Text and Video By COOPER RESABAL

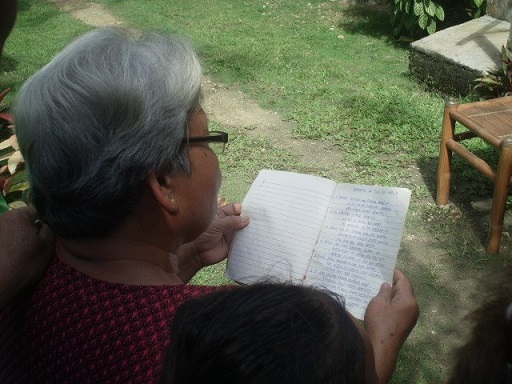

MARIBOJOC, Bohol – Simeona Guilen, in her sixties, opens the pages of a discolored notebook containing the handwritten lyrics of “Daygon sa Igue-Igue/Pagkatawo” (Praise for the Birth), a fast disappearing folk Christmas musical tradition in the island province featuring dancing “pastores” (shepherds) and the Holy Couple being refused a place in several homes before finding a stable where the Holy Child is born.

Accompanied by a blind banjo player, two guitarists and a bass guitarist, a team of “igue-igue” singers tries to sing the opening salutation of the folk tradition mostly by memory.

“We need to put notes on the oral rendition of the songs to document the heritage tradition,” says Enriquieta Butalid, former head of the Center for Culture and Arts Development (CCAD) office in the province. “That way, it can be conserved for posterity,” she adds.

Fructuosa Hibaya, 80, who inherited the “Igue-Igue” songs from her mother Petra, a cantor, lamented that if no step is taken to fully document the Christmas musical tradition, it could disappear with the old folks.

The last full version of the “Daygon sa Pagkatawo” (Carols of the Birth) in recent memory was presented by the Baryo Amigo Cultural Troupe (BACT) of Toril, Maribojoc, on December 17, 2011 at the Rizal Plaza in Tagbilaran as part of the Bohol Arts Festival that year.

Dubbed “Mga Eksena sa Igue-Igue Daygon sa Pagkatawo,” the folk version of the various incidents before and after the birth of Jesus Christ was based on a selection of the oral tradition as practiced every December in the 1950s up to the 1970s in Toril, Maribojoc town, and other parts of the island, say sources from the Bol-anon Village Cultural Trails.

“Igue-igue sa Pagkatawo” is also popularly known as “pastores” due most likely to the dancing pastores that is featured in many scenes. It is set in the ancient Roman Empire.

Calixto Recamara, 64, whose clan has the privilege of being handed down the “Igue-Igue” oral tradition in barangay Toril, Maribojoc, said there were three parts of the music tradition. Carolers sang “Daygon sa Igue-Igue” before December 25, then the “Daygon sa Pagkatawo” on December 25, and the third part “Daygon sa Tulo ka Hari” at the end of December, up to the feast of the Three Kings, which closes the Christmas season.

In the course of the research for the 2011 presentation, it was found out that the popular carol, “Ania Kami, ning Gabii sa Among Pagdaygon…” came from the original “Igue-igue.” The rondalla traditionally accompanies the “igue-igue” carolers.

Melyn Borcelas, who was part of the Research Committee on the folk musical tradition in Maribojoc and Antequera, played the part of Virgin Mary, but Fructuosa Hibaya and Semi Gillen sang her dialogue. Ursesio Amon played the role of St. Joseph, while Calixto Recamara sang his dialogue. Some village folks of Toril, Maribojoc, played other parts, like the three kings, house owners, Roman soldiers and “pastores.”

The hour long Christmas musical was an instructional tool for people to know the story of the nativity, including some of the doctrines of the Church hierarchy regarding the nature of the birth of Christ. The lyrics say, “Gipanamkon nga ulay nga Vergin, gianak didto sa Belen. Putling kahimtang salamin, ang pagkaulay dili mabalhin.”(Conceived without sin, born in a stable, mirroring an immaculate unchanged condition).

It describes how Christ was born, which all those commercialized Christmas celebrations contradict, “Nag-antus sa mga kapobre, gipahigda sa presepre. Ang banig habol gisilbi ang uhot, ug ang dagami.”(In poverty, he was made to lie in a box, with hay as bed and blanket).

The “pastores” carol brings the key message of salvation: “Ang pulong sa anghel sabton ta, kay ang dakong kalipay midangat na, kay natawo tungod kanimo ang manluluwas nga Ginoo.”(Listen to the angels’ message that brings great joy since the Savior is born).

Marianito Luspo, former head of the Bohol Arts and Culture Heritage Council (BACH), recalled in a Facebook post that “the Bisayan Christmas used to involve putting up elaborate Belens or crèche in the living rooms of the faithful. In the grand houses, this almost always meant appropriating half of the sala for this artistic representation of the first Christmas. The reason for this was not so much aesthetics. I remember my mother used to explain to us that this was to make it easier for the “manaygonay”- the people who come to sing the Dayegon- to make their obeisance to the newborn Jesus.”

“Dayegon,” he said, means “to praise. It might well mean to give honor, adulation and worship to someone of great stature. In earlier times, the manaygonays would go up houses and the first thing they ask was, “Where is your Belen?” he said.

Luspo further recalled how simple folks from the barrios, unwitting carriers of our old traditions, would reverently kneel before the crèche before launching into a spirited repertoire of praise and worship in song and dance. One traditional dayegon from Loboc town is illustrative of the praising nature of this musical tradition:

Juana* ang akong ngalan,

ubos intawon nga pastores;

Aniay bulak akong dala

ihatag kang Maria! La-la-la-la-la-la.

(Juana is my name, a lowly shepherd. I’m bringing flowers I’m offering to Mary. La la la la).

Professor Luspo of Holy Name University observed that dayegon used to start with acknowledgment and greeting to the homeowners. This is then followed by the adoration song and dance, performed with the singers intently looking at the Baby Jesus. Then it culminates with a farewell routine in which the manaygonays bade farewell to the Holy Family and the “Tagbalay nga Bulahan” (Household Owners).” Interestingly, this is the same sequence followed by the Balitaw, the ancient art of love joust set to music and which is one beloved art form among Bisayans,” he noted.

The cultural researcher said that “while these songs were taught amidst the dominant backdrop of Western colonization, there was no wholesale importation of tradition here. Coming from the native peasantry, the dayegons reflect an insistence at localizing or contextualizing the faith they received from a foreign source.”

“This makes the dayegon a valid expression of Filipino culture,” he adds.

In terms of musical treatment, he observed that “the dayegons were originally set to the pastorella time signature, i.e ¾ with emphasis on the downward beat. Again this is indicative of European origin. The dayegons that came out during the late 1920’s are recognizable because of their heavily syncopated beats. The history of 20th century music bears this out.”

He contended that “the Jazz Age brought about not just a new liveliness to the traditional dayegons, it also marked the commercialization of the genre and led to its present-day degeneration.”

Luspo clarified that “the original dayegon was…intended as a devotional practice, allowing ordinary folks to concretize their joy over an important article of the Catholic faith. The going from house to house was aimed primarily at making repeated adorations to the Christ Child, a form of prayer. This means it was never done with the intention of soliciting goods from householders. If the homeowner, grateful for the visit, offered refreshments or token money, it was not the manaygonay’s intention.”

In the evolution of the new form of dayegon, “it was not anymore imperative for the manaygonays to perform before the Belen. In fact, the object of the performance was now to please the Tagbalay nga Bulahan (the Lucky Homeowner) – as a source of favors. The dayegon has slowly become an outside-the-window performance, a yuletide serenade.”

In Luspo’s view, “this caused the eventual diminution of the traditional Belens of Bohol. While before there was a need to appropriate one half of the sala to cater to walk-in devotees, the new Belens became simpler table installations set in one corner of a vast living room.”

For inquiries regarding the Bol-anon Village’s “Daygon sa Pagkatawo,” call or text 09216567928. Or visit this website: www.bol-anonvillageculturaltrails.com