refashioned the Ibalong from the point of view of Oryol (Desiderio), the snake woman who is the daughter of Asuwang (Jonathan Tadion), the god of the underworld. Oryol is witness to man’s subjugation of the land of Ibalon, from the short-lived rule of Baltog (Nicolo Magno), who came to mine the mountains of its gold, to the vast colonization instituted by Handiong (Myke Salomon). To rescue the Sarimaos, the creatures of the wild, from Handiong’s destruction, Oryol seals a pact with the Bicolano hero: she cuts off her tail and marries him, as she gives Handiong the means to domesticate the creatures to ensure their survival. When Handiong aspires to subdue even the gods, who are led by Gugurang (May Bayot), the goddess of the heavens, he finally meets his match. When his son Makusog (Cheeno Macaraig) is hit by lightning and dies as he tries to reach the heavens, Handiong gives up his life in exchange for his son’s.

The Ibalong speaks of how heroes brought order and civilization to what was considered wild, but at what cost? In claiming Ibalon, Handiong virtually destroyed the land and the creatures that lived there. The forests slowly disappeared as settlements took over. What could have been a peaceful coexistence between Handiong’s people and the Sarimaos became a campaign to conquer nature. It was when the Bicolano hero was confronted by his place in the world, that he was after all just a man, that he finally redeemed himself from wanting to conquer the whole of nature. More than the life of a hero, “Rody Vera’s Ibalong” is more a cautionary tale as to the need for balance between man and nature. In the end, if man continues to upset this equilibrium, he only has himself to blame.

The strength of this musical rests mainly on the actor playing the role of Oryol. As the story’s narrator, she must carry the narrative through its course, bringing the audience into the world of Ibalon. Jenine Desiderio, a “Miss Saigon” alumna, brought not just her singing skills but her charms as well in delineating the serpent woman. Aided by two puppeteers who carried her long tail on stage, she slithered her way through much of the musical: at times, guileless, for she never saw man until Baltog invaded the forests of Ibalong; at times, alluring, as she teased Handiong into submission; at times, sorrowful, as when Handiong’s men captured the Sarimaos and declawed and defanged them to submission. Yet she was also pure woman, especially when she gave birth to Makusog, her son with Handiong. The character of Oryol is a tough one, because she is on stage most of the times. The range of emotions required from the actress playing her runs the gamut of expression, and she does most of this while singing. This musical is blessed to have Desiderio in its cast.

Kudos also goes to Salomon, a Handiong worthy of Desiderio’s Oryol; Macaraig in the dual role of Makusog and the Young Handiong, quick with his swordplay and secure in his singing; and Bayot as Gugurang, with the tricky writing of her solo in Act 3. TP has gathered together a versatile ensemble that sang, danced and acted all at the same time. Aided by the fantastic costumes by Leeroy New and the choreography of Alden Lugnasin, the cast had no difficulty drawing in the audience in enjoying this musical. Bello’s music was a bit spotty, as she mixed musical genres to give the different characters their chance to shine. It is when she adopted a neo-ethnic attitude that her music worked best and enchanted. Rutaquio ably gathered together all these disparate elements and provides an entertaining almost-three hour show.

(“Ibalong” will have performances at the CCP Little Theater on Feb. 15, 22 and March 1 at 8 p.m.; Feb. 9, 16, 23 and March 2 at 3 and 8 p.m.; and on Feb. 10, 17, 24 and March 3 at 3 p.m. )