Fifty-seven years ago, on January 11, 1964, a Saturday, then-US Surgeon General Luther L. Terry, MD, released the first-ever report on the ill effects of tobacco smoking on health. Drawing from over 7,000 biomedical articles and enlisting the help of more than a hundred experts, the 1964 report concluded that smoking was, in no uncertain terms, a top cause of lung cancer in men (and a probable cause in women), and of chronic bronchitis in both sexes.

At the time, Terry made it a point to release the report on a Saturday, so as not to perturb the country’s stock market too much, and in hopes that its findings would slip by unnoticed by the Sunday news cycle. He couldn’t have been more wrong. Years later, Terry still remembers that the report “hit the country like a bombshell. It was front page news and a lead story on every radio and television station in the United States and many abroad.”

Experts and advocates hoped that the 1964 report would mark the start of a cultural shift away from tobacco but today, more than five decades since, what was once an explosive revelation has been neutered into a barely audible pop, drowned out by the industry’s cacophony of marketing and misinformation.

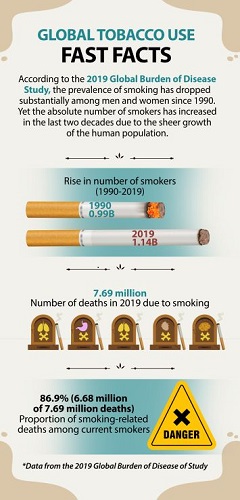

According to the 2019 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) survey, published in the medical journal The Lancet, more than one billion people remain active smokers. Though there has indeed been a notable decline in the percentage of smokers since 1990, efforts to curb smoking have been outpaced by population growth. There were 150 million more smokers in 2019 than in 1990.

If everyone knows that smoking kills, why are tobacco products still legal? Why are these products, and the industry that peddles them, so loosely regulated? Why has the US Surgeon General’s first warning in 1964 gone unheeded?

And, more important to the times we live in: Why are governments the world over working overtime to address the COVID-19 pandemic that has killed 3.79 million people in the past 18 months, but are tolerating and seemingly neglecting the tobacco pandemic that kills 8.2 million people every year?

The challenge of quitting tobacco

At the start of the 20th century, lung cancer was an incredibly rare disease, so much so that medical students were told that they might never see one in their lifetime. But advancements in technology have meant that from rolling three to five sticks by hand per minute, productivity jumped to some 200 cigarettes per minute. Today’s machines produce 20,000 death sticks per minute.

An inflated supply dragged demand upward along with it, and tobacco addiction ballooned not long after. By the mid-1960s, as Terry was in the process of writing his report, up to 70 percent of the population were smokers in the US and in some European countries.

Health advocates conduct a lie-in protest calling for more stringent tobacco regulation in Manila, Philippines, where smoking claims 12 lives per hour. (Photo from the Youth for Sin Tax Movement)

Eventually, as smoking declined in the West, transnational tobacco companies exploited trade liberalization, foreign direct investments, technological innovation, global communications, and other facets of a globalized economy to establish and expand markets in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), which now comprise 80 percent of all tobacco users and deaths. Incidentally, two-thirds of the world’s smokers live in just 10 countries, many of which are from Asia, including the Philippines, China, India, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Japan, and Vietnam.

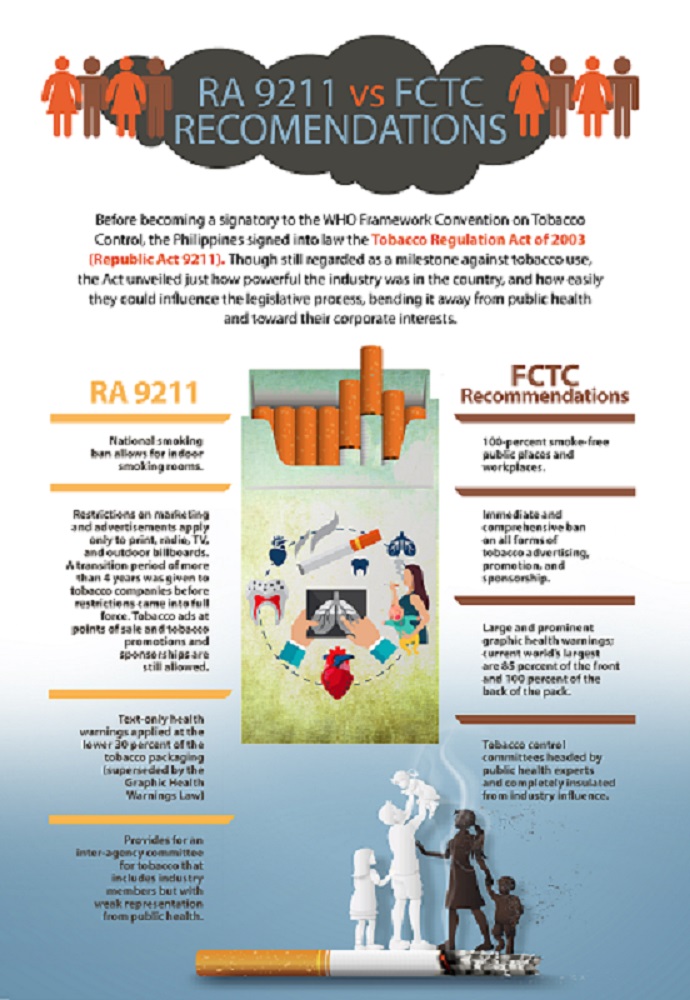

Responding to this globalization of the tobacco epidemic, World Health Organization (WHO) member states negotiated and approved the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), which entered into force in 2005, spanning 182 State Parties, all obligated to implement its provisions.

In particular, the FCTC provides a clear roadmap of demand and supply reduction measures, based on scientific evidence and international best practices, to help countries effectively and continually reduce tobacco use and exposure, in order “to protect present and future generations from the devastating health, social, environmental and economic consequences of tobacco consumption and exposure to tobacco smoke.” Governments simply have to follow through on their commitments and implement their treaty obligations, something that has always been easier said than done.

For the most part, Parties to the FCTC have focused on reducing the demand for tobacco, but even that has been problematic, with many national and local governments implementing differing degrees of regulation. For example, taxation is widely recognized as one of the most effective tobacco control policies, but cigarettes are significantly cheaper in LMICs compared to high-income countries.

Other measures—such as bans on advertising, promotion, and sponsorships, laws on packaging and health warnings, designation of smoke-free zones, and strict regulations on the products themselves – have likewise been applied unevenly across FCTC Parties.

In their implementation reports to the WHO FCTC Conference of Parties, governments enumerate the roadblocks to fulfilling their commitments to the Convention. Challenges, according to these reports, are plentiful but shared: limited human and financial resources, weak legislation and enforcement mechanisms, insufficient political support, and weak intersectoral coordination. But across the board, countries agree that industry interference—corporate meddling into all levels of law making and execution—is their most pressing problem.

After all, as with other health crises, weak health systems and governance impede effective response, but unlike viruses and parasites that do not have an industry to promote their spread (i.e., no malaria industry, just mosquitoes that need to be controlled and eliminated), some public health problems, such as tobacco, alcohol, and unhealthy food, have commercial entities driving them. These are often referred to as negative commercial determinants of health because of their interference in public health policy development and implementation. This is why, despite knowing what works and what needs to be done, tobacco control progress has been haltingly slow.

Friends in high places

In 2012, some seven years after the country signed the FCTC, the Philippines finally passed its Sin Tax Reform Law. This law has since been touted internationally as among the most progressive in the world in terms of levies imposed on tobacco products. Buoyed by this success, the Philippines passed its Graphic Health Warning (GHW) Law two years later, in 2014.

But neither legal milestone was achieved without much opposition from the industry. Ultimately, the corporations were given their concessions, and what passed into law were watered-down versions of their proposals. The Sin Tax Reform Law, for example, had much lower excise tax rates than what had originally been proposed, and provided a 5-year transition period of tiered taxation before applying a unitary rate for all brands.

The Philippines has a long history of tobacco industry interference dating back several decades. Over the years, representatives of tobacco companies have fostered tight and enduring relationships with many of the country’s notable political personalities, at every level of the political ladder.

Dr Ulysses Dorotheo at a public demonstration in 2019, calling for higher taxes on tobacco products. The Philippine government passed the Sin Tax Reform Law in 2012, which imposed greater levies on cigarettes. Though the Law is touted internationally as a good tobacco control measure, strong industry interference watered it down compared to the original proposal. (Photo from the Youth for Sin Tax Movement)

In late 2016, just weeks before the Sin Tax Reform Law’s tiered transition period was set to lapse, industry allies in Congress filed a bill seeking to retain a two-tiered tax structure, completely doing away with the legislated unitary rate.

Whereas the Sin Tax Reform Law took more than a year of congressional deliberations—even with the full support of the Departments of Finance, Health, and other government agencies—this new industry-backed bill was approved by the House committee after only two hearings seven days apart, and subsequently approved in plenary eight days later. Fortunately, the Senate failed to act on the industry-friendly bill, which meant that the unitary tax scheme did eventually come into effect.

More recently, industry representatives have worked to normalize their supposed harm reduction products. Amid a strong push by pro-health senators to hike tax rates on tobacco products, pro-industry lawmakers were able to sneak in a last-minute provision, taxing heated tobacco products (HTPs) and e-cigarette e-liquids at very much lower rates.

In this way, the industry was able to legitimize HTPs and electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS, such as e-cigarettes) in the country. Pro-health legislators pushed back by proposing that HTPs and ENDS be required to carry GHWs and be prohibited for sale to non-smokers and those below 21 years old, and this was approved, but clearly, it isn’t enough. Instead, there is still a need to raise the tax rates on these new products.

This—new nicotine delivery products such as ENDS and HTPs—has become the new battleground for pro-industry lobbyists and pro-health advocates. Unsurprisingly, the industry is aggressively pushing to weaken the current regulatory policy for HTPs and ENDS. In 2019, the industry got a court injunction to stop the government from implementing regulations on HTPs and ENDS.

In May 2021, pro-industry legislators succeeded in passing a bill in the Lower House which, while it pretends to regulate the industry, only expands access to these alternative products by reversing the current law, bringing down the minimum age from 21 to 18 years and allowing multiple flavors and online marketing and sales. A counterpart in the Senate has also been penned and supported by pro-industry senators and is currently undergoing interpellation.

As it did with light and low-tar cigarettes, we are seeing the industry spreading misinformation with its claims that it is part of the solution to the tobacco pandemic by offering reportedly less harmful alternatives.

The industry has only dressed up its usual tricks in shiny new electronic clothes. It is hijacking the political and legislative process, exaggerating its economic importance, manipulating public opinion (including through journalists and columnists) to focus away from the health, socio-economic, and environmental harms it causes, creating and supporting astroturf front groups that focus on “rights” to use the industry’s products, funding biased research in favor of its products while discrediting other research that proves their harmfulness, and intimidating governments with litigation.

Eyes on the tobacco endgame

Fortunately, there are examples of various governments having resisted the meddling of the tobacco industry, which other governments—of the Philippines or otherwise—can look to for guidance.

Australia, for example, established a National Preventative Health Taskforce in mid-2009 to develop “a comprehensive and lasting Preventative Health Strategy,” which included among its targets the burden of chronic diseases caused by tobacco and other lifestyle factors.

Among the Taskforce’s recommendations to government was plain tobacco packaging, which Australia subsequently legislated and in 2012 implemented. Plain packaging helps eliminate one of the industry’s main (and sometimes last) avenues of marketing, effectively denormalizing tobacco use.

Of course, this move was fiercely opposed by the industry both in Australian courts and through international trade and investment disputes. But the government expected this and was prepared: they enlisted robust technical and legal support, buttressing strong political leadership at all levels and departments of the government. They ultimately won.

Such a whole-of-government, and whole-of-society, approach has been identified as an essential mark of initiatives that successfully address the huge and growing burden of non-communicable diseases. Countries like the Philippines, where the industry can comfortably flex its interference muscles, have achieved this more than once, with the landmark Sin Tax Reform and GHW Laws. But proponents of tobacco are strong and their pockets are unimaginably deep. The tobacco control campaign road remains long and tough.

Fortunately, as health advocates, we know that achieving a tobacco-free future is not a sprint but a marathon. Tobacco industry interference is expected, but there will always be people who believe in truth and social justice, who will fight this good fight, hopeful that in the end, good will triumph over evil. The devastating toll of tobacco on individuals and society, the willful deception of the public by the tobacco industry, and our love for humankind compel us.

Dr. Ulysses Dorotheo is a Filipino neuro-ophthalmologist and tobacco control advocate with more than 25 years of experience in patient care, education, and advocacy for both communicable and non-communicable diseases. Currently, he is the Executive Director of the Southeast Asia Tobacco Control Alliance (SEATCA) and a member of the WHO Civil Society Working Group on Non-Communicable Diseases (NCDs) and the World Heart Federation Tobacco Experts Group.

This story is produced under the Nagbabagang Kuwento (Burning Stories) Tobacco Control Media Program of the Probe Media Foundation Inc. supported by the Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids.

Note: a condensed version of this piece was first published on Aug 10, 2021, in the Asia Democracy Chronicles. Read it here.

The original version of this story can also be found on Dr. Dorotheo’s blogsite.