Barely a year old, the Department of Health’s quit line program has helped a number of citizens lead tobacco-free lives. It should aim for many more.

A quit line or “quitline” is a telephone counseling service for people who want to stop smoking. It can provide smokers who need help but are reluctant to undergo face-to-face counseling.

Much evidence from around the globe shows that quit lines do work. Inspiring stories have come from the experiences of Australia, Brazil, New Zealand, Singapore, Sweden, Thailand, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

The DOH quit line program consists of four numbers:

- A landline, 165364 followed by 3, can be called by landline users in Metro Manila for free.

- Two mobile numbers, (0921) 203 9534 (Smart/TNT/Sun) and (0977) 627 7539 (Globe/TM), can be accessed by cellphone users. Unless they enjoy unlimited calls, though, the usual charges will apply.

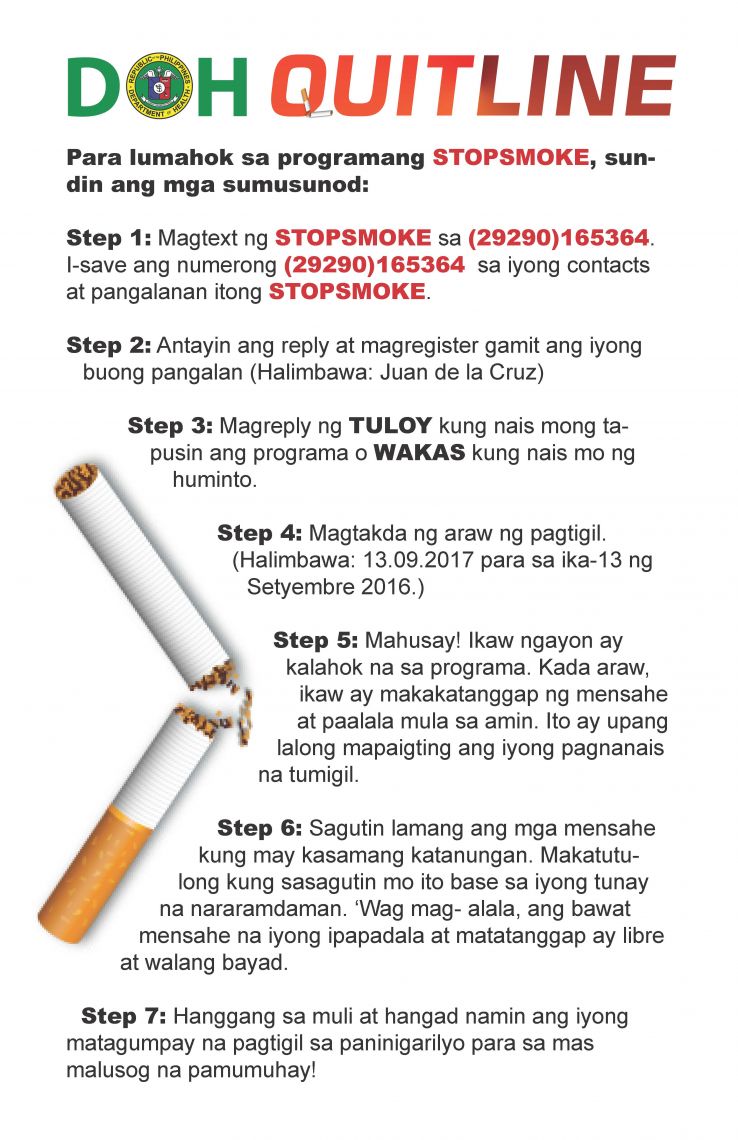

- mCessation is a text-based messaging service. To enroll in the service, smokers need to have at least ₱1 load to text “STOPSMOKE” to (29290) 165364. Once subscribed, they will receive, free of charge, daily messages that will guide them to quit smoking.

But many issues hamstring the program. For one, the six-digit landline, which is at the DOH office in Manila, is hard to reach.

Warren Nombre is a security guard stationed in Makati City. He did not get through the line when he called it last January.“That’s why I called their cellphone,” he said. “From then on, the counselors called me on my mobile phone.”

Nombre hid his cigarette habit from his family for about 12 years. Chain smoking kept him awake when he was on the night shift but the habit took its toll on his health. He got breathless after short walks and suffered from insomnia. His weight ballooned to 75 kilos, and his blood pressure shot up.

Nombre wanted help badly. But he works 12 hours a day and could not seek free counseling at the smoking cessation clinic at the Ospital ng Makati, just a stone’s throw away from his workplace. The quit line service was a game changer for him.

Nombre is one of the 31 Filipinos who have benefitted from the DOH quit line. Since January, he has been tobacco-free. His weight is down to 68 kilos, he sleeps better and he has started jogging, too.

The program can help more people, though, if the kinks in it are ironed out. Then it can become a true game changer.

Nicotine addiction hard to overcome

In the Philippines, 22.7% of adults smoke tobacco, according to the 2015 Global Adult Tobacco Survey. This means that 15.9 million people aged 15 years and above are hooked on nicotine.

“Up to half of all tobacco users will die from a tobacco-related disease,” says World Health Organization in a report. These deaths take a heavy toll on society. In 2003, WHO estimated the economic cost of smoking-related diseases in the country at a whopping $6 billion. This figure includes healthcare and lost productivity costs. It amounted to over 7% of the GDP that year.

The 2015 survey shows that seven out of 10 smokers, or 76.7%, want to quit. This is a big jump from 60.4% in 2009. And more smokers are trying to quit: In 2009, 47.9% of smokers made quit attempts over a 12-month period. In 2015, that percentage went up to 52.2%.

But smoking is a hard habit to break. In 2009, the proportion of smokers who successfully quit among those who attempted was 4.5%. In 2015, it had gone down to 4.0%.

It’s tough to quit smoking cold turkey. Of daily smokers who try to quit unaided, only 5–10% will succeed, reports WHO.

The good news is that quit lines greatly increase quit rates, according to the U.S. Public Health Service guideline, Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. This body of research paved the way for the expansion of quit line services throughout the U.S. A single tollfree number (1-800-QUIT-NOW) now serves as a portal to state-based quit lines.

Among the evidence cited in the guideline is a 2008 meta-analysis comparing the estimated abstinence rates for quit line counseling compared to minimal interventions, self-help, or no counseling. The study found that quit lines produce an estimated abstinence rate of 12.7%. The other interventions result in an estimated abstinence rate of 8.5%.

Many smokers worldwide need help to overcome their nicotine addiction. Article 14 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) mandates all its parties to “take effective measures to promote the cessation of tobacco use and adequate treatment for tobacco dependence.” These measures include easily accessible and free quit lines.

The Philippines became a party to the WHO FCTC on September 4, 2005. The guidelines for implementing Article 14 of the WHO FCTC recommend that: “All Parties should offer quitlines in which callers can receive advice from trained cessation specialists. Ideally they should be free and offer proactive support. Quitlines should be widely publicized and advertised, and adequately staffed, to ensure that tobacco users can always receive individual support. Parties are encouraged to include the quitline number on tobacco product packaging.”

Part of the quit line’s budget comes from tobacco sin taxes, which are considered a win for health care. Within six years of passing the sin tax law, the 2018 budget of the DOH—₱160.7 billion—is almost four times its 2012 budget of ₱42.2 billion.

There is no way of knowing, though, just how much of the quit line budget came from sin taxes, said Dr. Ma. Cristina Galang, a medical specialist IV at the disease prevention and control bureau of the DOH.

The Lung Center of the Philippines hosts and manages the quit line in coordination with the DOH disease and prevention control bureau-degenerative disease office.

Initially, the quit line consisted of a landline and mCessation. Shortly after the launch, two mobile numbers for inbound and outbound calls were added.

What went right

How has the DOH quit line helped tobacco users and the community? Here are four ways.

- Callers receive free advice from trained counselors.

- Counselors proactively support tobacco users.

- The quit line adds to the efforts of health professionals to treat tobacco dependence.

- The quit line has served as a resource on other community services.

At the DOH quit line, six specially trained counselors man the fort. They are guided by the Prochaska and DiClemente Stages of Change model. This model “offers a framework for understanding the incremental processes that people pass through as they change a particular behavior.” It is modeled in five stages: pre-contemplation (not ready to change); contemplation (thinking of changing); preparation (ready to change); action (making change); and maintenance (staying on track).

The counselors find out which stage of change the caller is in. Then they can tailor motivational strategies to the needs of a person in that stage.

For example, data shows that 99 of the 204 people who sought counseling from the quit line—48.5%—are in the preparation stage. They plan to act within one month. Nombre was one such person. The date he called the quit line was his quit date.

The counselors are taught “the theories of smoking cessation, benefits of quitting, call handling, motivational interviewing, and the 5As of counseling,” said Roberto Garcia Jr., who manages the quit line’s operations.

This the framework proposed in the U.S. Public Health Service guideline. It helps the counselors work one-on-one with callers to help them identify barriers to quitting, create a quit plan, and overcome urges.

The counselors Ask the caller about his or her tobacco use, personal details, and medical history. They use the data to Advise the caller in a personalized manner to quit for health, family, social, and financial reasons. They Assess the tobacco user’s willingness to quit. The counselors then Assist him or her in setting a quit date and provide counseling support. Lastly, they Arrange follow-up calls. These calls are scheduled by agreement with the smoker.

They counselors spend an average of 20 minutes for the first session. Then each follow-up call takes an average of five minutes.

They make follow-up phone calls to check on callers’ progress and provide encouragement. Data gathered from June 19, 2017 to April 30, 2018 shows that outbound calls accounted for 81.1%, or 1,951 calls. Only 18.8%, or 452 calls, or were inbound calls.

“After a caller has set a quit date, our protocol is to call 24 hours before the date, on the date itself, then 24 hours, 48 hours, and 72 hours after the date,” said a counselor named Nonat (not the real name). “We want them to feel our constant presence as counselors.”

They don’t stop there. The counselors make weekly follow-ups for three weeks after the quit date, then monthly calls for five months after the date.

Should a caller relapse, the counselors encourage him or her to try again. “We don’t say ‘you have suffered a relapse,’” Nonat said. “Instead we say, ‘let us continue,’ to encourage them to quit.”

Proactive follow-up calls enhance the effectiveness of a quit line. A 2013 Cochrane review found that “Three or more calls increase the chances of quitting compared to a minimal intervention such as providing standard self-help materials, or brief advice, or compared to pharmacotherapy alone.”

The strategy has paid off. As of April 30, 2018, 204 people—162 males and 42 females—have received counseling from the quit line. Of these, 31 people—24 males and 7 females—have quit smoking. This shows a quit rate of 15.1%, which is about five times more than the quit rate of 2-3% resulting from brief advice, according to the WHO, which defines ‘brief advice’ as three to five minutes of smoking cessation advice.

After WHO topped up the load, mCessation came back on in February 2018. As of April 30, 2018, 3,241 people have enrolled in the service.

Doctors like Dr. Glynna Ong-Cabrera from the Lung Center of the Philippines, welcome the quit line. It complements the counseling that they do when they see patients in their clinics.

“The actual talking to the person will take 30 to 40 minutes at least,” said Dr. Cabrera. “Doctors cannot give that much time, especially if they have a lot of patients.” Aside from being the program manager of the DOH quit line, she is also the director of the smoking cessation program at the Lung Center.

Since the quit line opened in June 2017, 247 people, or 54.7% of all callers, called to make inquiries. Many were concerned about loved ones who smoked. Some were smokers who were worried about withdrawal symptoms.

The quit line counselors also refer callers to the smoking cessation clinic nearest them. As of March 28, 2018, they have referred 26 callers to various clinics.

What went wrong

Many issues hamper the effectiveness of the DOH quit line. The quit line landline and mobile numbers are not toll-free. Also, mCessation failed to takeoff.

Quit lines are more effective when there are no financial barriers to access. “Requiring the tobacco user to pay, even partially, for counselling, regardless of the setting, has generally proven to be a major impediment to utilization, even in high-income countries,” states WHO in its manual.

This is likely to be even more the case for quit lines in low-income countries like the Philippines. According to the 2015 Global Adult Tobacco Survey, majority of the daily smokers in the country belong to the two lowest quintiles.

Having toll-free numbers would make the quit line accessible to all tobacco users in the country. At the moment, though, calling the landline to talk to a live counselor is free only for callers in the megacity. Long-distance charges apply to calls made from outside Metro Manila. This prompted one netizen, Virgo Eidref Ferdie, to comment on the DOH Facebook page: “Free for callers from metro manila only? Ang bait!panay manila lang ang libre!”

The lack of toll-free numbers has limited the quit line’s reach to mainly the megacity. Of the 204 people who sought counseling, 142 people or 69.6%, called from Metro Manila.

Outside of Metro Manila, 58 people, or 28.4%, received counseling from the quit line. The lion’s share of callers came from Luzon and only a handful of smokers in the Visayas and Mindanao were served by the quit line.

Why was the six-digit landline used when it is not toll-free? “Given the short notice, we had to make do with that interim number since it’s readily available,” said Emily Razal, information technology officer at the DOH knowledge management and information technology service.

Razal began work on the quit line program in February 2017, merely four months before its launch. Her office revised the DOH trunk line interactive voice response in Manila so that the public could call the quit line.

“Our IT people are working on a strategy that will make the calls free,” said Dr. Cabrera, without specifying a timeframe.

What is practically free for tobacco users is mCessation. To enroll, smokers need to have at least ₱1 load to text “STOPSMOKE” to (29290) 165364 and to subscribe to the service. Once subscribed, they will receive, free of charge, daily messages.

mCessation has much potential to help millions of cellphone-toting Filipinos who smoke. In 2016, there were 109.17 mobile cellular subscriptions for every 100 people in the country.

The program is off to a bumpy start, though. mCessation only worked from June 2017 to October 2017 or until the load lasted. It was out of commission for three months.

What happened?

Razal said that it was WHO that contracted Voyager Innovations to manage mCessation. Therefore, she could not contact Voyager directly. She said that it seems that a change of personnel in both organizations led to a miscommunication that led to the nonpayment of the load needed to run the service.

WHO’s funding of mCessation is just a stopgap measure, however. The Philippine government should be financially committed to the project to own it and have a stake in its success.

However, procurement has been problematic. The DOH has invited public bids for the “Hiring of a Service Provider for the DOH mHealth / mCessation SMS Service.” It has a budget of ₱2 million for the 14-month contract. To date, there have been no takers in four failed bids: three last year and one this year.

An IT expert familiar with the government’s procurement process opined that the budget may be too low to attract the private sector.

Another barrier that mCessation faces is the low educational attainment of smokers in the Philippines. Nearly half of the daily smokers either have no formal education or have completed at most an elementary school education. They would therefore have a hard time completing the seven-step process needed to successfully enroll in mCessation.

This has been a problem. “Someone texts ‘STOPSMOKER’ when it should be ‘STOPSMOKE,’” said Mary, a counselor. “The registration will not proceed.”She and the other counselors monitor the mCessation dashboard in real time. To help the smoker, they text him or her what the correct message should be. “If we relied on the app alone, that might fail so that would be a waste,” she said.

• It doesn’t help either that the quit line landline, mobile numbers, and mCessation are not widely publicized and advertised. “For a new quit line, a rule of thumb is to allocate at least one US dollar for quit-line operations for every US dollar spent on promotion,” states WHO in its manual.

But the quit line’s budget of ₱27 million is for “program support to the Lung Center of the Philippines for the establishment and implementation of quit line and mCessation,” said Dr. Galang. The budget includes: “human resources augmentation of quit line (salaries); operating expenses; trainings; promotion/marketing; and technology.”

Promotion is a challenge, Garcia admits. But they also cannot promote the landline and mobile numbers because the numbers are not toll-free.

Instead, the DOH quit line has relied on earned media: news stories featured on television or radio, in newspapers or magazines, or on websites. And Dr. Cabrera has guested on TV shows to promote the quit line.

“That works,” said Garcia. “When we ask people how they found out about quit line, they say that they saw it on TV.” Data shows that TV is the top source of information about the quit line; 81 people—39.7% of the callers who’ve sought counseling—learned about the program through broadcast media.

They have not launched any mass media campaign, though. Such a campaign often results in an immediate increase in calls to a quit line.

Garcia asked a chicken-and-egg question. “If we promote the quit line and get many calls, can we take all the calls, given the limited resources?”

He enumerated the realities:

•The quit line barely has enough staff.

Initially, the plan was to have 21 quit line counselors providing 24/7 service. At the moment, though, six counselors work in two shifts: 7 a.m. to 10 p.m., Mondays to Fridays, and 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. on Saturdays.

Why the downscaled operations? After the launch in June 2017, the number of callers dwindled, said Garcia. It made sense to shorten operating hours, which took effect on December 1, 2017.

What happens to the calls received after the quit line’s work hours? “We let the call center of the Lung Center pick up the calls (after 10 pm),” Garcia said. “We trained them how to get the name and contact number of the callers so that we can call them the next working day.” If callers need counseling right away, they are passed on to the pulmonology fellows on duty, he said.

•Until recently, the quit line counselors lacked office equipment.

The counselors each have an Internet phone to use. Shortly after the quit line was launched, they saw the need for two mobile phones for making follow-up calls. So they started using two of their personal mobile phones using different SIM cards. On April 3, 2018, the counsellors were issued two new mobile phones for their official use.

They used to share three computers that were borrowed from the Lung Center. The DOH granted their request for three laptops, six desktop computers, and a printer on March 6, 2018.

Wanted: a robust quit line program

The DOH quit line has much going for it. The program is based on the best evidence. Its counselors are trained to proactively support callers. Funding is not an issue.

Barely a year after it was launched, the program has achieved a 15.1% quit rate. This quit rate is “quite good,” said Dr. Ulysses Dorotheo, project director at Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance. “It could be much better if the service were available 24 hours and if it were toll-free,” he said.

It is high time the DOH went back to the drawing board to review WHO’s technical advice for establishing and operating quit-line services: “It is essential to determine:

- an individual who will become the quit-line expert

- the needs for quit-line services in the population

- the place, role, and goals of the quit line in national tobacco control

- the range of services, likely utilization, and strategies for creating demand

- the sponsors that could fund and oversee the quit line

- minimal standards and a project management plan

- how to ensure that the quit line is adopted, implemented and maintained

- the organization that will deliver the services and the individual who is accountable for ensuring its success.”

Finding a champion for the DOH quit line will help improve the program. At the moment, no single individual is out there advocating for it. But imperfect as it is, the quit line has already helped people like Warren Nombre.

As the WHO says in a report, such a service starts to create an enabling environment for smokers. It “provides tangible evidence that society wants to help them quit, not punish and stigmatize them.”

(This story was produced under the “MgaNagbababangKuwento: Reporting on Tobacco and Sin Tax Media Training and Fellowship Program” by Probe Media Foundation.)