MANILA – In late August 2018, a video clip showing seven men, in their early twenties, smoking weed made the rounds of Philippine social media.

It went viral, but not so much because smoking cannabis is illegal under the country’s Dangerous Drugs Act. What propelled its spread through social media was how men puffing on weed were openly taunting President Rodrigo Duterte, known for his tough crackdown on illegal drugs in this Southeast Asian country of some 105 million people.

Since 2016, the Duterte government has been waging a bloody war on drugs that, by the police’s own estimates, has killed over 4,800 people as of Aug. 31 this year. The young men filmed in the video clip did not seem to care. So brazen, or so stoned, they were seen laughing at one point and calling for marijuana legalization.

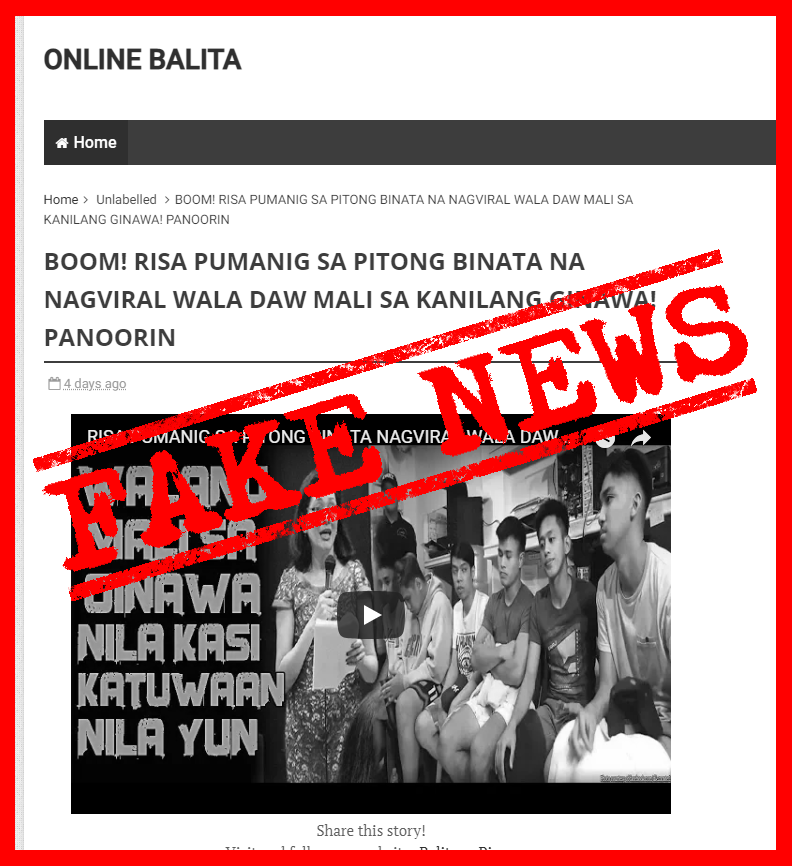

Days after the video was posted on Facebook, a web page calling itself Online Balita (Online News) published a fake report whose screaming headline claimed that an opposition senator, Ana Theresa ‘Risa’ Hontiveros, had defended the seven cannabis users and said they did nothing wrong.

The fake report also urged social media users, in all capital letters, to watch the supposed proof themselves in a Youtube video clip. Upon checking however, this clip did not bear out Hontiveros’ supposed remarks. Instead, it contained a tampered thumbnail that had crudely stitched together separate images of Hontiveros and the young men, and added a fake quote card to boot.

Subsequently, a network of Facebook pages shared the fake Hontiveros report and made it viral, riding on the wave of public emotion stirred by the real video clip of the weed users, analytics from the online tool CrowdTangle show.

This example captures how online disinformation in the Philippines is – distilled.

Its backdrop is the Philippines’ heated political landscape – and the deep, often emotional and angry divisions between those who support President Duterte and those who have been against him since he won the 2016 presidential election.

‘Patient zero’ of the modern disinformation era

In truth, the war on the online front has played a major role in the story of Duterte’s rise to power. In fact, the 73-year-old leader has been dubbed “patient zero” of the modern disinformation era.

“Before the world learned of Cambridge Analytica and Russian trolls (to skew public sentiment), there was Rodrigo Duterte’s presidential campaign in the Philippines,” Jonathan Corpus Ong of the University of Massachusetts Amherst wrote in an August article for AsiaGlobalOnline.

The President, Ong says, benefited from a savvy social media campaign “that many now regard as a harbinger of the tactics and phenomena that later came to global attention.”

Online disinformation in the Philippines, particularly its use in partisan political activity, only grew sharply after 2016. Indeed, Filipinos’ preference for Facebook is reflected in the fact that country has some 67 million active users of the social media platform. That makes Filipinos the 6th largest group of Facebook users in the world, according to the Global Digital Report 2018 produced by the London-based We Are Social marketing group.

An analysis of fake news reports identified and documented by VERA Files Fact Check, a fact-checking project run by the online non-profit media organization VERA Files, shows that for a good portion of 2018, deceptive content after deceptive content emerge in very similar ways across social media.

They are almost always explicitly political, almost always attack critics of the Duterte administration or promote or support the President or his policies, VERA Files Fact Check’s analysis of fake news reports shows.

They almost always rely on deception strategies that are crude in execution but are effective in stirring up strong emotions that reinforce deep-rooted biases. For example, the fake news item on Hontiveros was popular among groups already critical of the senator and supportive of Duterte.

VERA Files Fact Check identified and debunked 193 online posts over the period April to October 2018, after the organization became part of Facebook’s third-party fact-checking program.

Certified by the International Fact-Checking Network in the US-based Poynter Institute, VERA Files is one of Facebook’s three fact-checking partners in the Philippines. Facebook has been tying up with fact-checking groups and media organizations in some 24 countries to boost capacity to combat disinformation online.

For sure, there were more than 193 deceptive posts online within the six-month period mentioned, but the items that VERA Files debunked covered most, if not all, of the most viral and have reached the most number of online users.

The patterns that VERA Files identified from these posts provide a robust portrait of online disinformation in the Philippines.

Online disinformation is overwhelmingly political

Online disinformation is overwhelmingly political: eight in 10 deceptive posts are about political issues or figures, while the motivations for the rest are either purely economic or unclear. Moreover, six in 10 attack specific individuals or groups, almost always those critical of the Duterte administration.

In the set of posts debunked by VERA Files Fact Check, Vice President Maria Leonor ‘Leni’ Robredo, a member of the opposition Liberal Party who has at times been critical of the President, as well as a subject of Duterte’s barbs, is the most common subject of negative coverage by at least 27 fake, false or misleading reports. Hontiveros follows with 14.

Robredo says she is not surprised. “We have been dealing with attacks against me and my office since the start of my term,” she told VERA Files in an email message. “This is nothing new and in fact, after more than two years, it is almost funny to think about how much has been invested in such misinformation campaigns, with nothing to show for their ‘success,’” the Vice President added.

For her part, Hontiveros says the casualties of fake news are not just their targets but truth itself. “It is unfortunate that social media has been so heavily weaponized,” she pointed out. “It is a hard enough job to make sense of all the information available to us online even without people trying to feed us false information.”

“It is one thing to commit occasional errors of fact, and quite another to deliberately mislead the public for the sake of an agenda,” Hontiveros added. “We’ve seen this in the proliferation of hate speech, violent online rhetoric, and it its most extreme form, potential interference in elections.”

Duterte reaps political benefits from disinformation

Administration officials, including the president himself, have not been immune from being targets of disinformation narratives.

In September, a website called Taxial posted a misleading story claiming state auditors were alarmed by the Duterte administration’s “keeping” huge chunk of foreign assistance funds. The story, playing up on the ambiguity of the word ‘keeping’ in this context, twisted a genuine report produced by GMA News Online, which contained no such claim.

Earlier in June, former police chief Ronald Dela Rosa figured in a hoax report about a purported sex video of him and his supposed mistress.

Private companies like Nestle and Globe have been targeted by disinformation too, the motive appearing to be economic more than political, in the race to get the most numbers of users to click on such reports and be bombarded with online advertisements.

But these types of disinformation lag far behind those that aim to generate support, defend or promote Duterte himself or his policies. More than any political figure, he is the one who reaps political ‘benefits’ from items of disinformation.

The common ‘story lines’ of fake reports that circulate in social media feature variations of fabricated reports such as those that say Duterte has been named best president in the world or the universe, or that some high-profile celebrity like American actress Angelina Jolie has praised him and his government’s policies.

Former senator Ferdinand ‘Bongbong’ Marcos Jr. and his father, the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos, come after Duterte in the list of political personalities who are the most popular beneficiaries of online disinformation.

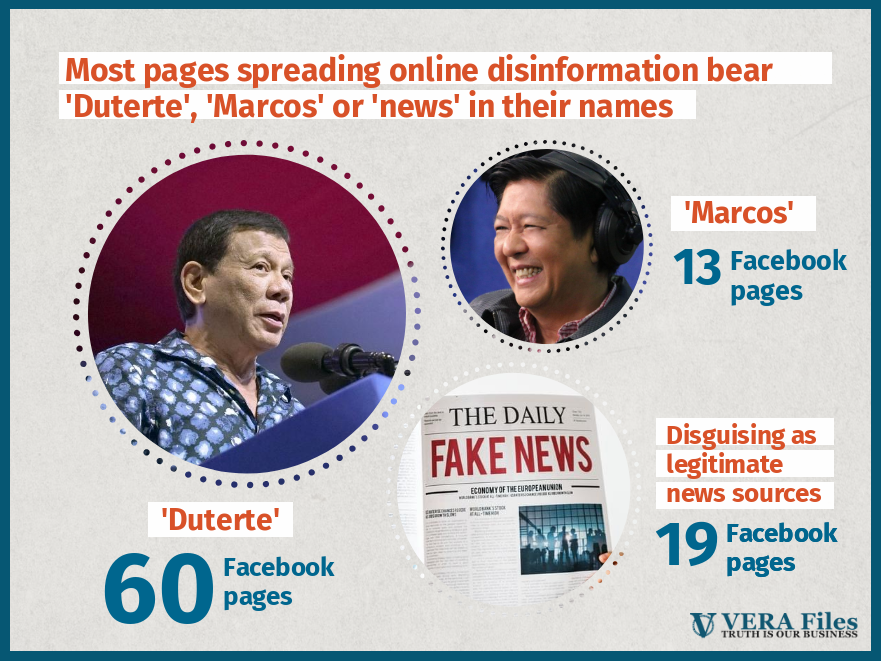

But there is much more to the Duterte and Marcos links to disinformation than how favorable the content of online disinformation is to them, or antagonistic to their critics. Online disinformation spreads through a network of interrelated web and mostly Facebook pages, the latter generating traffic to the former.

These pages have two prominent and sometimes interlocking features: they either bear the names of Duterte or Marcos, or purport to be legitimate sources of news by using words like “media” or other synonyms for “news” or its Filipino equivalent ‘balita’

Marcos Jr. did not respond to interview requests by Vera Files for this story.

‘They should be indignant that their names are being dragged’

The matter of the President’s name appearing in online pages that spread disinformation came up during an October 2017 hearing by a Senate committee on a bill seeking to penalize “fake news.”

While he called fake news “troublesome,” presidential communications undersecretary Joel Sy Egco denied the Presidential Palace’s involvement in their production and distribution. It is easy to put up a web page and name it after anyone and then when caught, take it down and put up another, he told the committee.

In October, Facebook announced that it has taken down 95 pages and 39 accounts in the Philippines for violating spam and authenticity policies of the social media platform.

Facebook did not provide the full list of the banned pages and accounts but mentioned the web pages that routinely carried the name of the President, including Duterte Media, Duterte sa Pagbabago BUKAS, DDS, Duterte Phenomenon and DU30 Trending News. Some 4.8 million Facebook users followed at least one of the pages taken down, the company added.

When a spokesman for the President, Salvador Panelo, was asked in a media briefing if this reflected the kind of supporters Duterte has, he replied: “Not necessarily.”

“Facebook must have its rules and regulations. If they are implementing that, then that’s their own rule,” Panelo said.

“If the concern is there will be no more avenues (for the President’s supporters on social media), there are so many avenues,” Panelo added. “We have Twitter, Instagram and many others where advocates can express themselves in support of this administration.”

Hontiveros was forthright in her response when asked about pages spreading disinformation that were found to carry the names of either Duterte or Marcos.

“We should not forget that one of the things that President Duterte and Ferdinand Marcos have in common is the propensity to lie,” she said. “The late dictator faked his persona as a war hero and now Bongbong Marcos and former Senator (Juan Ponce) Enrile are trying to revise history by lying about the atrocities of martial law, and their very own involvement in this horrific period of our past,” Hontiveros added.

Enrile, who is seeking another term as senator in the May 2019 election, was defense minister during the Marcos regime and became one of the leaders of the ‘People Power’ civilian revolt that led to Marcos’ ouster from power in 1986.

Robredo, who beat Marcos Jr. in the 2016 vice presidential race but faces an election protest from him, says it is dangerous that Duterte and Marcos supporters are easily convinced by disinformation – “and even more insidious if these supporters turn out to be the actual sources of them.”

“The President and Mr. Marcos should call out such pages and groups,” Robredo said. “If they stand for the truth, they should be indignant that their names are being dragged into misinformation campaigns which seek to mislead the Filipino people.”

Fake, false, misleading

Some deception strategies are preferred over others, and the purveyors of online disinformation have repeatedly relied on three broad techniques: plainly faking information, misleading readers and making false claims.

On its face, making distinctions among these three methods might seem like a misguided, if not futile, exercise; they are all “fake news” after all. Yet distinctions could prove useful in debunking disinformation and in informing online users about its nefarious effects.

A branch of psychological research called inoculation theory, which borrows from the logic of vaccination, has it that what neutralizes the effects of disinformation goes far beyond simply clarifying how one claim is erroneous, and needs to involve an explanation of the deception techniques and strategies behind the false item.

“Beyond misinforming people, misinformation has a more insidious and dangerous influence,” wrote John Cook, a research assistant professor at the US-based George Mason University, in an article for the website The Conversation.

When people are only presented with facts and “fake news” side by side, Cook notes, the pieces of information cancel each other out and people do not change their beliefs. “There’s a burst of heat followed by nothing. This reveals the subtle way that misinformation does damage. It doesn’t just misinform. It stops people believing in facts,” he added.

What does shield people from the effects of misinformation is exposing them to small doses of misinformation, much like vaccines.

“Throwing more science at people isn’t the full answer to science denial,” Cook wrote. “It turns out the key to stopping science denial is to expose people to just a little bit of science denial.”

The distinctions between fake, false and misleading reports could be seen as ranges in degrees of being factual, across a spectrum of sorts.

The fake story about Sen. Hontiveros defending the young men smoking weed is an outright fakery. Among the three types of fake news, it is farthest from verifiable fact: the video thumbnail was fabricated using an editing software, the supposed quote was fabricated, and no legitimate media outfit reported that the senator had defended the seven young men.

Reports that make false claims fall somewhere in the middle and compared with fakes, are more closely-linked to some real event, albeit still not supported by facts.

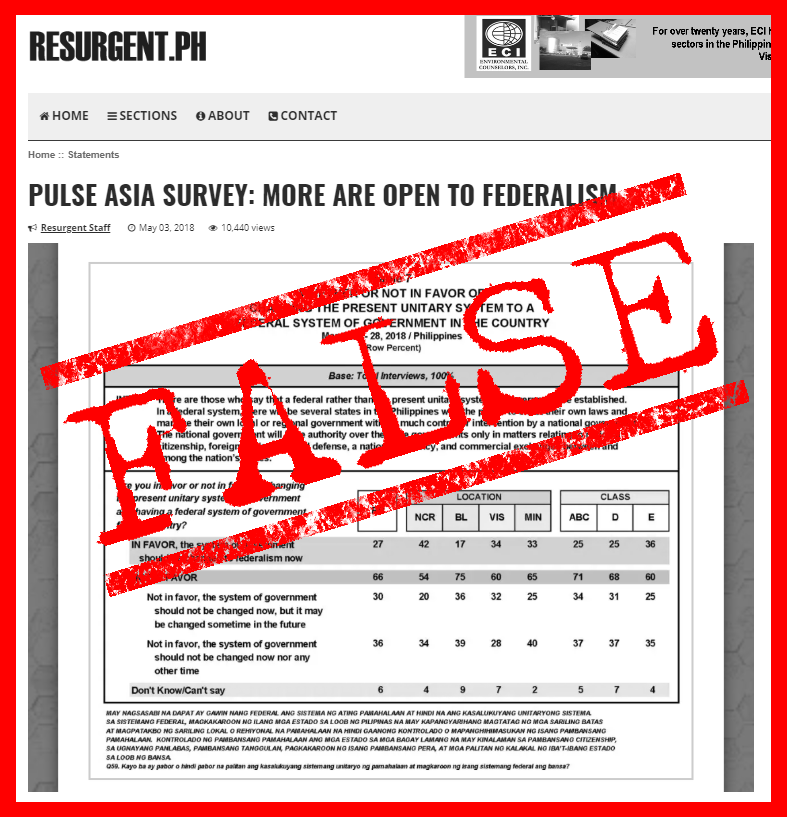

In May, a website called RESURGENT PH, right around the time the issue of amending the Philippines’ government structure was big news, falsely claimed that a survey by Pulse Asia, an independent polling agency, showed more Filipinos being open to federalism.

To support its claim, the website manipulated survey numbers by adding the figures of those in favor of federalism to those opposed but said they might be open to change some time in the future.

This conflicts with Pulse Asia’s own analysis of its survey data, saying that this shows the prevailing public sentiment to be “one of opposition to replacing the present unitary system of government with a federal one.”

The false report could have reached 14.9 million people on social media, Crowd Tangle analytics show, with the web traffic generated by known pro-Duterte Facebook personalities Thinking Pinoy, For the Motherland – Sass Rogando Sasot and Mocha Uson Blog.

The last pro-Duterte online space is run by former presidential communications assistant secretary Margaux Esther ‘Mocha’ Uson, who resigned from this post in October in preparation for seeking a party-list seat in the next year’s election for House of Representatives.

Misleading reports move closer to the facts, their twists and manipulations being subtler than fakes and false claims.

In June, a website called TRENDING TOPICS TODAY misled readers by publishing a story claiming that plunder charges had been filed against former president Benigno Aquino III and several other government officials for supposedly shipping gold bars worth billions of dollars to Thailand.

The plunder case indeed existed, but was filed more than a year ago, something the misleading report conveniently left out. Moreover, the case was already determined to have been based on a document that the Central Bank of the Philippines called “spurious.”

Fixing the user pool through media literacy

These deception strategies are not mutually exclusive, and have been used in various combinations by the creators of disinformation campaigns.

Knowing these categories help professional fact-checkers inoculate readers from disinformation by exposing them to disinformation techniques. Beyond this, they help readers develop fact-checking skills on their own.

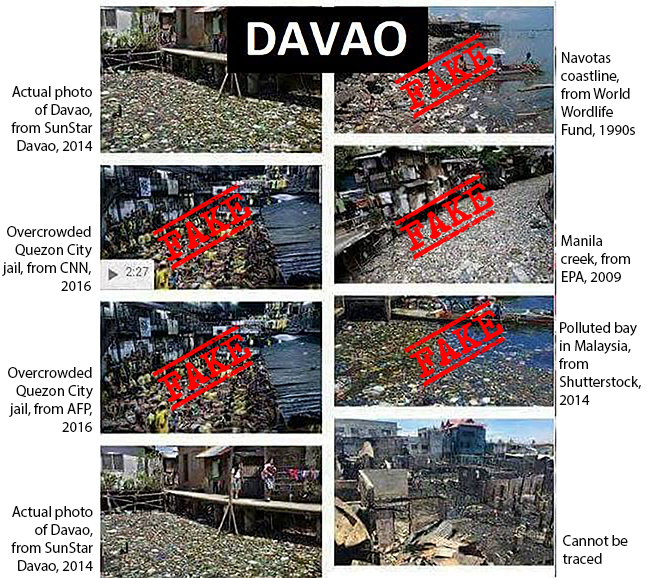

For instance, online users who want to find out if a photo on their social media feed is fake, or if a video thumbnail has been manipulated, need to use methods like reverse image searching. Those who suspect that they have come across false online news or are being misled need to verify these by going to, and reviewing, primary sources of information.

Equipping users with these skills is crucial in the fight against disinformation, says Ming Kuok Lim, advisor for communication and information at the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) office in Jakarta.

“Things like how to verify if a photo is real, how to verify if this information was published, when it’s purportedly published, techniques to check whether the metadata matches the actual date, Google reverse search, and learning to be critical between and reading between the lines” have become basic skills for using the internet and social media, Lim said in an interview.

“We can fix the user pool through more literacy education,” he added.

In September, UNESCO published a handbook for journalism education and training to address online disinformation.

Online videos most popular sources of disinformation

In particular, the ability to verify the authenticity of videos would seem to be an important, if not necessary, skill, as more than half of disinformation that made the rounds online from April to October 2018 are in the said format.

The methods used to tamper with videos range from sophisticated to very crude, VERA Files’ analysis shows.

Some posts contain clips that purport to be actual news reports, feigning credibility by carrying news logos and featuring computer-generated voice narrators.

Others rely on clickbait headlines that claim something explosive or important could be found if a user watches the corresponding video, and then roll out unedited hour-long clips or crudely spliced ones that do not bear these claims out.

These clips often feature people ranting against one political issue or another. One recurring personality of this type is a Duterte supporter called Dante Maravillas, who claims to be a reporter for, and owner of, Tarabangan Albay News Television.

Maravillas frequently posts videos of himself commenting on current political issues, and his views have repeatedly been twisted and taken to be factual by false reports, or are spliced with other clips.

Maravillas also appears to be a favorite source used by a YouTube channel called TOKHANG TV, which takes its name from the vernacular code for the Philippine National Police campaign against illegal drugs.

TOKHANG TV videos in turn appear to be a popular source of material for many websites sharing deceptive content. In fact, they were used in more than 20 fake, false or misleading posts over the April to October 2018 period that Vera Files’ analysis covered.

The popularity of YouTube videos in the manufacturing of online disinformation is not a surprise.

After videos that are uploaded on Youtube, the second most popular source of material used in disinformation are manipulated reports from no less than mainstream media in the Philippines.

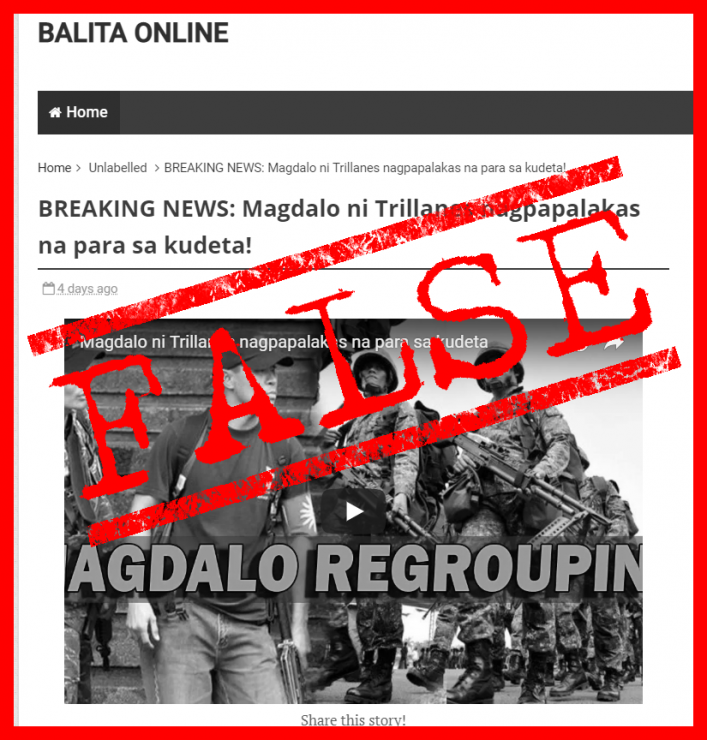

In September, the website Balita Online (News Online) published a false story claiming that the Magdalo group of soldiers led by Sen. Antonio Trillanes IV, which had staged mutinies in 2003 and 2007, was preparing for another coup.

The post carried a 10-minute clip, which was lifted from an almost two-hour Facebook Live video clip by Duterte promoter Maravillas, but provided no support to the claim against the supposed coup plotters. The video thumbnail was manipulated, splicing old photos from the foreign wire agencies Associated Press and Agence France-Presse.

Some 1.8 million social media users could have seen the false report in their feeds, according to CrowdTangle’s analytics.

Cold hard facts don’t elicit much emotional response, ‘fake news’ does

Disinformation is a political exercise, says Aries Arugay, a political science professor at the University of the Philippines. The fact that most of his happens online, especially in Facebook, does not mean that its effects are limited only to consumers of social media.

“Facebook has a ripple effect,” Arugay explained, saying there is a certain “mysticism” around disinformation even for those who are not active on social media, but who have heard of such from others. “It’s like my father. Every time I hear him say ‘Oh, I heard that this was on Facebook. So it must be true.’ In a way, there’s some mysticism and that contributes to fake news,” he said.

The Duterte camp confirms that its use of social media strategies for the presidential campaign in 2016 set him apart from his opponents. These offered his election team a relatively less expensive mode of courting votes in a country where poll campaigns rely heavily on the ability to hold rallies crisscrossing this archipelago of 7,100 islands and to place expensive political ads in different media.

“We used social media because we did not have the money,” Nic Gabunada, who headed the social media campaign of Duterte, had told Vera Files in an earlier interview.

“I know there are shortcomings,” Gabunada said in response to accusations of online abuse and bullying that occurred during the 2016 election period. “Since this is a movement, you cannot control everybody.”

That proactive social media strategy paid off. Pledging to kill drug dealers and criminals, Duterte won the presidential vote with more than 16.6 million votes, edging out his closest rival by more than 6 million votes. But in the years since that victory, the social media campaigns around the President have not waned – and have in fact metamorphosed into a continual wave that defends and promotes him across social media spaces.

Arugay says the continuing presence and activity of social media networks supportive of the administration even after the elections could mean that their usefulness lies not only in getting votes. “The would-be government was not simply trying to win votes – they were trying to create a support constituency,” Aru gay said.

And, Arugay added, it appears once people have been roped into this constituency, online disinformation only fuels more of the same support such that “it’s path-dependent, there is no turning back.”

“Cold hard facts don’t really elicit much emotional response,” he said. “It’s really ‘fake news’ that translates to freezing of political lines, that translates (into) selection bias, because fake news always somehow elicits an emotional response – anger, passion, support, fanaticism.”

Explained Arugay: “Political mobilization is often driven by non-rational considerations more than rational ones.”

(This story was produced under the Southeast Asian Press Alliance 2018 Journalism Fellowship Program, supported by a grant from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights [OHCHR]. The views expressed herein can in no way be taken to reflect the official opinion of OHCHR.)