A series of exhibitions on the art and life of Santiago Bose

(1949-2002), entitled Santiago Bose: Painter, Magician, has been set

in motion by Silverlens Galleries, Makati. The first phase, Bare

Necessities, is focused on Bose’s artistic language and how it is

used to produce a distinct form and critical discourse. It is on view

until 14 September 2019. The gallery plans to have an annual exhibit

on Santiago Bose in the next four years.

Bare Necessities presents an organic framework in which to understand

the inner dynamics that propelled Santi Bose to create works that are

indelibly stamped as his own, no more and no less. The exhibition is

divided into seven sections: Abstraction, Time/Ground, Archive,

Tricky Object, Potent Ornament, Everyday Life of Artist, and Acting

Out.

Curated by Patrick D. Flores, professor of art studies, University of

the Philippines and curator of the U.P. Vargas Museum, as well as the

artistic director of Singapore Biennale 2019, the exhibition presents

25 artworks, mostly paintings and prints from 1971 to 2002. An

additional ten objects of sketches, studies, and journals are

displayed on a long table.

Pushing Boundaries

As a mixed media artist, and with a body of work consisting of some

5,000 works of art, prints, drawings, paintings, sculptures, and

installations —Bose experimented with indigenous materials early

on, using what was available locally. He had used cogon, banana,

abaca, rice straw, bamboo, and volcanic ash from Mt. Pinatubo, as

well as all sorts of found objects, or what others would consider

trash.

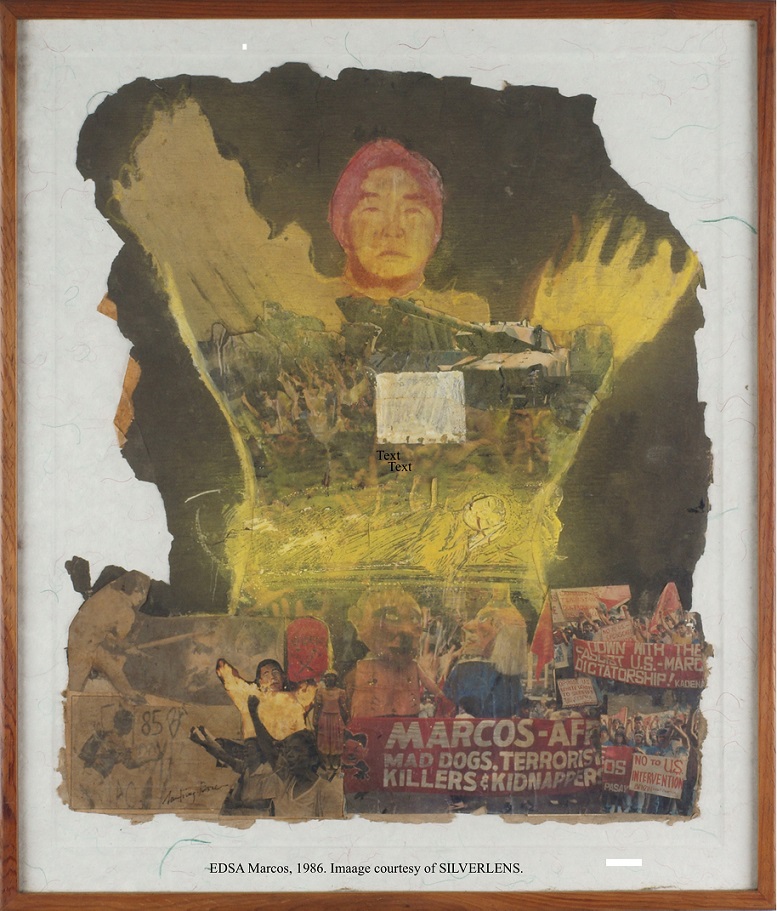

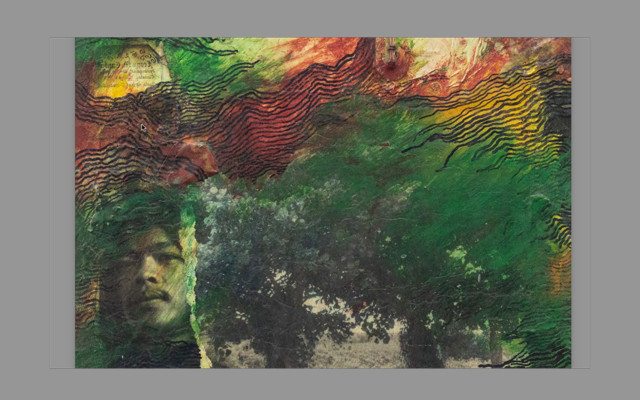

Highly textured and tactile, his paintings are embellished with

layers of collage upon collage, cutout images, old photographs, text,

poetry, or even small sculptural pieces added on to the painting

surface. He would also cut out small rectangles or squares in the

canvas itself and insert some other pictorial elements.

In Bose’s unfinished mural, 9-11 Return of the Comeback (2002), he

used Picasso’s Guernica as a metaphor for war, added with a Statue of

Liberty, as well as old photographs of Americans and Filipinos to

signify the return of American military occupation of the country, in

the aftermath of 9-11. In a short video interview a day before his

death, Bose talked about this mural and said that he wanted to add

some Abu Sayaf images, and more.

His creative ingenuity pushed him further to explore ideas and

materials, and embed them in his talks, in his performance art, and

in his engagement with communities.

“Santiago Bose 101”

In a talk at the gallery with Lilledeshan Bose, the artist’s

daughter, and Patrick D. Flores before the exhibition opening, Flores

sums up his own interest in curating Bose. As an art historian, he is

most interested in the evolution of Bose’s artistic language, from

abstraction to the artist’s relationship with image. And how that

image is transformed into a picture through all sorts of techniques,

e.g., collage, photo transfer, or intermedia. Flores also noted that

Bose’s early contemporary practice had been rooted in a particular

locality (Baguio and the larger Cordillera communities) that did not

smack of localism, regionalism, or by being simply exotic. In doing

so, Bose was able to transcend the local-global binary. Moreover,

Bose’s legacy also lies in the expansion of the post-colonial archive

in terms of imagery and technology through which images could be

combined to produce new forms. Flores added that while such practice

is not entirely new, there is a high level of idiosyncracy and humor

in Bose’s art production. In other words, Bose’s style is Bose.

The Artist

Born to working class parents in Baguio City on 25 July 1949,

Santiago Bose’s identity had been impinged by the long and dark

shadow cast by the former U.S. military base Camp John Hay,

1903-1991. As described by Lilledeshan, “he was always made

aware how ‘othered’ Filipinos were in their own country.” He

explored the effects of colonialism and imperialism on the Filipinos’

national identity. And he focused on the resilience and struggles of

indigenous cultures as exemplified by the peoples of the Cordilleras

in Northern Luzon.

He studied architecture at Mapua Institute of Technology, and shifted

to fine arts at the University of the Philippines, 1967-1972. He

continued his studies at the West 17th Print Workshop in New York,

1980-1981. After the downfall of the Marcos regime, he went home to

Baguio in 1986. He was one of the cofounders of the Baguio Arts Guild

and twice its president. His awards and recognition include the

Tanglaw ng Sining Award by the UP College of Fine Arts, 2017; Gawad

CCP Para sa Sining award, 2004, Gawad ng Maynila Award for visual art

in 2002, and the Thirteen Artists Award, Cultural Center of the

Philippines, 1976. Artist residencies include stints in Canada,

United States, and Australia.