Update: Feb. 22, 2026

Justice Carpio sent us these infographics in response to this article:

___

In styling himself an international law expert, retired Justice Antonio Carpio has only managed to tie himself up in contradictions. His recent attempt to defend his ponencia in Magallona v Ermita (2011) only tightens the knot he now struggles to untangle. The landmark case had sought to declare Republic Act No. 9522 (2009) or the Archipelagic Baselines Law unconstitutional.

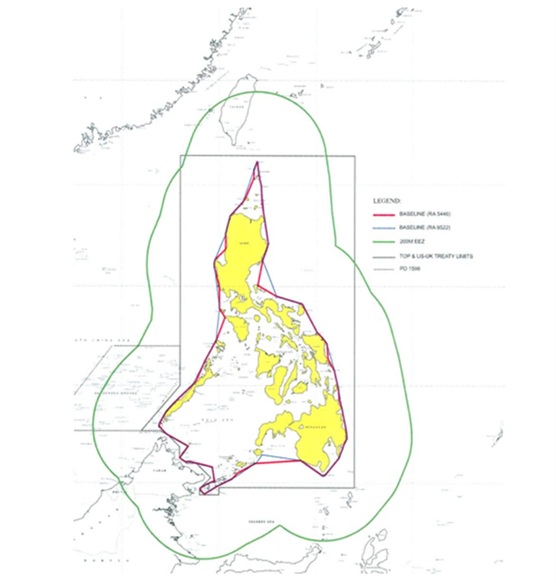

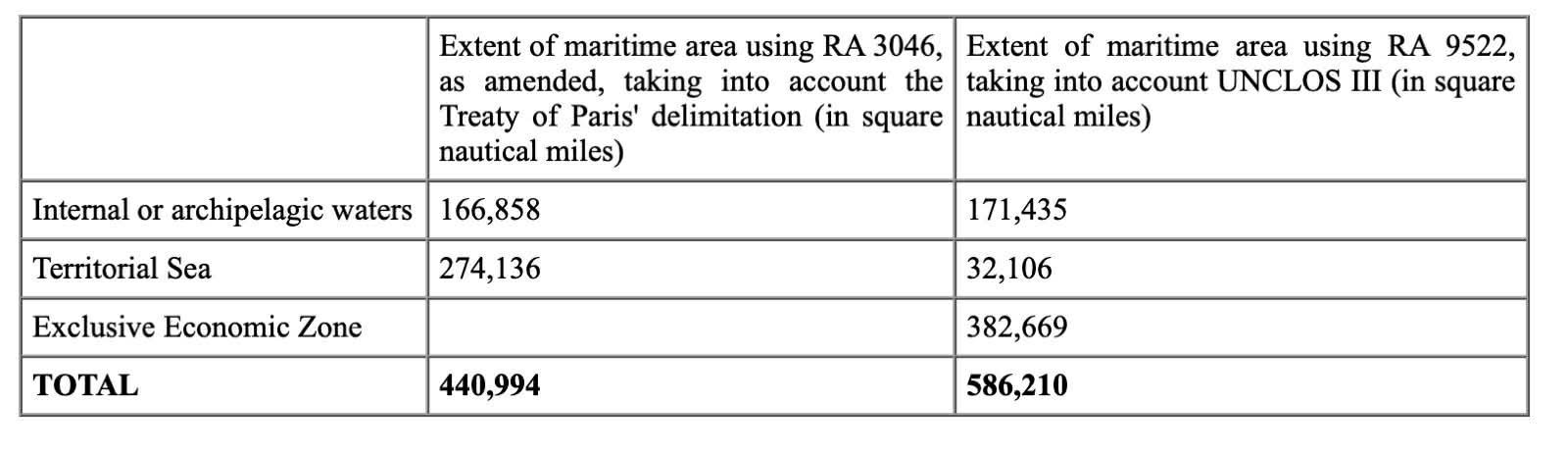

His ponencia presented a table comparing the extent of territorial sea (TS) and exclusive economic zone (EEZ) under the old baselines law (RA 3046, 1961) and the new baselines law (RA 9522, 2009). In that table he acknowledged that the TS under RA 3046 stretched up to the limit set by the 1898 Treaty of Paris and therefore spanned 274, 36 square nautical miles (SNM). Under RA 9522 and UNCLOS, the TS will stretch only up to 12 NM and therefore contract to 32,106 SNM. He wrote:

The table clearly acknowledges a territorial loss. Hence, the accusation that with his ponencia, Carpio had surrendered 242,030 SNM of Philippine territory without a fight.

Carpio deflected the blame to the late Professor Merlin M. Magallona, in his time the Father of Philippine international legal scholarship. Magallona passed on in 2022 and is now unable to defend himself from the slur to his knowledge and expertise.

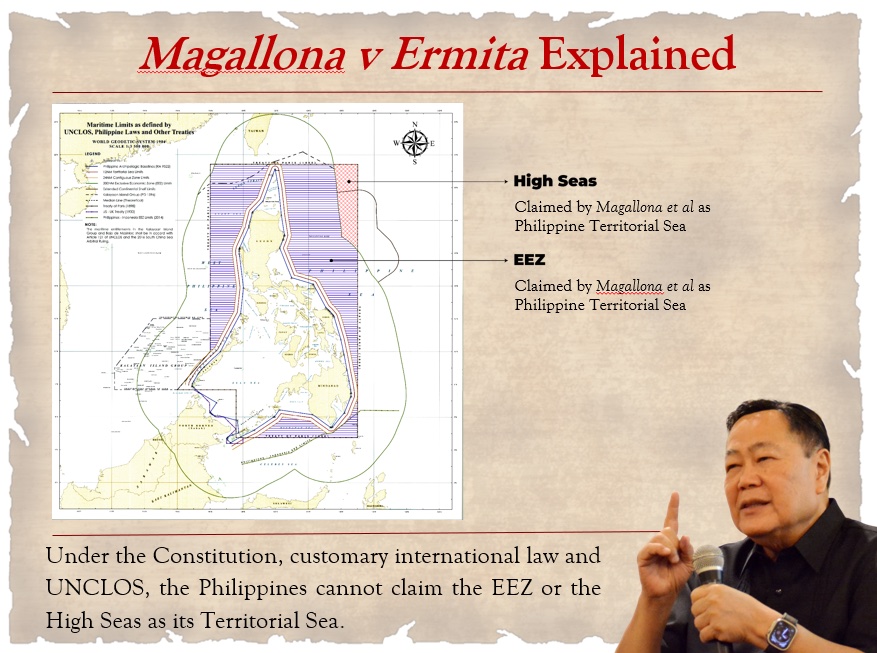

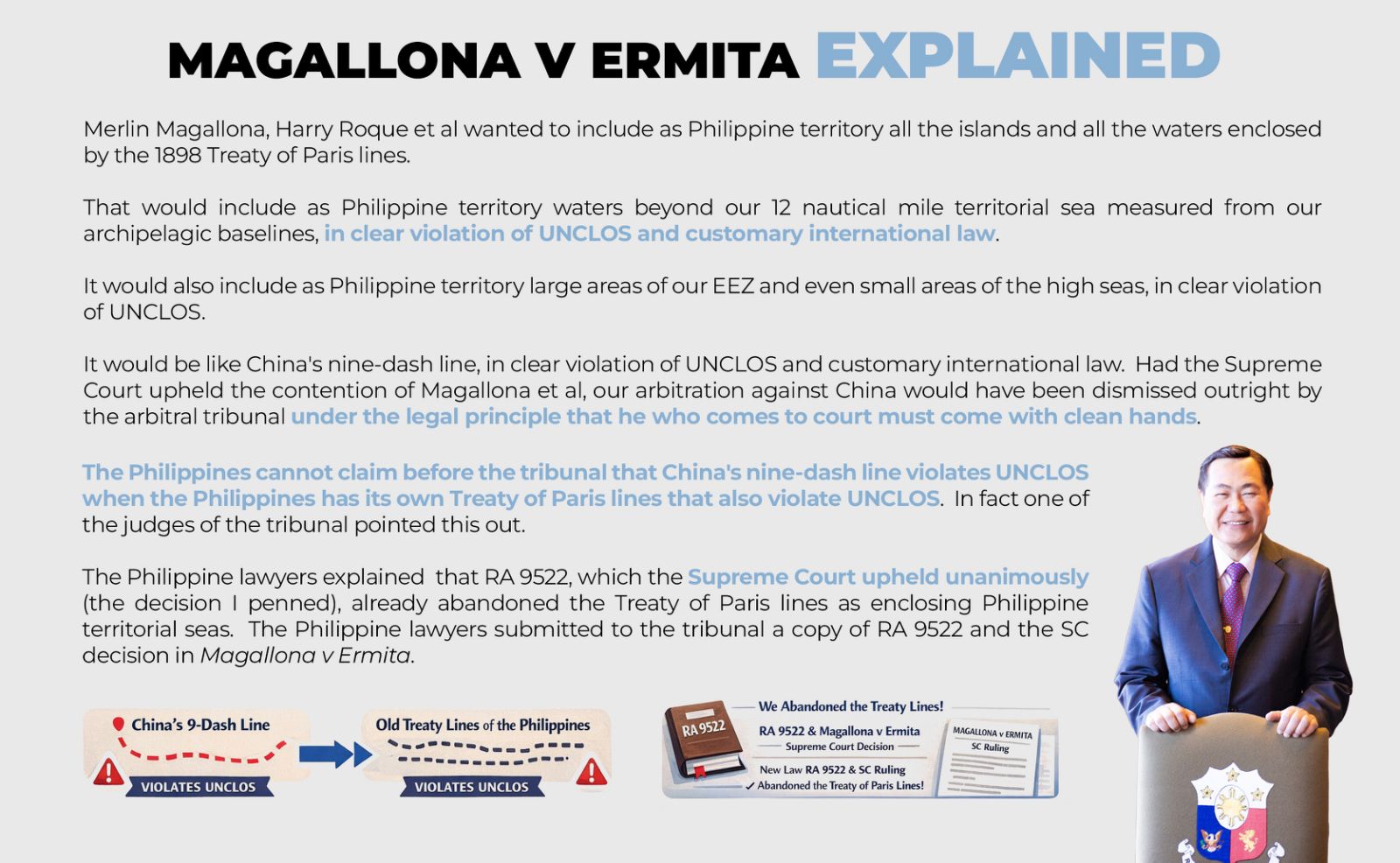

Carpio claimed in public statements that Magallona had “wanted to include as Philippine territory all the islands and all the waters enclosed by the Treaty of Paris (TOP) lines,” referring to Article 3 of the 1898 Treaty of Paris whereby Spain ceded the Philippines to the United States.

Yet Carpio’s comparative table clearly recognized that before RA 9522, the existing Philippine TS covered 274,136 SNM, and that after his ponencia, that same area shrunk to no more 32,106 SNM. Indeed, under RA 3046, our TS was double the combined land area of the Philippine archipelago of approximately 116,000 square miles. Under the 1935 Constitution, the Philippine national territory embraces “all the territory ceded to the United States by the [TOP]… the limit of which are set forth in Article III of said treaty”(Section 1, Article 1).

In 1961, RA 3046 interpreted this to mean that “all the waters beyond the outermost islands of the archipelago but within the limits of the boundaries set forth in the aforementioned treaties comprise the territorial sea” and that said territorial sea is “part of the territory of the Philippine Islands.” RA 3046 drew from Article 1 of the 1898 TOP and Article 1 of the 1958 Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone Convention. Even the United States as party to the Treaty of Paris and the colonial government of the Philippines declared before the Arbitrator Max Huber in Island of Palmas case (1928) that these waters adjacent to the Philippine archipelago and up to the treaty limits are part of the Philippine territory.

This definition of the Philippine national territory, including the 274,136 SNM TS, was maintained by the 1973 and 1987 charters Thus, our TS of 274,136 SNM has long been constitutionalized. Magallona had simply sought to preserve this vast territorial sea and the sanctity of the definition of the national territory in the Constitution.

RA 9522’s lead author, Senator Miriam Defensor Santiago, had anticipated a potential conflict between Unclos and the Charter. She wisely inserted a no-prejudice clause “affirming that the Republic of the Philippines has dominion, sovereignty and jurisdiction over all portions of the national territory as defined in the Constitution and by provisions of applicable laws….” (Section 3).

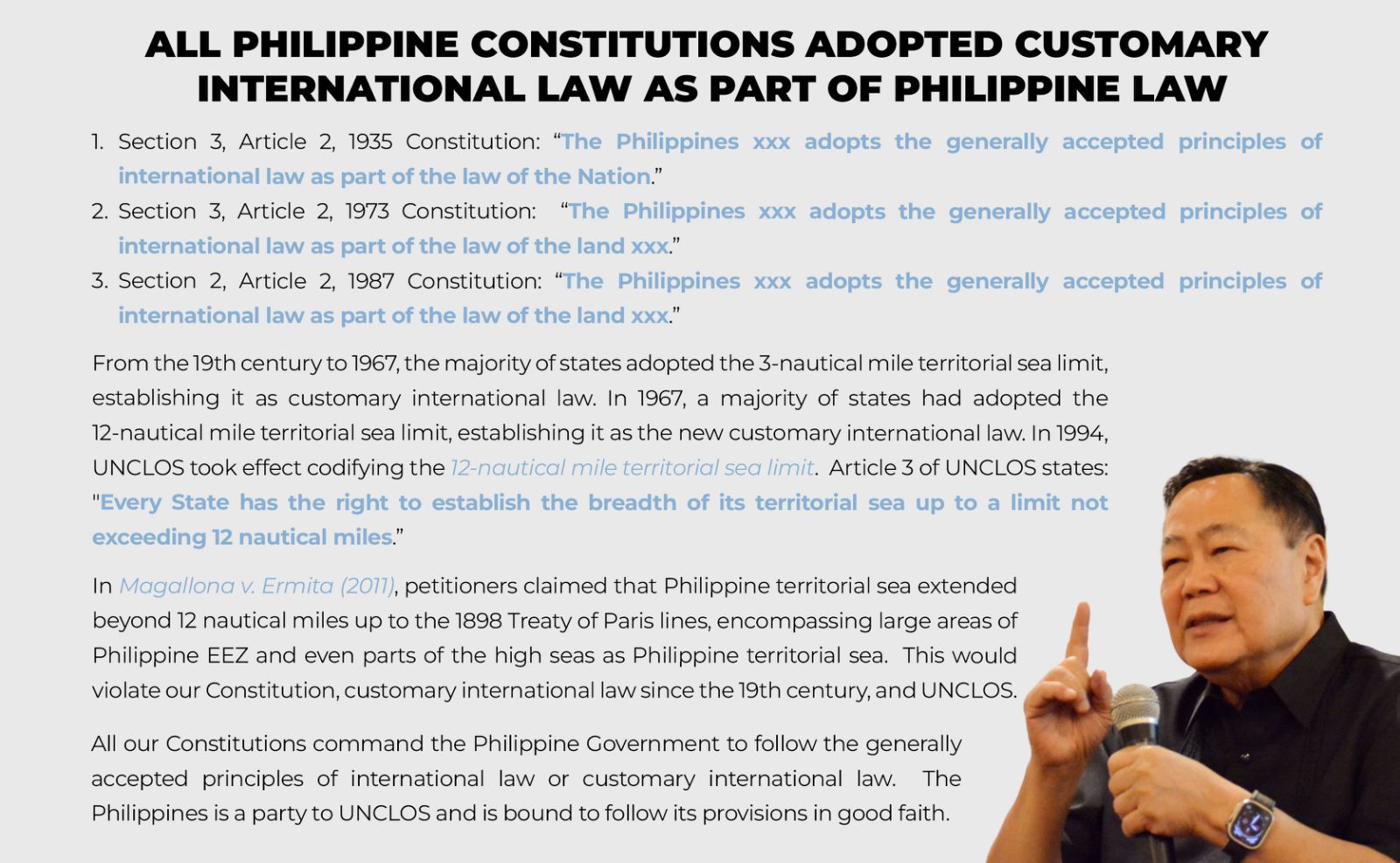

Thus, there is no proviso in RA 9522 changing the limit of the TS to the Unclos-prescribed 12 NM. Moreover, in her sponsorship speech, Santiago had urged the executive department to study the potential conflict between the law of the sea and the Constitution. She ensured that RA 9522 would not amend the Constitution. After all, while the Constitution declares that international law is part of the law of the land, it does not elevate international law to the same level as the constitution much less allow international law to amend any provision of the constitution. No provision of UNCLOS or any law implementing it or any decision interpreting can amend Article 1 of the Constitution.

Carpio ignored these red flags. By judicial fiat, he grafted Article 3 of the Unclos into RA 9522, imposing a 12-NM limit on our TS. By one stroke of his pen, the national territory provision of the 1987 Constitution was amended without the requisite constitutional procedure.

Carpio shrugged off our substantial territorial loss by saying it is more than compensated by a gain of 382,669 SNM of EEZ. This betrays a lack of knowledge of a basic principle of international law that the TS always trumps the EEZ (Nicaragua v Colombia, 2012; Nicaragua v Honduras,2007).The TS is part of a state’s territory; the EEZ is not. In its TS, the Philippines enjoys full sovereignty, including dominion over all oil and gas resources in situ, even before they are discovered and extracted. In the EEZ, the Philippines enjoys limited economic rights, such as vested ownership of the oil and gas only after discovery and extraction.

Carpio’s Faustian bargain may have enabled us to prevail over China’s nine-dash line (2016 Arbitral Award, paragraphs 223,225-228,261). But we wonder, given Carpio’s actuations of late: Why did China’s nine-dash line map surface in 2009 just some two months after RA 9522 became law? Was the judicial sacrifice of territory worth an EEZ, especially as, until now, pockets of it are disputed?

Carpio is now pushing a revisionist Philippine claim over the Spratlys islands. He argues – irony of ironies – that the TOP limits, as extended by the 1900 US-Spain and 1930 US-UK treaties, embraced the islands. He fails to realize that in dissolving the TOP limits and downgrading the territorial status of the enclosed waters, his ponencia not only altered the constitutional definition of our national territory but also placed the Spratlys beyond its reach. Having denied that the waters adjacent to the Philippines and up to the limit of the treaty limits are part of the Philippine territory, how can he now leapfrog and claim areas outside that limit, i.e. Spratly Islands, as part of the Philippine territory?

The Supreme Court settled Magallona versus Ermita. History will judge Carpio versus Carpio.

Loja and Bagulaya each hold a PhD Public International Law from the University of Hong Kong. Bagares is a doctoral researcher in international legal theory at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.