In a speech in Abra six years ago, then-vice presidential candidate Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr. vowed that he would not follow in the footsteps of his father, the late dictator Ferdinand E. Marcos.

Now that he has been elected as the country’s 17th president, Marcos Jr. appears to be not stepping out of the shadow of his strongman father and namesake, based on some of his appointments and policies.

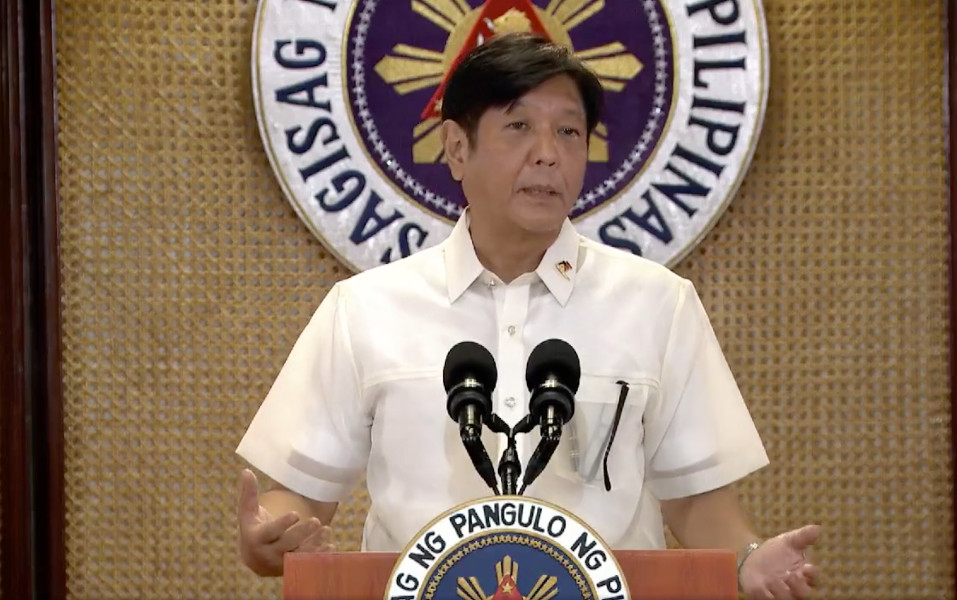

When he delivers his first State of the Nation Address (SONA) in today’s joint session of Congress, Marcos Jr. is expected to spell out his plans and programs and enumerate legislative measures he wants Congress to pass.

From his SONA, we can get a glimpse of how Marcos Jr. will be similar or different in the way his father ruled the country for 20 years, from 1965 until his ouster in February 1986.

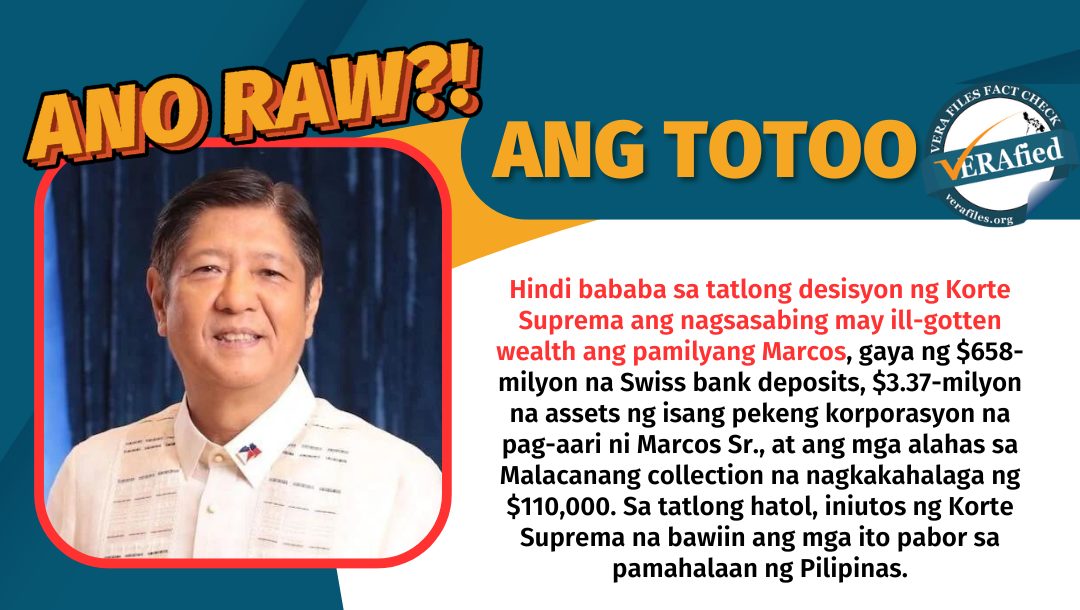

The elder Marcos presided over an economy that grew during the beginning of his 20-year rule but placed the country under martial law in September 1972, just a few months before his two-term limit as president should have ended. He abolished Congress and ruled by issuing presidential decrees, curtailed press freedom and other civil liberties, and ordered the arrest of opposition leaders and militant activists. When the Marcoses were flown to Hawaii in 1986, they left behind an economy in shambles, deep in debt. The Philippine debt ballooned from $600 million in 1965 to $26 billion in 1986, a 4,300-percent increase.

On the other hand, Marcos Jr. has inherited an economy recovering from the onslaught of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, which necessitated a strict lockdown that forced many businesses to close down. His predecessor has left behind an outstanding debt of P12.76 trillion as of April.

On the day the younger Marcos took his oath as president, the peso hit a 17-year low of P55 to the US dollar. The next day, the Bangko Sentral said the June inflation could hit 6.5 percent, way above the government target of 2 to 4 percent for 2022.

Prices of consumer goods have been rising as prices of petroleum products fluctuate, largely as a result of the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine. According to the Department of Energy, local prices of gasoline and diesel have increased by P19.30 and P34.80 per liter, respectively, as of July 19, since January.

These are just some of the problems the new president is expected to address in his first SONA today. What will he do to lower fuel prices, which should create a domino effect on the prices of consumer goods? Can he really bring down the price of rice to P20 per kilogram, as he promised during the election campaign?

News reports say Marcos Jr. is left with too little money to spend for the second half of 2022 because his predecessor had already released 93.2 percent, or P4.68 trillion, of the P5.02 trillion national government outlay for the entire year.

When the elder Marcos delivered his first SONA in January 1966, he said the country was also “in a state of crisis,” citing a government with a huge budget deficit and heavily in debt.

The father and the son similarly raised primary concern to strengthen the agricultural sector, highlighting the need to attain self-sufficiency in food production, especially rice. The son went further by assuming control over the Department of Agriculture, which his father created as a separate line agency from the Department of Agriculture and Natural Resources in 1974.

Will Marcos Jr. revive his father’s Masagana 99 program envisioned to increase rice production? The program was, however, declared a failure after the presidency of the elder Marcos because the supervised credit scheme it offered to farmers became unsustainable.

In a Senate hearing in May 2020, the then-Finance secretary, Carlos Dominguez III, debunked the claim of Sen. Imee Marcos that Masagana 99, which she described as one of her father’s pet projects, had been effective and successful. Dominguez, who was Agriculture secretary from 1987 to 1989 under Cory Aquino, said 800 rural banks went bankrupt because of Masagana 99, which was launched in 1973, offering highly subsidized loans to farmers so they could buy fertilizers and invest in farm equipment.

The Marcoses have their own version of stories, not only about Masagana 99 but also on many other things about the past involving Marcos Sr. and his administration, particularly during the martial law years, from 1972 to 1981, as well as his ouster in 1986.

In his inaugural address on June 30, Marcos Jr. promised to draw up a “comprehensive, all-inclusive plan for economic transformation.” One of the priorities he mentioned was agriculture. “The role of agriculture cries for the urgent attention that its neglect and misdirection now demand. Food self-sufficiency has been the key promise of every administration. None but one delivered. There were inherent defects in the old ways and in recent ways, too,” he said.

If, in his mind, only his father succeeded in attaining food self-sufficiency, it becomes obvious that Marcos Jr. assumed the agriculture secretaryship to bring back the programs, such as the Masagana 99, that the late dictator introduced, even if those made the intended beneficiaries poorer. Here we go again!

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.

This column also appeared in The Manila Times.