By ROMEL R. BAGARES

JUST as pundits have predicted, China soon announced it is not taking part in the arbitration proceedings initiated by the Philippines over the two countries’ territorial dispute in the West Philippine Sea (South China Sea for the Chinese).

So, what happens next – does this mean an abrupt end to the Philippines’ quest for an effective legal solution to the riddle of the Chinese Nine-Dash Line claim?

Well, not quite.

Or at least, not yet.

The Philippine case against China was anchored on Annex VII of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

It’s therefore necessary to discuss first what an ANNEX VII arbitration is about.

The UNCLOS has specialized rules for dispute resolution among member states. Where the issue is the interpretation or application of the treaty –as the Philippines claims in this case – Part XV of the treaty applies.

Under Part XV, there are two ways of determining the venue for resolving disputes. Under the first mode, as soon as a state opts to become a party to the UNCLOS, in accordance with Art. 287 (1) of the treaty, it may identify one or more of the following bodies as means for settling disputes of interpretation or application of the law: (a) the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) in Hamburg, Germany; (b) the International Court of Justice in The Hague, The Netherlands; (c) ad hoc arbitration (in accordance with Annex VII of UNCLOS); or (d) a “special arbitral tribunal” constituted for certain categories of disputes (also established under Annex VIII of UNCLOS).

The second mode is a resort by default to ad hoc arbitration under ANNEX VII in the following situations: (a) if a State has not expressed any preference with respect to the means of dispute resolution available under Article 287(1) of UNCLOS and has not expressed any reservation or optional exceptions pursuant to Article 298 of UNCLOS; and (b) if the parties have not accepted the same procedure for the settlement of the dispute, subject to same exceptions or reservations under Article 298.

Simply put, unless the parties agreed to the contrary, the default mode for question of interpretation and application of the UNCLOS or relevant treaties is an arbitration under ANNEX VII.

The Opt-out clause in the UNCLOS

Membership in the UNCLOS means a state’s acceptance of compulsory and binding dispute mechanism procedures provided in the treaty.

However the treaty allows member states to opt out of these compulsory procedures under the so-called Art. 298 exceptions, which, among other things, pertain to disputes concerning military activities, including military activities by government vessels and aircraft engaged in non-commercial service, and disputes concerning law enforcement activities in regard to the exercise of sovereign rights or jurisdiction as well as sea boundary delimitations, or those involving historic bays or titles.

China has made such an exception in a formal declaration on August 25, 2006.

It is for this reason that in its Notification and Statement of Claims against China, the Philippines was emphatic that it is not submitting to arbitration any of the disputes covered by the reservations made by the former under Art. 298 of the UNCLOS.

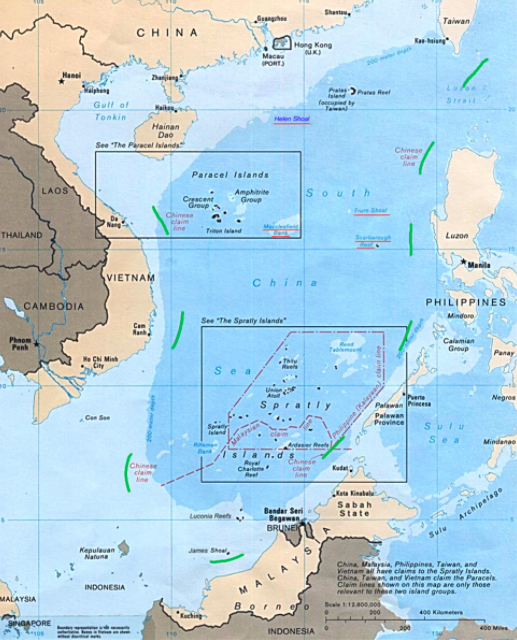

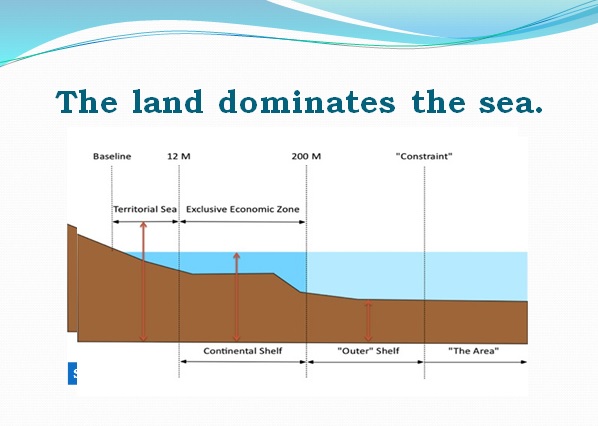

As my senior colleague, Prof. Harry Roque notes, “Our submission of claims is crafted in a manner that will exclude all of China’s reservations. For instance, the submission asked the tribunal to rule on the validity of the controversial ‘nine-dash line,’ since it does not constitute either China’s internal waters, territorial sea, or exclusive economic zone. This asks the tribunal to rule, as an issue of interpretation of the Unclos, whether the nine-dash lines comply with the Convention. Likewise, China has built permanent structures on reefs such as Mischief and Subi, which are permanently under water. The submission prays that the tribunal declare that since these are neither “rocks” nor “islands,” these should be declared as forming part of our country’s continental shelf, or the natural prolongation of our land mass.

“On Panatag, our submission asks the tribunal to declare that the six very small rocks permanently above water can generate only 12 nautical miles of territorial sea. This declaration, if made, will clarify that the waters surrounding the small rocks still form part of our 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone.”

Art. 3(b) of ANNEX VII says the party that initiated the proceeding appoints an arbitrator from a list provided by the UN Secretary General. The Philippines has already done so, following which China, within 30 days of receipt of the Philippines’ claim, may appoint its own arbitrator from the same list, [Art. 3(c)].

The other three members of the arbitral tribunal will be appointed by agreement of the parties, preferably from the UN list, and who are nationals of other states not party to the dispute, unless the Philippines and China agree otherwise.

Last Thursday however, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Hong Lei disclosed that China has rejected the Philippines’ resort to international arbitration, charging that the move contradicts the ASEAN consensus for bilateral negotiations.

Last Thursday however, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Hong Lei disclosed that China has rejected the Philippines’ resort to international arbitration, charging that the move contradicts the ASEAN consensus for bilateral negotiations.

Mr. Hong Lei was referring to the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC) which China signed along with members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 2000 (when the same document actually allows resort to UNCLOS mechanisms, as is stated for instance in DOC principles 1, 3 and 4.).

Given the Chinese evasion, now what?

Now, since China has already declined to take part in the proceedings, the Philippines, within two weeks of the expiration of that 30-day period, may request the President of the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) to appoint the needed appointments to form the ad hoc arbitral tribunal, including who will preside over it from the same UN list [Art. 3(e)].

A broad or liberal reading of Art. 3 would have the President of the ITLOS as getting to rule first on whether the ad hoc tribunal has jurisdiction to hear the case filed by the Philippines to begin with.

But under a textualist or literal reading of Art. 3, China is given the option to appoint an arbitrator to the tribunal and if it refuses to do so, the President of ITLOS – the incumbent is Japanese ex-diplomat and jurist Shunji Yanai –steps in to appoint an arbitrator on behalf of China from a list of arbitrators to be provided by the UN Secretary General, as well as all the other necessary appointments to put up the arbitral body. (Note that the arbitral tribunal referred to here is different from the ITLOS).

From there, even without Chinese participation, the tribunal may then decide that it has jurisdiction over the dispute – what legal scholars call the doctrine of kompetenz-kompetenz – hear the case on the merits, and thereafter render a judgment on default.

This is clear if the text of Art. 9 is considered:

“If one of the parties to the dispute does not appear before the arbitral tribunal or fails to defend its case, the other party may request the tribunal to continue the proceedings and to make its award. Absence of a party or failure of a party to defend its case shall not constitute a bar to the proceedings. Before making its award, the arbitral tribunal must satisfy itself not only that it has jurisdiction over the dispute but also that the claim is well founded in fact and law.”

Of course, this assumes that the tribunal has thought none of Chinese objections to its jurisdiction.

Yet, available precedents – there are only seven such arbitrations conducted under ANNEX VII since the UNCLOS took effect in 1994 – seem to tell the Philippines it has little cause to worry as far as jurisdictional grounds are concerned.

As one well-known international law academic observer has noted, ”the few Annex VII arbitral tribunals that have been constituted have generally not hesitated to rule on their own jurisdiction… Even worse from China’s perspective, these Annex VII arbitral tribunals issued their jurisdictional decision at the same time as they issued the award on the merits”(emphasis in the original)

Now, will a successful arbitration finally put an end to all of the Philippines’ problems in the West Philippine Sea?

Not quite. Or at least, not yet.

As Prof. Roque, explains: “The Unclos, after all, being the applicable law on the seas, cannot be utilized to resolve conflicting claims to islands. This aspect of the dispute will still be resolved on the basis of which claimant-state has the superior evidence of effective occupation. Nonetheless, a legal clarification on China’s claims to alleged islands and rocks that are under water, as well as the issue of which state can exercise sovereign rights on the waters surrounding Panatag, will simplify resolution of the entire dispute.

“If we are successful, what will remain for resolution is only the issue of conflicting claims to islands. While China will have to give its separate consent to litigate the status of these islands, at least the issue of freedom of navigation and the exercise of sovereign rights over a large part of the disputed waters will have a final and binding legal determination.”

Well, at the very least, an arbitration resolved in its favor could mean, more than anything, an immense political and moral victory for the Philippines, which has been portrayed by China – or by its mouthpieces – as the real troublemaker in the West Philippine Sea.

(Atty. Bagares has degrees in communication research and law from the University of the Philippines and earned a master’s degree on international legal theory from the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (cum laude). He lectures on public and private international law at the Lyceum Philippines University College of Law and serves as Executive Director of the Center for International Law, a non-profit dedicated to the promotion of the Rule of Law through international legal norms in the Philippines and Asia.)