Should the Marcos Jr. government be believed, 2025 was a year, once again, of “bloodless” drug war—even with 269 reported drug-related killings.

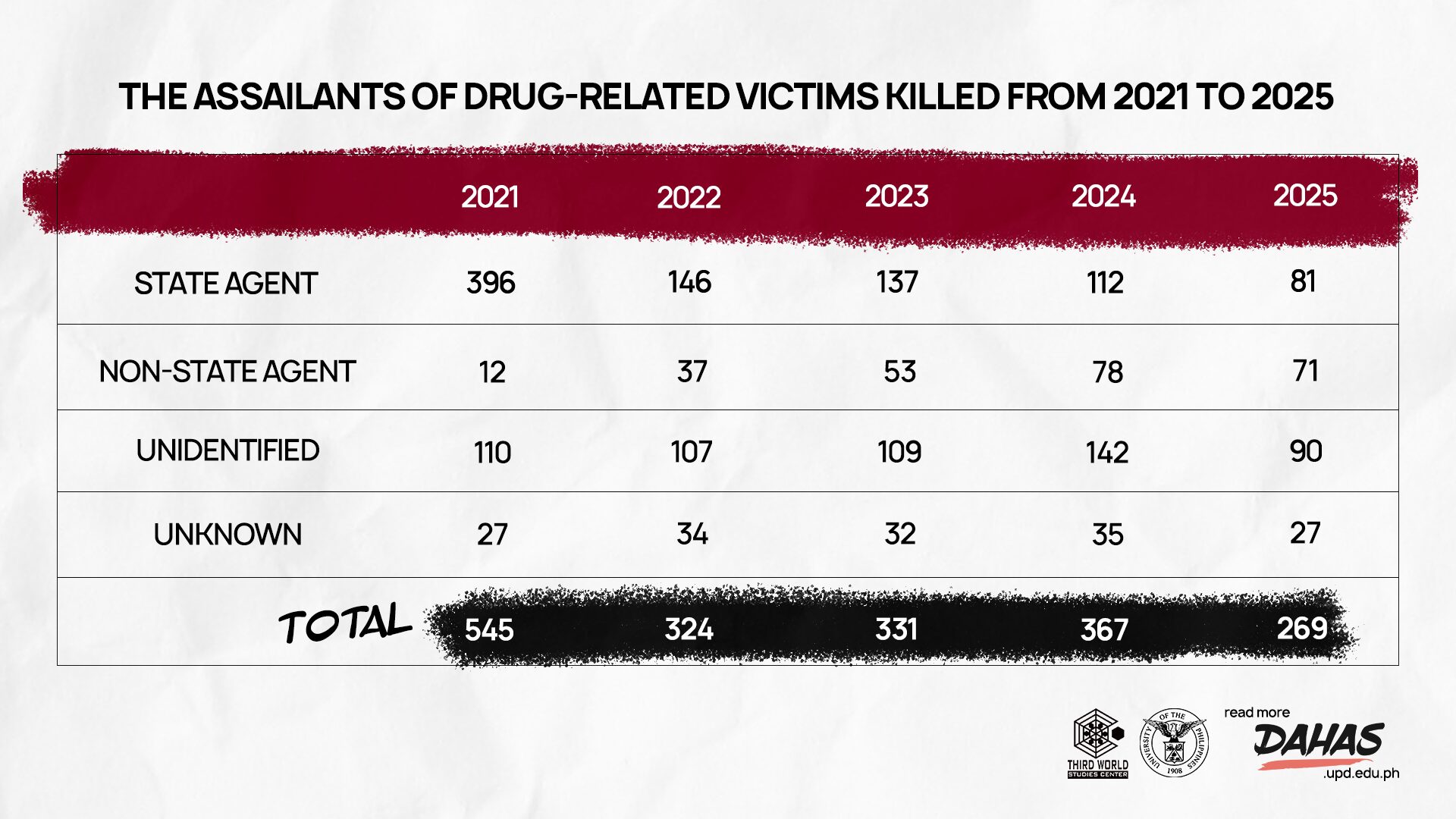

The Dahas Project of the UP Third World Studies Center counted 269 reported drug-related killings, 81 of which were committed by the police and other state agents during anti-illegal drugs operations. In turn, four police officers, three Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) agents, and 10 police informants were killed by the criminals involved in the drug trade. Only in government propaganda and its years of magical thinking can “bloodless” mean this much death.

And there is no indication that it will reckon with its own drug-related killings or those committed by other criminals running the illegal drug trade. For the PNP, there is no such thing. In a recent statement reacting to the Human Rights Watch 2025 report on the Philippines, Philippine National Police (PNP) Chief Gen. Jose Melencio Nartatez Jr. “disputed claims that drug-related killings involving police officers or unidentified assailants have continued under the Marcos administration.”

Nartatez’s blanket denial erases even an earlier admission to the contrary by a previous PNP chief. In November 2022, five months into the new Marcos administration, then PNP Chief Gen. Rodolfo Azurin Jr. admitted that at least 46 individuals were killed by the police in anti-illegal drugs operations. And as proven by the Dahas Project, General Azurin was even undercounting the killings under his watch. For the same five-month period, the Dahas Project counted 71 drug-related killings committed by state agents.

Apparently, Nartatez is also neither aware nor does he credit the figures from PDEA, claiming that in “the past three years under President Marcos, 271 drug personalities were killed in operations.”

When the Marcos administration shifted from its supposed holistic and less bloody approach to the illegal drugs problem to a “bloodless” drug war, information on drug-related killings from the government dried up. If not for the news media, Nartatez’s baseless assertion could have easily been taken for the truth. But the news media, in particular the small local and provincial presses, continue to cover such killings. From them, the Dahas Project draws its data.

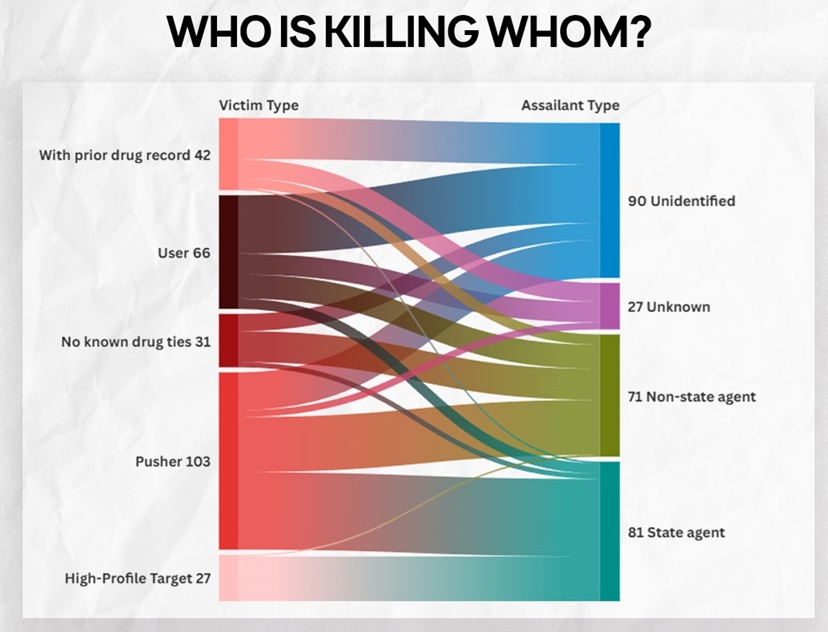

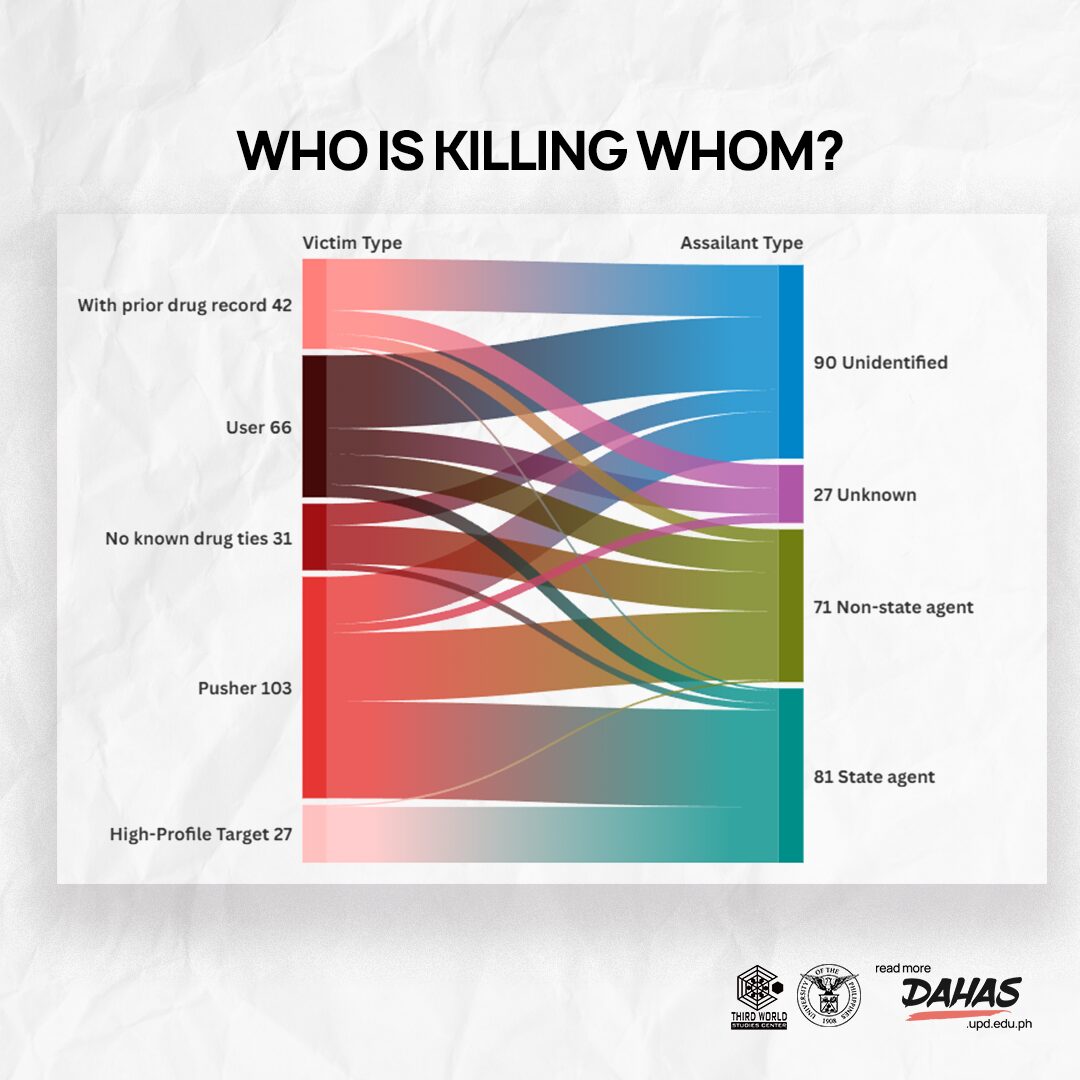

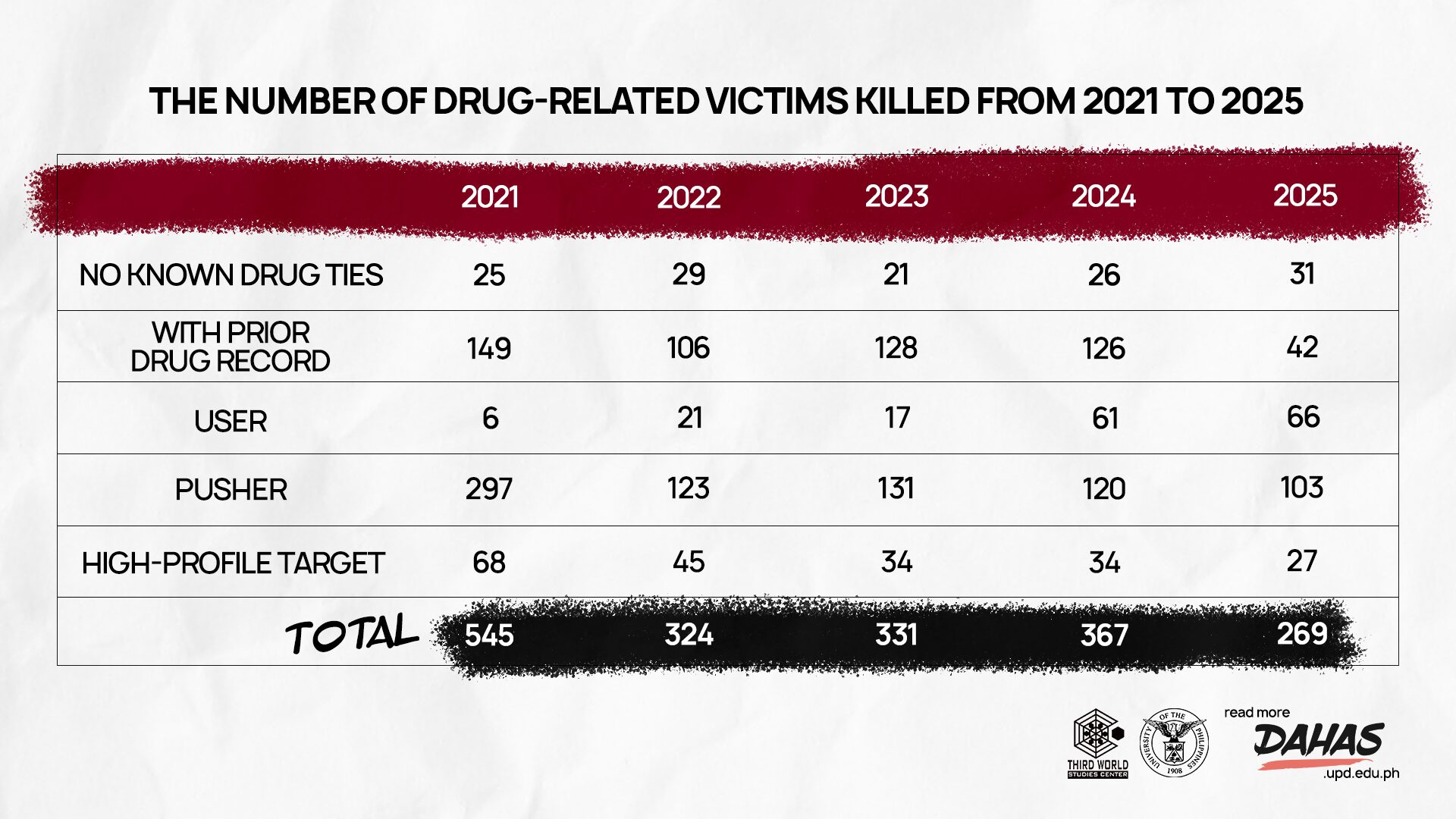

In 2025, the Dahas Project logged 269 reported drug-related killings, a 26.7 percent decrease from the 367 cases that it recorded in 2024—less deaths, yes, but again, not bloodless at all. This is the lowest recorded number of drug-related killings since 2021 when the Dahas Project started its weekly monitoring. Most of those killed in 2025 were identified in the news reports as pushers. State agents and unidentified assailants were the main perpetrators of the killings.

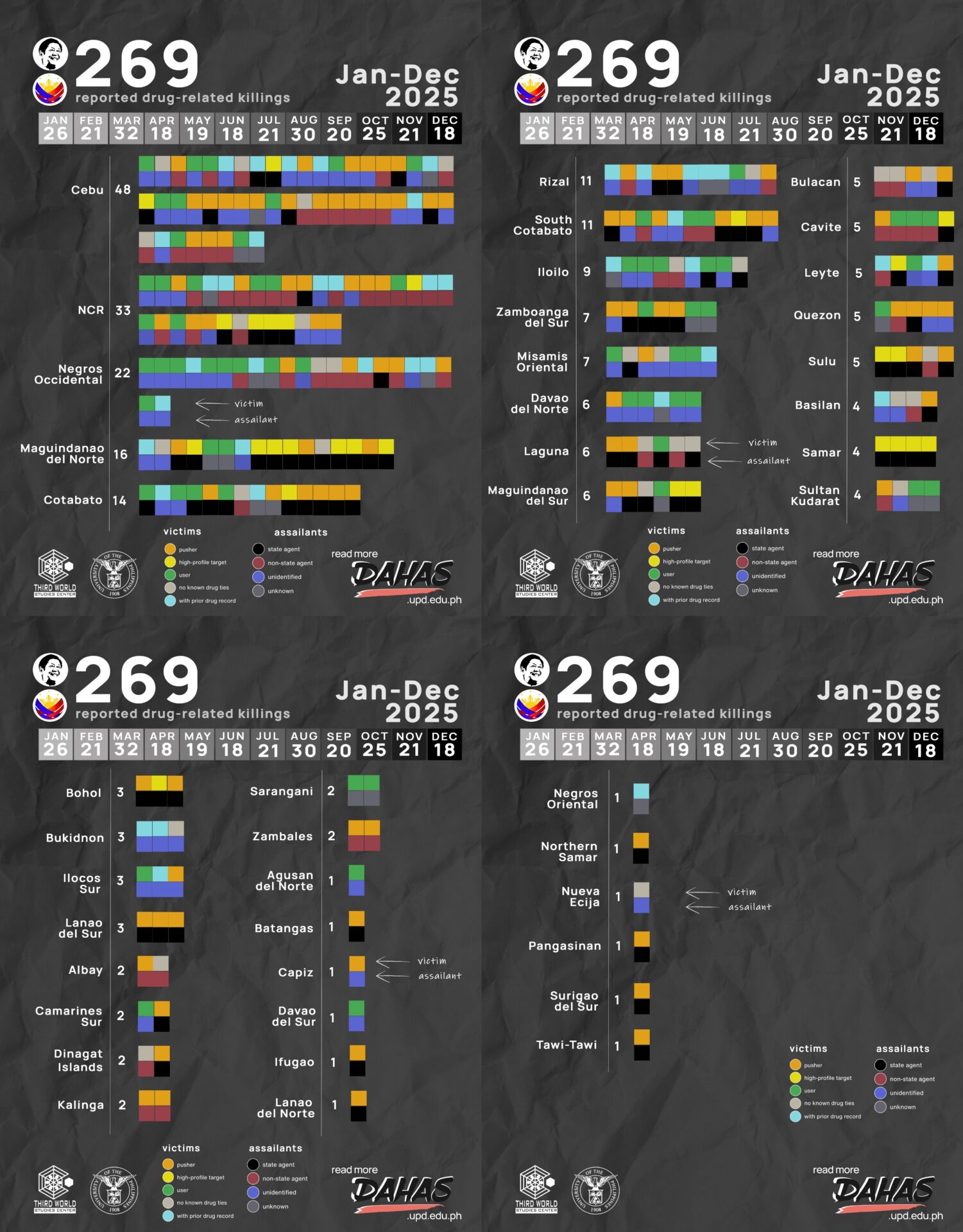

Of the 269 killed, 103 or 38.3 percent were pushers. Users follow at 66 or 24.5 percent. Meanwhile, victims with previous drug records (for example, those who were included in drug watchlists or have served time in drug-related charges) came third at 42 or 15.6 percent—a 22.9 percent decrease from 2024, and the lowest count since 2021.

In contrast, this year marked the highest number of victims with no known drug ties recorded by the Dahas Project at 31 or 11.5 percent. Included in this number are the seven state agents mentioned earlier and the 10 police informants. The rest of those killed were either caught in the crossfire during an operation, mistaken for a different target by an assassin, or marked out as target for revenge by someone who thought they had double-crossed in a drug deal. Three were minors.

This year, seven state agents, who were officers of PDEA and PNP’s Drug Enforcement Unit (DEU) and Special Action Force (SAF), were killed. Six were caught in escalated shootouts that transpired with suspects who resisted arrest. Meanwhile, P/Corporal. Joseph Toribio, who was active in anti-illegal drug operations, was shot and left for dead along a highway in Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija. His killer remains unidentified.

In Maguindanao del Norte, a buy-bust operation intended to dismantle a drug den in Barira led to the killing of drug suspect Samsurin Baraguir alias “Robot,” and his 15-year-old daughter, who was caught in the shootout that ensued against joint police forces. In another case, Nadine Tanghal was found dead in her home in Cotabato City, hours after her partner was arrested for his involvement in illegal drug activities. Tanghal had no recorded drug involvement, but according to reports, the killing could have been linked to drug suspects attempting to silence her.

Jason Garcia was among the 10 killed for being suspected as a police asset or informant in drug cases. On September 12, he was shot outside his home in Cebu City by two unidentified gunmen. Garcia was identified as a police asset, but another angle was also considered—the killing was a case of mistaken identity. Garcia’s twin brother had been detained for drug-related charges. In another case, Aurelio Bañagaso alias “Auring,” a person with disability, was killed after being suspected to be a police asset by Noel Rosero, a drug personality and HVI. Rosero was killed by the police in a hot pursuit operation. Meanwhile, in Cagayan de Oro, a Master Sergeant of Divisoria Police Station killed police asset Henry Mendoza Pimentel alias “Opaw.” According to the police, the killing may have had something to do with illegal drugs.

All the while, the PNP incentivizes the engagement of assets or informants. Millions worth of cash incentives were awarded to 30 police informants by the end of 2025.

At 27 or 10.0 percent of the total, high-value targets are the least in the Dahas Project’s 2025 count. Except for one, all were killed by state agents during operations. The exception was a case in Taguig City where a high-value target who had just shot another person allegedly involved in the drug trade was, in turn, shot by an armed civilian who chanced upon him as he was fleeing. Most high-value targets were killed in Maguindanao del Norte (7), the National Capital Region (NCR; Metro Manila) (5), and Samar (4). Cebu, Sulu, and Maguindanao del Sur had two each. The rest were in South Cotabato, Bohol, Cavite, Cotabato, and Leyte. Since the Dahas Project started its monitoring of drug-related killings in 2021, those killed as high-value targets have never breached the 10 percent mark.

In mid-2025, the Marcos administration, just like the others before it, maintained that it would target not only high-level drug personalities but also small-time drug traffickers. If one would go by the percentages of the killings discussed in this report, the Marcos administration may have succeeded in its efforts with the former and failed in the latter. But the government is not the only player in this deadly game.

The Dahas Project refers to unidentified assailants as those seen by witnesses or captured in video recordings but with insufficient information to identify them by name and in person. Those who were positively identified as private individuals or members of insurgent groups are categorized as non-state agents. And the assailants that were not seen by any witnesses and usually those responsible for cases of body dumps are classified as unknown assailants.

For the second consecutive year, unidentified assailants predominated with 90 killed or 33.5 percent of all the killings. State agents came second with 81 killed. While there is a decrease in the number of victims killed by the state, the proportion of victims killed by state agents to the total killed in 2025 remained close to that of 2024: from 30.8 percent to 30.1 percent. State agents have mainly killed pushers (45 of 81).

Non-state agents follow with 71 killed or 26.4 percent of the total killed; notably, they account for the majority of victims killed with no known drug ties (18 of 31). Meanwhile, 27 or 10.0 percent remained with unknown assailants.

Males comprise most of the victims at 245 or 91.1 percent of the total killings; only 19 or 7.1 percent were females. Of all those killed, the sex of 5 or 1.9 percent was not reported.

A larger number of victims had no reported age group (87 or 32 percent). But similar to 2024, the majority of the victims are in the 30–39 age group (65 or 24.2 percent), followed by victims between 40–49 (49 or 18.2 percent) and 20–29 (45 or 16.7 percent). The rest of the victims were between 50–59 at 14 or 5.2 percent, 13–19 at 8 or 3.0 percent, and 60–69 at 2 or 0.7 percent.

There were no recorded victims below 13 years old. However, of the victims aged 13-19, four were reportedly minors/younger than 18. Among the youngest is a 15-year-old child who was held at gunpoint and used as a shield by a drug personality in Negros Occidental on June 11.

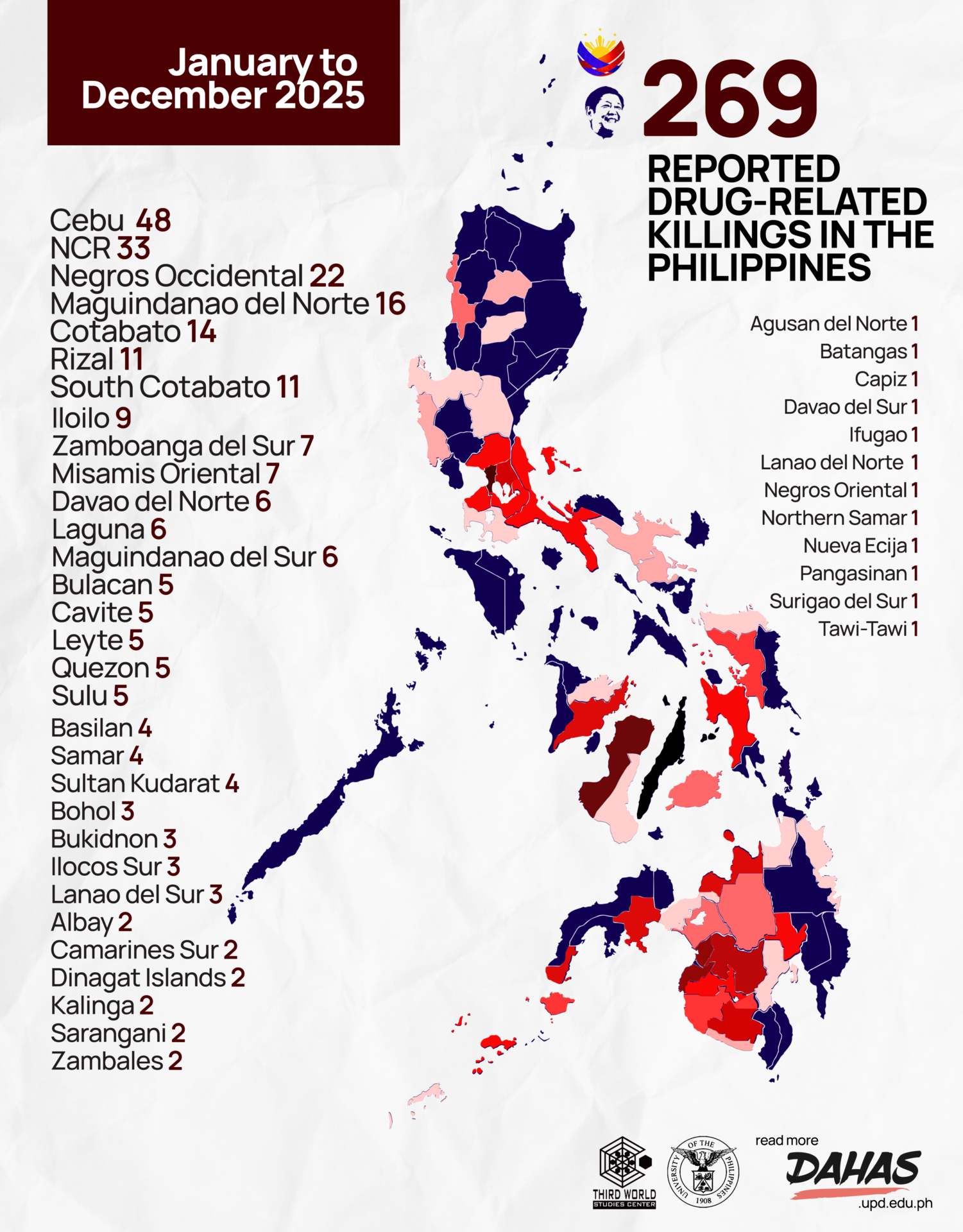

The drug war claimed most lives in seven provinces: South Cotabato, 11; Rizal, 11; Cotabato, 14; Maguindanao del Norte, 22; Negros Occidental, 22; NCR, 33; and Cebu, 48. This shows a continuing trend where most of the killings have shifted outside of NCR and into the provinces of Visayas and Mindanao. Davao City was the epicenter of the killings at the start of the Marcos administration until it was overtaken by Cebu.

Since 2023, Cebu has been the hotspot of the killings, accounting for no less than 15 percent of all the total killed in a year (52 or 15.7 percent in 2023, 76 or 20.9 percent in 2024, 48 or 17.8 percent in 2025). These years likewise saw in Cebu an increase in “vigilante” killings, or killings committed by assailants known to be non-members of the state forces. Or, as local news reports would identify them, hired killers.

The proportion of the killings committed by other criminal elements to the killings by state agents has been increasing since 2022. This year, it is at 188 or 69.9 percent. Vigilante killings in Cebu for 2025 alone comprise 42 of the 48 killed (21 unidentified, 16 non-state agents, and 5 unknown).

Meanwhile, in Mindanao, the killings perpetrated by state agents predominated in the neighboring provinces of Maguindanao (Maguindanao del Norte, 11; Maguindanao del Sur, 4), and Cotabato (Cotabato, 9; and South Cotabato, 3). These killings occurred during active police anti-illegal drug operations, primarily targeting low-level drug pushers and high-profile drug personalities.

Five victims were killed in a single incident in Cotabato—the highest number killed under such circumstances in 2025. The incident was a shootout between the police and military, and the members of a notorious drug syndicate in Kabacan.

It was also during these operations that the police continued to justify their killings using the now discredited “nanlaban” narrative—deadly retaliation becomes necessary against suspects who are said to be armed and resist arrest. In Maguindanao del Norte, Porok Marandakan Ragundo alias “Rokkie,” an HVI with multiple cases of murder and robbery, and his alleged accomplice, Jomar Inidal Dandungan, were killed in an encounter in a joint buy-bust operation of the police and the military on July 17. Dandungan was initially identified as a drug coddler who was killed after resisting arrest. However, later evidence held that Dandungan had no prior records of any drug-related or criminal activities in the barangay. The killing was suggested to be a case of mistaken identity.

As the Marcos administration continues to flaunt their relative achievements in a “bloodless” drug war—multiple arrests, tons of confiscated illegal drugs—repeatedly left out of these narratives are the still unmitigated violence that is increasingly perpetrated by criminal elements said to be outside the reach of state forces. And again, state agents continue to kill. The “bloodless” drug war continues, and more so, and as before, spills over to innocent civilians. Their increasing death count cannot simply be dismissed as insignificant casualties.

This 2026, PNP Chief Gen. Jose Melencio Nartatez asserted a “more aggressive yet responsible campaign—one that protects lives, upholds the rule of law, and strengthens public trust.” Would these lives finally include those who had been conveniently left out of their successful operations? But before that, when will General Nartatez acknowledge the fact that drug-related killings have been going on long before he became top cop and is expected to continue “bloodless” drug war propaganda, or not?

(Arrianne Louisse Fajardo and Joel Fajardo Ariate Jr. are researchers at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. They are in charge of the Dahas Project. Jules Politico helped prepare some of the graphics. To learn more about the Dahas Project, visit its website and for the latest updates, follow the Dahas Project in these social media platforms: X (formerly Twitter), Instagram, Threads, and Bluesky.)