GUBAT, Sorsogon — In this town’s coastal villages, where mangrove forests meet the Pacific, crab farming has long been both a household livelihood and a reflection of the community’s relationship with the sea. Their work is both a tradition and an evolving response to environmental change.

Today, shifting weather patterns, changing shorelines and fluctuating markets are challenging that livelihood, yet they are also prompting innovations, collaborations and new conversations on how coastal communities can sustain both people and nature.

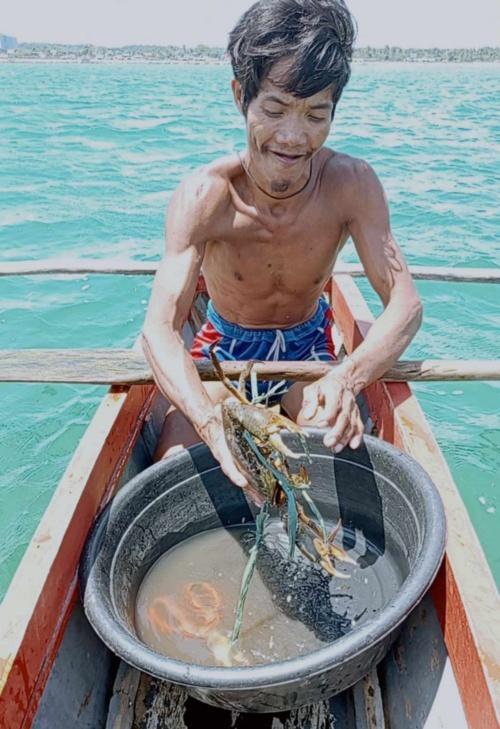

For small-scale crab growers like Salvador Fidellaga, 48, the work begins with 1,000 tiny megalopa—delicate larvae caught from the shorelines. Only about half survive their month-long stay in brackish-water nurseries, yet those 500 coin-sized crablets provide income, hope and continuity for his family and for dozens of others in Barangay Cota na Daco.

The town of Gubat is one of Bicol Region’s key sources of wild-caught mangrove crab stock (Scylla serrata), supplying crablets to aquaculture operators across the Philippines. Yet the work has become more challenging. The cost of feed, shifting weather patterns, lower market prices and the changing health of coastal ecosystems are shaping a new reality for crab farmers.

But crab farmers are increasingly aware that their success depends not only on their ponds and feed but on the health of the mangroves, the stability of tidal flows and the policies that shape coastal development.

A livelihood adapting to change

A decade ago, Fidellaga could earn nearly ₱50,000 per harvest in his rented 3×40 meter pond. Today, earnings average around ₱10,000. Rising feed costs, lower market prices and unpredictable seasons have tightened margins. Feeding alone costs at least ₱4,200 per month, for four rounds of high-protein feed needed to help the megalopa grow.

Despite these pressures, he and many others continue to farm, driven by a knowledge passed down over generations and strengthened by community networks.

During peak months from December to April, catcher and nursery operator Ernie Gallardo, 39, can still harvest 5,000–7,000 megalopa from duyan-duyan nets. Despite pandemic-driven price drops—from ₱13 per piece to as low as ₱1–₱2, —he continues the work because hundreds of local families depend on it.

Gallardo leads the Cota na Daco Crablet Workers Association, which now supplies the coin-sized crablets—at ₱20 each depending on demand—to aquaculture operators in various provinces, from Quezon, Masbate, Bulacan, Pampanga, Zambales and Bataan in Luzon to as far as Iloilo and Leyte in the Visayas and Pagadian City in Mindanao. These young crabs are later farmed to market size for domestic consumption or export.

Gallardo has seven nurseries, each rented at P2,000 a month, in Barangay Cogon.

Their perseverance reflects a reality shared by many: the work is challenging, but the community has adapted before, and can continue adapting with the right support.

Community-led sustainability practices

Crab farmers are aware that the future of their livelihood depends on the health of mangroves and coastal waters. While they maximize artificial pens for early crab growth, they also emphasize that nothing can replace the role of nature.

When allowed to grow naturally in the wild, crabs face a higher risk of mortality because of various environmental factors.

“If we just leave them in the open sea, they might not even survive within a week because there are too many factors. There are predators, pollution and the change in water conditions,” Gallardo said.

Without this practice, more than 200 small-scale fishers in the coastal villages would lose their livelihood.

“The natural needs of crabs to live, to survive and to flourish still depend on nature,” said breeder Allan Espallardo. “That is why it is very important for us to protect the environment. It is the source of everything that sustains human life.”

Espallardo’s group regularly releases gravid (egg-bearing) mother crabs back into the wild to maintain the natural breeding cycle. One released crab can lead to a surge of megalopa in as little as two weeks—evidence of how human intervention and natural regeneration can complement each other.

“Based on our experience, when we release one mature crab, after two weeks we can already catch a lot of megalopa,” he said.

This practice illustrates a wider recognition: artificial ponds help farmers earn income, but long-term sustainability hinges on healthy mangroves, stable salinity gradients and intact coastal pathways.

A community coalition preserving both livelihood and habitat

Save Gubat Bay Movement, a community-based coalition of fishers, artists, environmental advocates and civil society groups in the town of Gubat helps to protect the natural life cycle of crabs. They restore mangroves, rehabilitate abandoned fishponds and engage residents in conservation.

Espallardo said SGBM helped them maintain the natural cycle to sustain the crab populations and preserve the livelihood of hundreds of small-scale fishers who depend on catching megalopa in Cota na Daco and nearby barangays.

Between 1998 and 2001, over 100 brackish-water ponds were established in Barangays Cogon, Cota na Daco and Tiris when the nursery culture for crablets began to boom.

The area, spanning at least 10 hectares, was converted from abandoned waste dumping site into productive nurseries. These transformations reveal how communities can reclaim damaged spaces and turn them into sources of livelihood and ecological recovery.

Government and community working toward long-term solutions

The Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) recognizes Sorsogon and Catanduanes as critical crab seed-stock areas due to their mangrove systems and coastal topography. But hatchery-based crab breeding remains a challenge nationwide. Farmers still rely on wild megalopa, making natural populations vulnerable.

To address this, BFAR plans to establish crab hatcheries in Catanduanes and, later, Sorsogon. These areas are identified based on natural mangrove stocks and topography, which provide ideal environments for crab reproduction.

“Hatcheries can reduce pressure on wild stocks and stabilize supply,” said Nilo Consuelo, chief of BFAR’s fisheries production and support services division in Sorsogon. “We want communities to benefit without harming the ecosystems that support them.”

They still rely entirely on wild sources for hatchery stock as controlled breeding in hatcheries has not yet been fully established.

Consuelo said crablet cultivation programs have been proposed and will be funded in Catanduanes in 2026, while similar initiatives were also planned for Sorsogon, to support sustainable production.

However, hatchery development requires support from local government units for funding and long-term planning—another layer in the evolving system of coastal resource management.

Consuelo also highlights stricter rules: new brackish-water pond development is no longer allowed to prevent further mangrove loss. Only abandoned or inactive ponds can be used, balancing livelihood needs with environmental protection.

Climate impacts and evolving threats

Coastal communities here are feeling the effects of climate change. Rising temperatures, shifting seasons and increased storms affect crab behavior and breeding cycles. Mangroves—critical nurseries—are sensitive to these changes.

Crabs also rely on unobstructed migratory routes. Poorly designed seawalls or coastal roads can block movement between the sea and mangroves. “Obstructed pathways can disrupt entire life cycles,” Consuelo said.

In 2022, SGBM and local residents successfully halted the construction of seawalls and reclamation projects in key crab nursery areas such as in Barangays Cogon and Cota na Daco, protecting vital crab nurseries. Yet similar structures in neighboring villages continue to alter water flow and sediment patterns.

Similar projects have been constructed in Barangays Bagacay, Buenavista, Panganiban, Pinontingan and Balud Del Norte and Del Sur.

The series of storms during the “ber” months that struck the Bicol Region brought floods that carried heavy mud deposits, turning the brackish waters and coastal shores brown. Quarrying in upstream areas adds to sediment flow, threatening both mangroves and the crabs that depend on them.

These changes highlight the need for integrated coastal management, particularly collaboration among the fisherfolk, LGUs, BFAR and environmental groups.

Seeing the future through community resilience

Despite challenges, crab farmers in Sorsogon continue to innovate. By combining traditional knowledge with emerging practices—like releasing mother crabs, using abandoned ponds, participating in cooperatives and supporting hatchery initiatives—they are building a more stable future for a coastal livelihood shaped by both nature and industry.

For many in Gubat, sustaining crab farming is not only about income. The goal is not merely to save a livelihood; it is to keep coastal ecosystems thriving so the next generation can inherit both the crabs and the coastline that have shaped their way of life.

As coastal conditions change, the community’s continued involvement in decision-making, resource protection and policy development will be central in ensuring that this “backyard hope” remains a source of life for generations.

* Ma. April Mier-Manjares, correspondent for the Philippine Daily Inquirer- Southern Luzon, is a VERA Files fellow under the project Climate Reporting: Turning Adversities into Constructive Opportunities.

This story was produced with the support of International Media Support and the Digital Democracy Initiative, a project funded by the European Union, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, and the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation.

The views and opinions expressed in this piece are the sole responsibility of the writer and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation, and International Media Support.