Spirited Traces, the third and last series of the Santiago Bose exhibition project by Silverlens Galleries, runs until May 20, 2023. The first one, Bare Necessities, opened in 2019, followed by Striking Affinities in 2021, with Patrick Flores as curator of the three series.

Composed of Installation, Cross-Reference, Inscription, Collage, and Palimpsest, the exhibit includes the artist’s Studio Memorabilia and Unfinished Projects. Overall, Bose’s work expressed a strong sense of Filipino roots, particularly its indigeneity and folk sensibilities. Reclaiming the power of indigenous cultures, Bose’s art has attempted to reframe our sociocultural perspectives amidst the barrage of Western influences.

Bose’s influence on contemporary Filipino artists remains to be recognized, with “his ideas, forms, and ideology in various media” being co-opted by artists, as the Yuchengco Museum has noted in a 2010 retrospective exhibit.

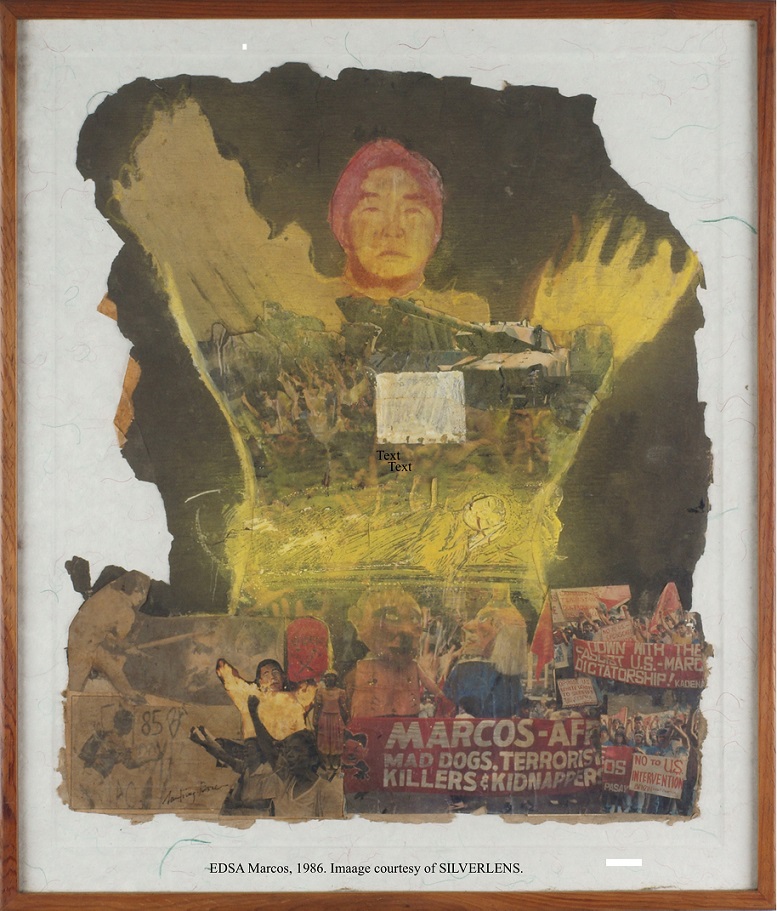

Social reality

Barikada (1998): A different kind of barricade, a folk takeoff from the rallying cries of the 1970s, “Let’s barricade!” The cries have not been silenced in exposing the same issues: insidious poverty, loss of democratic process, and lack of social justice in the country, to this day.

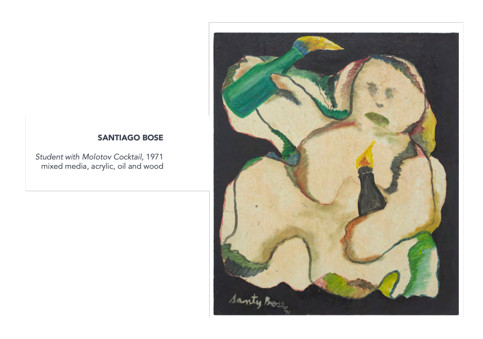

In Student with Molotov Cocktail (1971): one remembers the tumultuous years under the Marcos regime, where protests and demonstrations occurred frequently, spearheaded by students, workers, and farmers. Protest banners and songs flooded the streets and inevitably, the police and the military reared their ugly heads, again and again.

Early OFWs

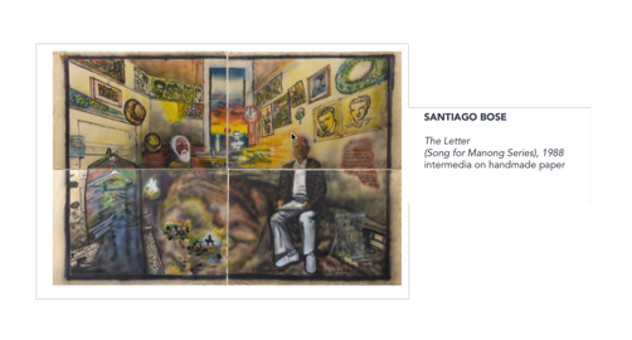

The Letter (Song for Manong Series, 1988): The work addresses the lives and times of the Manongs, the first generation of Filipino migrants in the 1920s and 1930s to the United States. A term of respect and affection, Manong also means “older brother.” Mostly from the Ilocos region, these single men worked as farm laborers in California and Hawaii in search of the American Dream. Faced with racism, discrimination, and exploitation, they played a significant role in the labor and farm worker movements in America, organizing strikes and work stoppages, as well as forming unions.

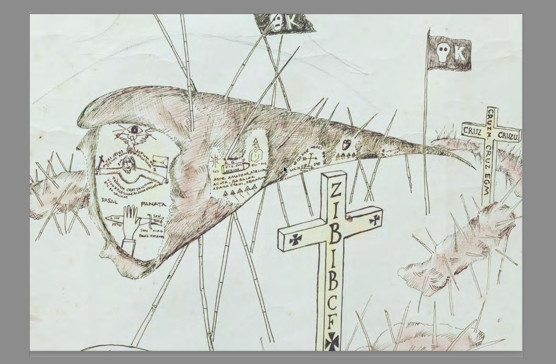

Folk religiosity

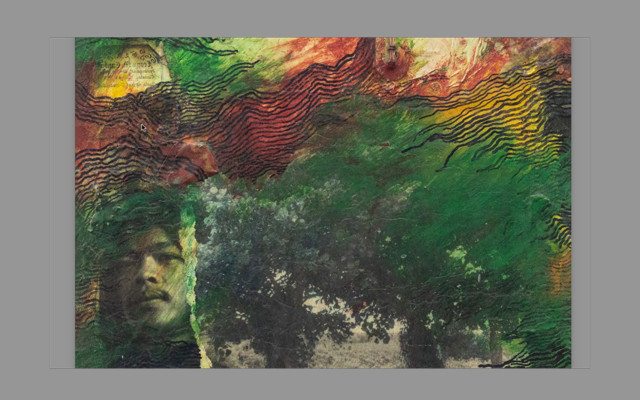

Mount Banahaw (2002): Considered as a holy mountain and believed to have curing powers, myths and folk stories of healing and miracles connected with the inactive volcano swirl around. Pilgrims visit the site, especially during Holy Week. Members of the Rizalista cult live at the foot of the mountain.

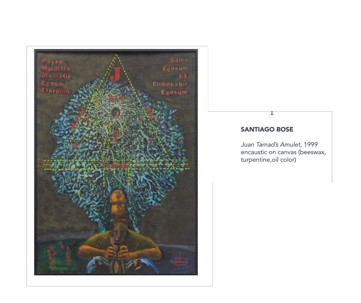

Juan Tamad’s Amulet (1999): Initials or groups of letters or gibberish words are often included in Bose’s works, a reference to anting-anting or folk amulets, symbolic of the power of the powerless.

Bose had admired the works of Reynaldo Ileto, the author of Pasyon and Revolution: Popular Movements in the Philippines, 1840-1910, 1979, who advocates “history from below,” that is, from the masses.

Santiago Bose (1942-2002)

A master of mixed media, Bose had been exploring “the possibilities of local materials in contemporary forms.” One of the earliest artists to use local craft materials, he used bamboo and volcanic ash and fibrous plants such as cogon, abaca, banana, or rice straw and local plant dyes in making handmade paper that he incorporated into his work. Found objects and old photographs were often embedded in his artworks as well.

Born in Baguio, Bose initially studied architecture at the Mapua Institute of Technology (1965-1967) and graduated with a fine arts degree in 1972 from the University of the Philippines Diliman. He continued his art studies at the West 17th Print workshop in New York City. Later, he was a visiting research fellow in 1994 at the Southern Cross University, Australia, and a visiting artist-in-residence in 2000 at the Pacific Bridge Gallery in Oakland, California.

Early in his eight-year stay in New York, Bose dared to quip that New York is not the center of art; “my heart is the center of art. The artist’s heart is the center.”

An active participant in major international exhibitions, he was featured in the Havana Biennial (1989), the Third Asian Art Show (1989), Fukuoka, Japan, and the First Asia Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, 1993 in Brisbane, Australia. Bose’s artworks were also featured in the 1996 exhibit Memories of Overdevelopment in University of California, Irvine and the 2020 exhibit At Home and Abroad: 20 Contemporary Filipino Artists at the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.

Beyond visual art, Bose was engaged with the community-at-large as reflected in his writings and organizational work. A co-founder of the Baguio Arts Guild, he served as its president in 1987 and 1992 and played in key role in establishing the Baguio International Arts Festival.

A recipient of the Thirteen Artists Award from the Cultural Center of the Philippines in 1976, he was awarded the Gawad ng Maynila: Patnubay ng Sining at Makabagong Pamamaraan in 2002 by the City of Manila. He was honored posthumously with the Gawad CCP Para sa Sining Award for Visual Arts in 2004. In 2006, he was shortlisted for the National Artist Award. In 2017, he received the Tanglaw ng Sining award from the UP College of Fine Arts.