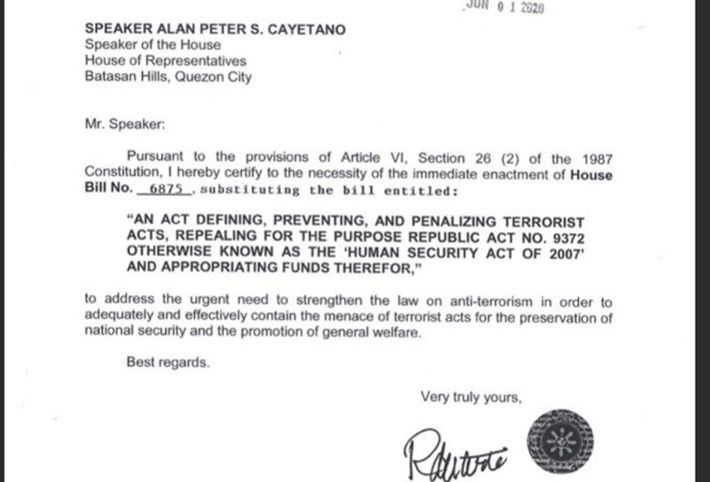

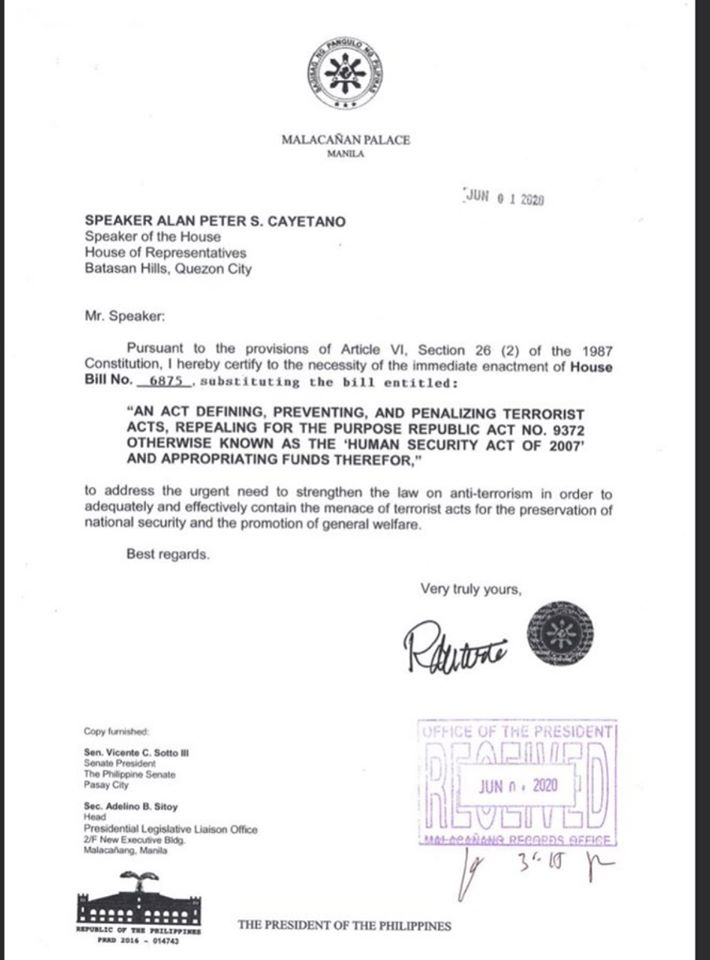

The controversial anti-terrorism bill, certified as urgent legislation by President Rodrigo Duterte, bears no “draconian provisions” but is needed because the Philippines has “one of the most lenient” anti-terror laws in the world, presidential spokesperson Harry Roque claimed in his June 2 press briefing.

The proposed legislation that will amend Republic Act 9372 or the Human Security Act (HSA) of 2007, Roque explained, is based on anti-terrorism laws in the United Kingdom, United States, European Union, and Australia. These countries have effectively dealt with terrorists and terrorism, he said.

Roque’s claims bear a closer look. Copying legislations inevitably leaves traces of imprecise borrowings and sometimes tortured improvisations to make the foreign suit the local and present needs. In comparing the degree of disfigurement wrought by the Philippine legislature on other laws they have copied from, we see the extent of power summoned to craft it. A proposed law that, critics argue, is not so much to combat terrorism but to give government unquestionable authority to brand anyone it pleases as terrorist, on mere suspicion, and to be severely punished as such.

In terms of domestic sources, the proposed law seems to draw provisions primarily from the existing HSA of 2007; RA 10168, or the Terrorism Financing Prevention and Suppression Act of 2012 (that implements United Nations Security Council Resolution 1373) from which it imported, then modified, provisions regarding the role of the Anti-Money Laundering Council (AMLC) in cutting off terrorists’ fund sources; and the Revised Penal Code, including those defining the crimes inciting to rebellion or insurrection and inciting to sedition. The wordings of “inciting to commit terrorism” closely follow those in these preexisting provisions, but are more general, as the table below shows. Of the three, its penalty for inciting to commit terrorism has the longest period of incarceration.

|

Inciting to Rebellion or Insurrection (Art. 138, Revised Penal Code) |

Inciting to Sedition (Art. 142, Revised Penal Code, as amended by RA No. 10951) |

Inciting to Commit Terrorism (Sec. 9, Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020) |

|---|---|---|

|

The penalty of prision mayor in its minimum period shall be imposed upon any person who, without taking arms or being in open hostility against the Government, shall incite others to the execution of any of the acts specified in article 134 of this Code, by means of speeches, proclamations, writings, emblems, banners or other representations tending to the same end. |

The penalty of prisión correccional in its maximum period and a fine not exceeding Four hundred thousand pesos (₱400,000) shall be imposed upon any person who, without taking any direct part in the crime of sedition, should incite others to the accomplishment of any of the acts which constitute sedition by means of speeches, proclamations, writings, emblems, cartoons, banners, or other representations tending to the same end, or upon any person or persons who shall utter seditious words or speeches, write, publish, or circulate scurrilous libels against the Government, or any of the duly constituted authorities thereof, or which tend to disturb or obstruct any lawful officer in executing the functions of his office, or which tend to instigate others to cabal and meet together for unlawful purposes or which suggest or incite rebellious conspiracies or riots, or which lead or tend to stir up the people against the lawful authorities or to disturb the peace of the community, the safety and order of the Government, or who shall knowingly conceal such evil practices. |

Any person who, without taking any direct part in the commission of terrorism, shall incite others to the execution of any of the acts specified in Section 4 hereof by means of speeches, proclamations, writings, emblems, banners or other representations tending to the same end, shall suffer the penalty of imprisonment of twelve (12) years. |

Recently, police officers have been filing dubious inciting to sedition cases against those promising in their social media posts bounties of astronomical amounts (that they clearly do not have) to anyone who would kill the president. It is not unreasonable to assume that in the proposed anti-terrorism act, the police may crudely apply the new law and go for “inciting to commit terrorism.” Arguably, it will have to be shown the killing of the sitting president will be done for the purpose of “[intimidating] the general public or a segment thereof, [creating] an atmosphere or [spreading] a message of fear, [provoking] or [influencing] by intimidation the government or any of its international organization [sic], or [creating] a public emergency or seriously [undermining] public safety” (section 4).

Under the proposed law, acts that a person will incite others to do specifically for the abovementioned purposes are limited to those intended to cause: “death or serious bodily injury to any person, or endangers a person’s life”; “extensive damage or destruction to a government or public facility, public place or private property; and “extensive interference with, damage or destruction to critical infrastructure.” Also included are “[developing, manufacturing, possessing, acquiring, or transporting, supplying or using] weapons, explosives or of biological, nuclear, radiological or chemical weapons;” and “[releasing] of dangerous substances, or causing fire, floods or explosions.”

Where do these definition of terrorism and list of terrorist acts — completely different from that in the 2007 HSA—come from?

The particular definition of “weapons of mass destruction” in the Anti-Terrorism Act (Section 3(n)) is identical to the one used by the United States Department of Defense for years—one of many provisions in the proposed law that clearly have foreign origins.

Those in Title 18, Chapter 118B of the United States Code (for instance, the definitions of training and providing material support to terrorists) and those in the (repealed) Council of the European Union framework decisions (especially 2002/475/JHA), eventually found their way in the proposed Anti-Terrorism Act.

As shown in the table below, the definition of terrorism in the proposed law seems to be a combination of those in 2002/475/JHA and Australia’s Criminal Code Amendment (Terrorism) Act 2003—both clearly hewing close to the definition of terrorism in the draft United Nations Comprehensive Convention on International Terrorism. The copying accounts for the odd, grammatically incorrect phrase, “and any of its international organization” in the proposed law.

|

Anti-Terrorism Act of 2020 |

European Council Framework Decision of 13 June 2002 on combating terrorism (2002/475/JHA) [repealed] |

Australian Criminal Code Amendment (Terrorism) Act 2003 |

|---|---|---|

|

[Sec. 4.] Subject to Section 49 of this Act, terrorism is committed by any person who within or outside the Philippines, regardless of the stage of execution: (a) Engages in acts intended to cause death or serious bodily injury to any person, or endangers a person’s life; (b) Engages in acts intended to cause extensive damage or destruction to a government or public facility, public place or private property; (c) Engages in acts intended to cause extensive interference with, damage or destruction to critical infrastructure; (d) Develops, manufactures, possesses, acquires, transports, supplies or uses weapons, explosives or of biological, nuclear, radiological or chemical weapons; and (e) Release of dangerous substances, or causing fire, floods or explosions when the purpose of such act, by its nature and context, is to intimidate the general public or a segment thereof, create an atmosphere or spread a message of fear, to provoke or influence by intimidation the government or any of its international organization, or seriously destabilize or destroy the fundamental political, economic, or social structures of the country, or create a public emergency or seriously undermine public safety, shall be guilty of committing terrorism and shall suffer the penalty of life imprisonment without the benefit of parole and the benefits of Republic Act No. 10592, otherwise known as “An Act Amending Articles 29, 94, 97, 98 and 99 of Act No. 3815, as amended, otherwise known as the Revised Penal Code”: Provided, That, terrorism as defined in this Section shall not include advocacy, protest, dissent, stoppage of work, industrial or mass action, and other similar exercises of civil and political rights, which are not intended to cause death or serious physical harm to a person, to endanger a person’s life, or to create a serious risk to public safety. [Sec. 5.] Any person who shall threaten to commit any of the acts mentioned in Section 4 hereof shall suffer the penalty of imprisonment of twelve (12) years. |

[Article 1] 1. Each Member State shall take the necessary measures to ensure that the intentional acts referred to below in points (a) to (i), as defined as offences under national law, which, given their nature or context, may seriously damage a country or an international organisation where committed with the aim of: — seriously intimidating a population, or — unduly compelling a Government or international organisation to perform or abstain from performing any act, or — seriously destabilising or destroying the fundamental political, constitutional, economic or social structures of a country or an international organisation, shall be deemed to be terrorist offences: (a) attacks upon a person’s life which may cause death; (b) attacks upon the physical integrity of a person; (c) kidnapping or hostage taking; (d) causing extensive destruction to a Government or public facility, a transport system, an infrastructure facility, including an information system, a fixed platform located on the continental shelf, a public place or private property likely to endanger human life or result in major economic loss; (e) seizure of aircraft, ships or other means of public or goods transport; (f) manufacture, possession, acquisition, transport, supply or use of weapons, explosives or of nuclear, biological or chemical weapons, as well as research into, and development of, biological and chemical weapons; (g) release of dangerous substances, or causing fires, floods or explosions the effect of which is to endanger human life; (h) interfering with or disrupting the supply of water, power or any other fundamental natural resource the effect of which is to endanger human life; (i) threatening to commit any of the acts listed in (a) to (h). |

[Part 5.3, Division 100.1 of the Criminal Code] terrorist act means an action or threat of action where: (a) the action falls within subsection (2) and does not fall within subsection (3); and (b) the action is done or the threat is made with the intention of advancing a political, religious or ideological cause; and (c) the action is done or the threat is made with the intention of: (i) coercing, or influencing by intimidation, the government of the Commonwealth or a State, Territory or foreign country, or of part of a State, Territory or foreign country; or (ii) intimidating the public or a section of the public. (2) Action falls within this subsection if it: (a) causes serious harm that is physical harm to a person; or (b) causes serious damage to property; or (c) causes a person’s death; or (d) endangers a person’s life, other than the life of the person taking the action; or (e) creates a serious risk to the health or safety of the public or a section of the public; or (f) seriously interferes with, seriously disrupts, or destroys, an electronic system including, but not limited to: (i) an information system; or (ii) a telecommunications system; or (iii) a financial system; or (iv) a system used for the delivery of essential government services; or (v) a system used for, or by, an essential public utility; or (vi) a system used for, or by, a transport system. (3) Action falls within this subsection if it: (a) is advocacy, protest, dissent or industrial action; and (b) is not intended: (i) to cause serious harm that is physical harm to a person; or (ii) to cause a person’s death; or (iii) to endanger the life of a person, other than the person taking the action; or (iv) to create a serious risk to the health or safety of the public or a section of the public.

|

Framework Decision 2002/475/JHA has since been superseded by Directive (EU) 2017/541 of the European Parliament and of the Council dated March 15, 2017, but the latter is mostly an updated version of the former

The definition of “critical infrastructure” in the proposed anti-terror law is almost identical to that in the Council of the European Union Directive 2008/114/EC. Another repealed Council of the European Union Framework Decision, 2008/919/JHA, expanded the EU legislative guidelines to include “recruitment for terrorism” as an act punishable by EU member-states.

Even earlier, the 2003 Australian law included “membership of a terrorist organisation” and “recruiting for a terrorist organisation” as offences. It seems Philippine legislators drew inspiration from both to define the new crime of “recruitment to and membership in a terrorist organization” (section 10). In the Australian law, to recruit “includes [to] induce, incite and encourage” and an offence is committed if a “person intentionally recruits a person to join, or participate in the activities of [a formally declared terrorist] organisation.” In the 2008 EU framework decision, “recruitment for terrorism” means “soliciting another person to commit” one of its listed offences. The proposed Philippine law says to “recruit” is to commit “any act to encourage other people to join a terrorist individual or organization, association or group of persons [formally proscribed as such under the Act] or designated by the United Nations Security Council as a terrorist organization, or organized for the purpose of engaging in terrorism”—a more overtly broad definition than the others mentioned.

Indeed, many critics of the proposed law have pointed out that several of its definitions, especially of terrorism, are vague, thus may lead to abuse. This may very well be because the definition appears partly adopted from an EU Council framework decision or directive, which are general enough to be tailor-fitted to an EU member-state’s legal system. The 2007 HSA is more similar to the way countries such as Belgium have implemented the 2002 Framework Decision and to US anti-terrorism laws because it mostly makes pre-existing crimes as predicate crimes for terrorism instead of defining completely new ones. Both bills filed by Senate President Tito Sotto and Senator Imee Marcos proposing to amend the 2007 HSA still anchored terrorist acts on crimes defined by existing laws. It was Senator Panfilo Lacson’s SB 21— largely a revival of a consolidated bill he principally authored during the 17th Congress—that contained the imported definitions mostly carried over to the consolidated bill, SB 1083.

There are indeed signs the consolidated bill rather thoughtlessly copied from other laws. For instance, the proposed law also considers it a terrorist act to organize or facilitate the travel of an individual to a foreign state for recruitment into or with an armed force in that country, as well as publishing advertisement or propaganda to recruit such persons. If these seem to penalize disloyalty to one’s country more than terrorist acts, it may be because these are near-identical to section 119.7 of Australia’s Criminal Code Act, which deals with recruiting persons to serve in or with an armed force in a foreign country, not terrorism.

The proposed measure also excludes kidnapping and hostage-taking as acts of terrorism. Considering how the Abu Sayyaf financed its operation through kidnap-for-ransom, mostly of foreigners, this seems to be an egregious exclusion.

Perhaps this absence is a product of mirroring the list of terrorist acts in Australia’s terrorism law, which does not explicitly mention abduction. But Australia has an additional qualification for crimes considered terrorist acts: the action (or threat to carry it out) must be done “with the intention of advancing a political, religious, or ideological cause.” There is no such qualification in the proposed Philippine law—one can have no particular political, religious, or ideological advocacy but still be considered a terrorist if all other relevant boxes in the law are checked.

Another cause for consternation is the grant of the power of designation (Section 25 of the proposed law) to the expanded executive group, the Anti-Terrorism Council, first created by the 2007 HSA. At first glance, this appears similar to the proscription (banning) section of the UK’s Terrorism Act 2000, as amended. The UK law gives the Secretary of State, “by order,” the power to designate a group as a terrorist organization. But in the UK law, there is a clear process for deproscription and further appeal. No such process is detailed in the proposed law.

The power to designate in the anti-terrorism bill also seems similar to the listing power in relevant Australian provisions, though the latter seems more stringent. It is the Australian Governor-General who issues a regulation to list a terrorist organization as such but only after the Minister of Home Affairs is “satisfied on reasonable grounds” that the organization is identified or referred to in a decision of the Security Council of the United Nations “relating wholly or partly to terrorism” and “is directly or indirectly engaged in preparing, planning, assisting in or fostering the doing of a terrorist act (whether or not the terrorist act has occurred or will occur).”

In the proposed law, however, it seems clear that the ATC’s designation power should be seen as limited in purpose. Under the proscription process detailed in section 26, before any legal action can be taken against an organization, the ATC has to authorize the Department of Justice to apply for an order of proscription from the Court of Appeals. One has to be a member or recruit members for a formally proscribed organization to be charged with recruitment to and membership in a terrorist organization. However, the proposed law allows the CA to issue a preliminary order of proscription within 72 hours of application upon a finding that doing so is “necessary to prevent the commission of terrorism.” The preliminary order effectively proscribes an organization for up to six months, within which the Court will decide if it should be permanently banned.

What will designation do? Section 25 of the proposed law will address a specific problem in the implementation of the Terrorism Financing Prevention and Suppression Act. In 2017, Duterte issued Proclamation No. 374, “Declaring the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP)-New People’s Army (NPA) as a Designated/Identified Terrorist Organization under Republic Act No. 10168.” As has been pointed out several times, even by Roque, this had no domestic legal effect since the CPP-NPA still had to be declared a terrorist organization by court order for any of the provisions in RA 10168 to apply. Only the Abu Sayyaf group was declared a terrorist organization under the HSA of 2007. To date, no Philippine court has proscribed the CPP-NPA.

The Anti-Terrorism Act can “cure” this “defect.” If the proposed law’s provisions are strictly construed, the AMLC may investigate, inquire and examine the bank deposits of a group designated as a terrorist organization or its members and those believed to be financing it. AMLC may also freeze such funds or assets for a limited time. The ATC should not be able to use Section 25 to designate any organization a terrorist organization to round up and arrest their members. It can cite the provision to speedily cut off a person or organization from their money or property, and to collect evidence that may eventually be used for an application for an order of proscription. The term “fishing expedition” immediately comes to mind. Given how the present dispensation has weaponized the law to take down its political opponents and critics, there is not much confidence the ATC will be able to resist the corrupting influence of political kingpins.

Perhaps even more frightening is ATC’s role in the detention without judicial warrant of arrest of persons suspected of committing acts of terrorism. Under section 29 of the proposed law, the ATC’s authorization is necessary for such warrantless arrests. One is hard-pressed to find any Philippine law still in effect that allows an arrest based on mere suspicion of committing a crime. What comes to mind is the long-repealed Presidential Decree 1877. Under this 1983 decree, Ferdinand Marcos had the authority to issue “preventive detention actions” to indefinitely detain people without arrest warrants or charges because they are committing or are about to commit insurrection, rebellion, subversion or related offenses that endanger public order and stability.

Under the 2020 Anti-Terrorism Act, similar detention is limited initially up to 14 calendar days, extendable up to 10 days. Imagine the described initial detention being used in combination with Section 25’s designation, which, to recap, allows freezing and investigation of assets. Again, one can imagine fishing expeditions of greater frequency and effectiveness. Formal charging and proscription can follow soon after.

In the UK, Terrorism Act 2006 allows terrorist suspects to be detained without charge for up to 28 days. If this inspired the 24-day detention in the proposed Philippine anti-terror law, it should be pointed out that according to Human Rights Watch, based on the UK’s Home Office report, 669 out of 1,228 persons—over 50 percent—of those arrested in terrorism investigations between Sept. 11, 2001 and March 31, 2007 were released without charge.

And why have states such as the UK and the US been able to use their anti-terrorism laws to such terrible effect, while the Philippines with its HSA has not? Law enforcers point to the 2007 HSA’s safeguards against abuse in the law, including hefty damages for persons whose assets were seized but are eventually cleared of terrorism. The new law simply hacks off such safeguards.

Going back to the ATC, none of the original three Senate proponents of the anti-terror law proposed elevating the National Security Adviser, previously only a member of the Council, to ATC vice chairperson. This was an amendment introduced after the bill’s consolidation and before its passage on third reading at the Senate. The three additional authors of the consolidated bill are Senators Lito Lapid, Bong Revilla Jr., and Ronald dela Rosa.

The country’s current National Security Adviser is Hermogenes Esperon, who also happens to be the vice chair of the National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC). The NTF-ELCAC has recently released names of mass organizations allegedly established by the CPP-NPA-NDF. It is not difficult to imagine who the reorganized ATC may go after first once the Anti-Terrorism Act will be fully in effect.

Since its formation on December 4, 2018, NTF-ELCAC has referred to the CPP-NPA-NDF as “Communist Terrorist Group,” with the added justification that they are called such by the United Kingdom, the European Union, the United States, Australia, Canada, and New Zealand.

As Senator Lacson admitted in a June 4, 2020 press statement, he “incorporated most of the provisions of the Anti-Terrorism laws of other strong democracies like Australia and the United States, further guided by the standards set by the United Nations” in the anti-terror bill. He conveniently left out that even in said “strong democracies,” anti-terrorism measures have instantiated time and again acts of inhumanity, especially to those considered “foreign” to the constitution of the nation.

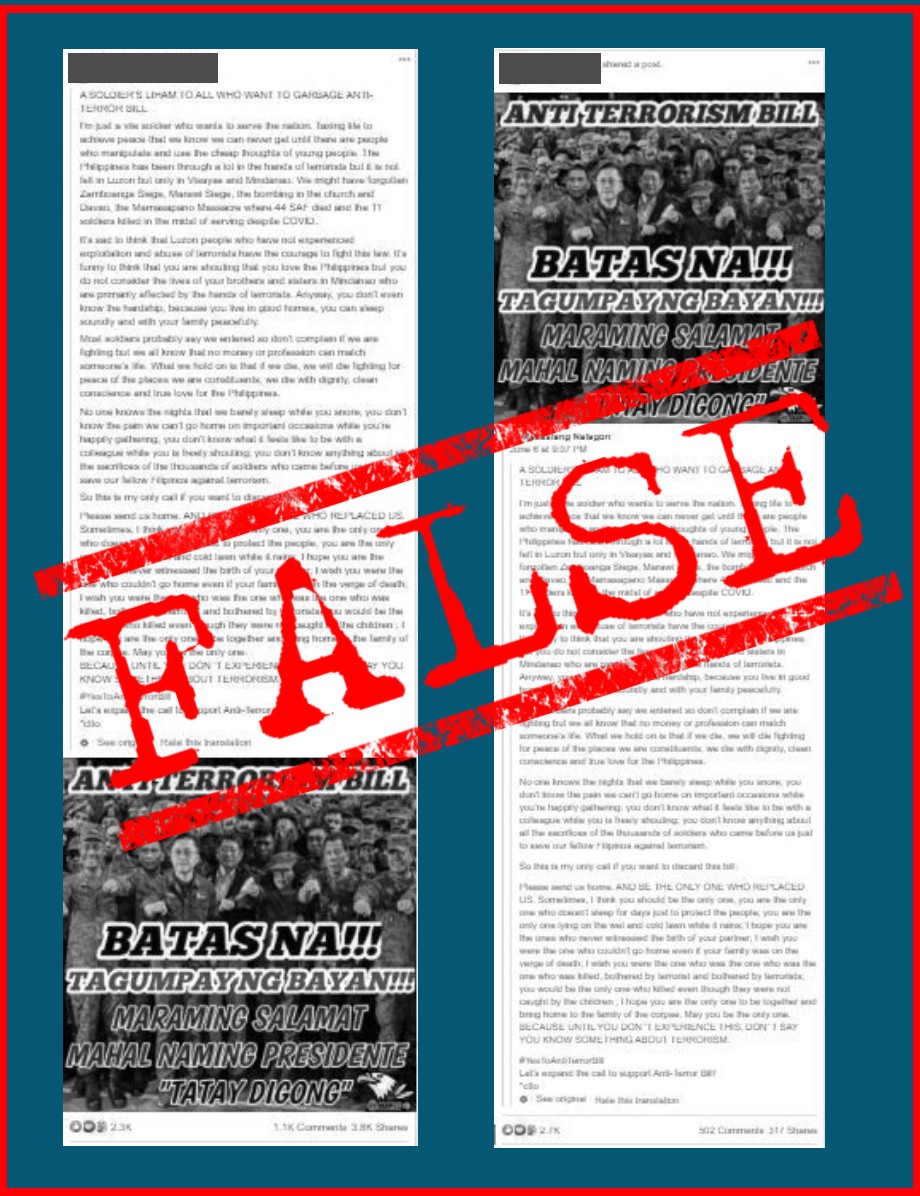

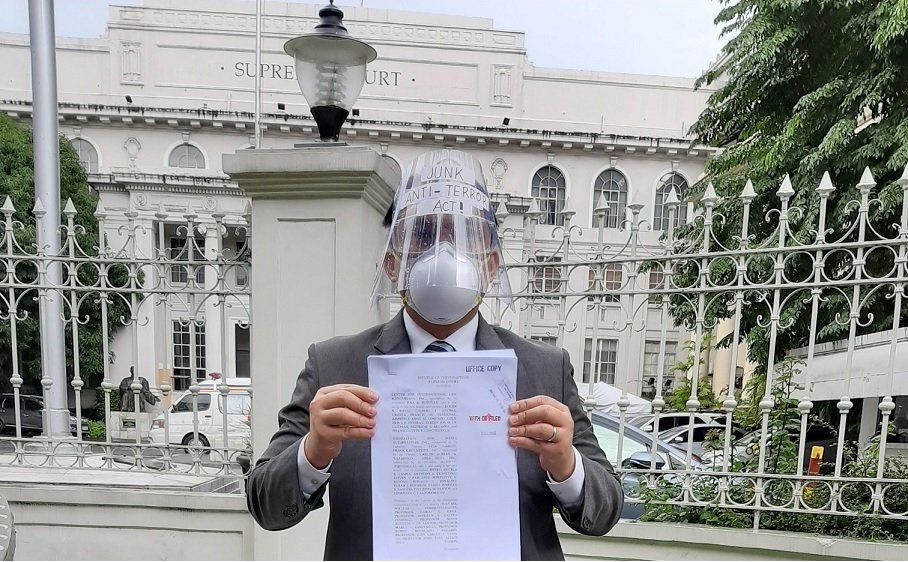

Various groups have been fighting the passage of the Anti-Terrorism Act, which they see as an attack against their advocacy work as well as the civil liberties of the ordinary citizen. But the hearts and minds of the ordinary citizen have become receptacles of both disinformation and disenchantment. The protests have been instigated and sustained by many, but they have also been derided and condemned by a cult that believes the imposition of martial measures is the quick and easy answer to everything — that is, until they themselves become the target.

“It is going back to the days of disquiet and nights of rage,” forewarns the National Union of People’s Lawyers. Senator Lacson dismisses these protests and opposition as nothing but a “massive disinformation campaign.”

(Miguel Paolo P. Reyes, Joel F. Ariate Jr., and Elinor May K. Cruz are researchers at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman)