Dominic and Mitzi Barrios, who have three children all under five years old, have been using a type of child restraint system (CRS) that most Filipinos have known and used for decades. It is warm, comforting and readily available.

A tight embrace, however, will never be enough to handle the forces of a road crash. Thus, the Barrioses are interested in a CRS that can better protect their kids and millions of other Filipino children.

“When we travel, we always take a nanny for our two toddlers, the baby, my wife and me, the driver,” Dominic Barrios told VERA Files.

“We haven’t adopted the CRS yet because we are still looking for more guidelines on what car seats for children are allowed, have quality standards and value for money,” he added.

The Department of Transportation (DOTr) released last month the draft implementing rules and regulations (IRR) of Republic Act 11229, also known as the Child Safety in Motor Vehicles Act, and held a public consultation on the guidelines.

The law, signed by President Rodrigo Duterte in February, is one of the government’s responses to what the World Health Organization (WHO) calls the top killer of people aged 5 to 29 years old worldwide – road crashes.

The 2018 WHO Global Status Report on Road Safety found that four in five road-traffic deaths around the world in 2016 occurred in middle-income countries like the Philippines.

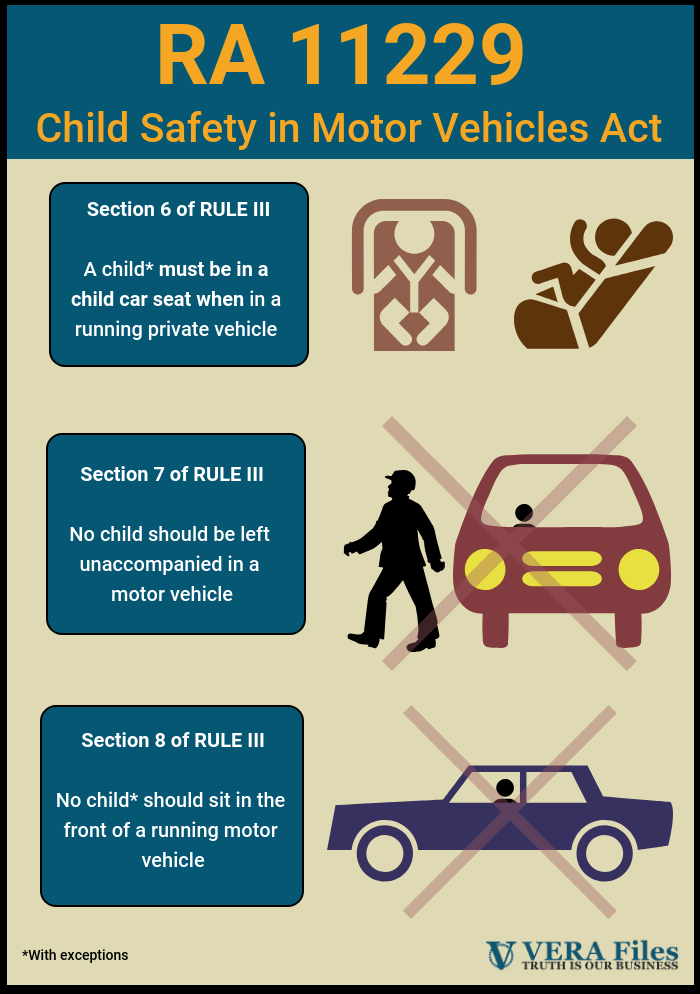

The car seat law requires private vehicle drivers to ensure that passengers who are 12 years old and younger that are 4’10” and shorter are secured with CRS when riding a car.

It also states that only passengers who are 13 years old and older can use the front passenger seat provided they are buckled up. The law likewise punishes drivers who leave children in a car unaccompanied.

The WHO said child restraints are “highly effective” in reducing injury and death to child occupants, with the greatest benefit for children under four years old. For children 8 to 12 years old, the WHO said using booster seats reduced the risk of injury by 19 percent compared to just using a seatbelt, which is normally designed for adults.

Draft IRR of RA 11229 by VERA Files on Scribd

To ensure product quality, the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) is mandated to adopt standards set forth under United Nations safety regulations for child restraints.

Under the draft rules, manufacturers, importers, distributors and sellers of CRS are required to secure from the DTI Bureau of Product Standards (BPS) a PS Mark License prior to the marketing, sale and distribution of their products.

The draft IRR requires the DTI-BPS to release technical regulations for child restraint certification within six months of the passage of the final IRR. The agency must also periodically publish a list of brands that meet these regulations.

Child restraints acquired prior to the full implementation of R.A. 11229, which is expected in September 2020, may be used so long as these are not substandard and have Land Transportation Office (LTO) clearance.

“We would not want those products to go to waste, so we wanted to set in place a mechanism for having these child-safety devices also approved and to make sure that they meet the safety standards in the law before we allow them to be used on the road,” lawyer Evita Ricafort said at the public hearing on Aug. 22.

The IRR states that the LTO clearance can only obtained up to one year after the full implementation of the law.

Importers of the child restraints suggest that the government issue a preliminary list to guide consumers who are unsure whether or not to purchase the device before the law is fully implemented.

“Our concern is that our customers might ask us, ‘What happens if we have no sticker, we might get apprehended’ ” said Europlay Sales and Marketing Manager Pierre Flores.

“From our end, we want to give consumers assurance that it’s OK to buy now,” he added in Pilipino.

Are ‘expired’ child restraints OK?

One issue that was raised at the consultation is the expiration of the safety device.

Section 9 of the IRR states that it is illegal to use or sell expired CRS. Meanwhile, Section 14 states that CRS without expiry dates may be used as long as they are not deemed substandard.

Experts are divided over the need for expiry dates, which are normally applied to U.S-made child restraints.

“Our Australian consultant said that it should not be an issue because there is really no expiration for child restraint systems,” said Dr. John Juliard Go of the WHO.

“But there are also other technical reports and other opinions from child restraint experts that it is an issue,” he added. “As a matter of fact, they give a timeline of a CRS that it expires roughly eight to 10 years after the date of manufacture.”

Go said the IRR’s provisions on expiry dates could be revised as more scientific evidence emerges. Meanwhile, visible signs of wear and tear could indicate the trustworthiness of the device.

No cracks, no tears, no frays

Section 13 of the draft IRR also outlined what “substandard” child restraints are. Besides not having an Import Commodity Clearance Mark or Philippine Standards Certification, substandard CRS include those that:

- Are covered by a product or safety recall

- Show the following upon visual inspection:

- Cracked or damaged plastic shell and/or metal component/s

- Frayed harness or tether strap, or broken stitching along the harness or tether strap

- Twisted, torn or abraded webbing strap

- Quick release buckle that does not engage or disengage smoothly

- One or more missing parts

- Other substantial damage visible to the eye

Subsidies, rental schemed eyed

Section 25 of the draft IRR further states that “the DOTr shall, in consultation with the DTI, develop or support measures to promote the accessibility and affordability of child restraint systems.”

“Among the measures would include rental schemes or subsidies or providing loans to families,” said Ricafort of ImagineLaw, who was among the people who helped craft the implementing guidelines.

The cost of a CRS is one of the issues being raised ahead of implementation of the law.

Non-government organization Initiatives for Dialogue and Empowerment through Alternative Legal Services, Inc. said rear-facing child restraints, which are for infants under one year old, are available for as low as P1,299.75. The cheapest combination child restraint, which can be used for all ages, is P2,968.28.

Road advocates have argued that the prices are affordable and are miniscule compared to medical expenses that could be incurred if a child is harmed because he/she is not secured in a car seat.

The matter of a subsidy still has to undergo further study as the law doesn’t immediately provide for opportunities for cheaper CRS, although the private sector is willing to provide incentives for customers, said lawyer Rhia Muhi of the Global Health Advocacy Incubator.

“The market itself is also supporting that measure,” she pointed out “as you will come across offers that will allow you to exchange your old one for a discount on a new one,” she said during the consultation.

Nonetheless, Dominic Barrios believes that the IRR should be more specific on what assistance could be provided.

“The idea of providing financial assistance like discounts will be most helpful,” he said. “Maybe this option can be included in the statement of Section 25, as well,” he said in an interview.

‘Trauma-free’ apprehensions

The rules provide that the driver of any vehicle carrying a kid not buckled up will be held liable and in no instance will an enforcer be allowed to hold the child so as not to cause trauma.

Only a visual inspection will determine if the child is properly strapped to “ensure that child passengers are not subjected to any form of distress during the apprehension.”

Police Supt. Oliver Tanseco, chief of the PNP Highway Patrol Group Operations Management Division, said it could be traumatic for a child to see a policeman in uniform, who could be carrying a firearm, flagging down a vehicle and approaching it.

“When we started the Technical Working Group for the IRR, it was very clear, we should not traumatize the child,” he said.

“The child will not be asked to step out of the vehicle, be measured, asked for an I.D., nothing like that.”

Atty. Robert Valera, LTO Law Enforcement Bureau chief, said the agency is still developing protocols to train enforcers on how to deal with children based on a minimum engagement policy.

LTO chief Edgar Galvante, meanwhile, warned enforcers not to measure the success of road safety laws by the number of apprehensions.

“In one meeting I attended, we called the attention of one enforcer who said his office’s performance was good after reporting the number of apprehensions and the amount of fines collected,” he said at the consultation.

“It is not an indication of a program’s success if we see more violators or more penalties collected, as well as more road crashes,” Galvante stated.

Ricafort, meanwhile, said support for the use of child car seats should continue, instead of being derailed by debates over expiration or pricing. “Let’s move forward despite the constraints.”

The DOTr said it plans to conduct more consultations outside of the capital, adding that the public may also send suggestions online to the agency to help refine the draft IRR.

The final IRR is expected to be released this month and the law will then be fully implemented one year after.

This story was produced with the help of a grant from The Global Road Safety Partnership (GRSP), a hosted project of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC).