Images by R.C. Ladrido

Sacred Shores is Dengcoy Miel’s current exhibit until July 31, 2024 at Kaida Contemporary, Quezon City.

Or is it Scared Shores? In this latest exhibition Miel reflects on the idea of ownership, sovereignty, and territory amidst Filipinos’ seeming apathy to the issue.

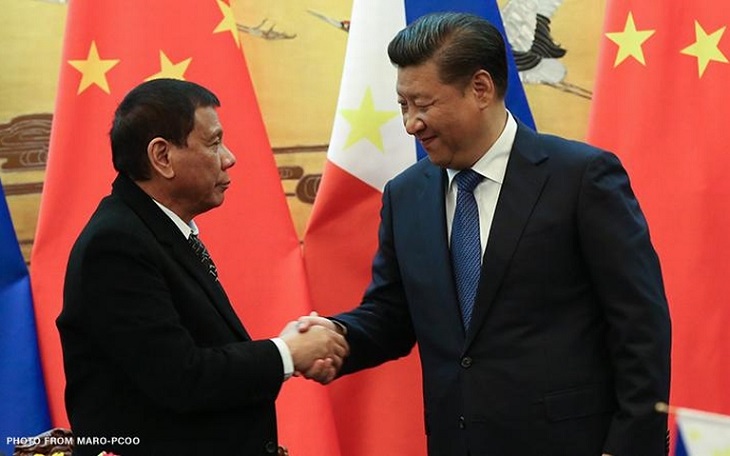

Eight years after the international arbitral ruling on South China Sea (2016) in favor of the Philippines, China has blatantly ignored the ruling and continues its harassment and provocation against the Philippines.

Amidst China’s actions, the Philippines could only talk of rights and sovereignty. As everyone knows, the country has no real defense capability against China on its own; its mutual defense treaty with the United States remains to be tested.

Dengcoy Miel presents seven acrylic paintings, all done in 2024. Laced with irreverence and overlaid with surrealistic images of pop culture, art history, mythology, and current events— Miel’s works portray the issues of the day that prick our sense of right and wrong. And yet, we remain bystanders.

Third World Narcissus: In Greek mythology, Narcissus was known for his beauty. A blind seer warned him that it was unlucky or fatal to gaze at his own reflection, in vain.

It depicts a giant of a beautiful man almost stretched on a bank of a putrid river, gazing at his own murky reflection, and surrounded by makeshift shanties that remain in danger of being reclaimed by water. Finely detailed images of its dwellers who go about their ordinary and tedious lives: washing dishes and clothes, having sex, praying, watching by the window, throwing leftover food, or even defecating.

West Philippine Sea: In three parts of blue, red, and yellow colors of the Philippine flag that serves as a background of a country in distress in dealing with the issue of maritime sovereignty and China.

Amidst an expansive blue sky, a cartoonish dragon looks on, as a ship named Pilipinas sinks slowly. A large red sea of fire, full of debris and Filipinos trying to stay afloat, gasping, clutching at their material belongings, or holding to a wooden cross (no, prayers will not cut it). Others cling to a lifebuoy face of Rizal, the saviour who laid down a path for us to follow.

On top of a yellow wall, the status quo of the powerful and their hangers-on laugh and sneer at the suffering people below; one even urinates with glee on them. With a bouffant hairdo, a plump Imelda bedecked with pearls, looks on.

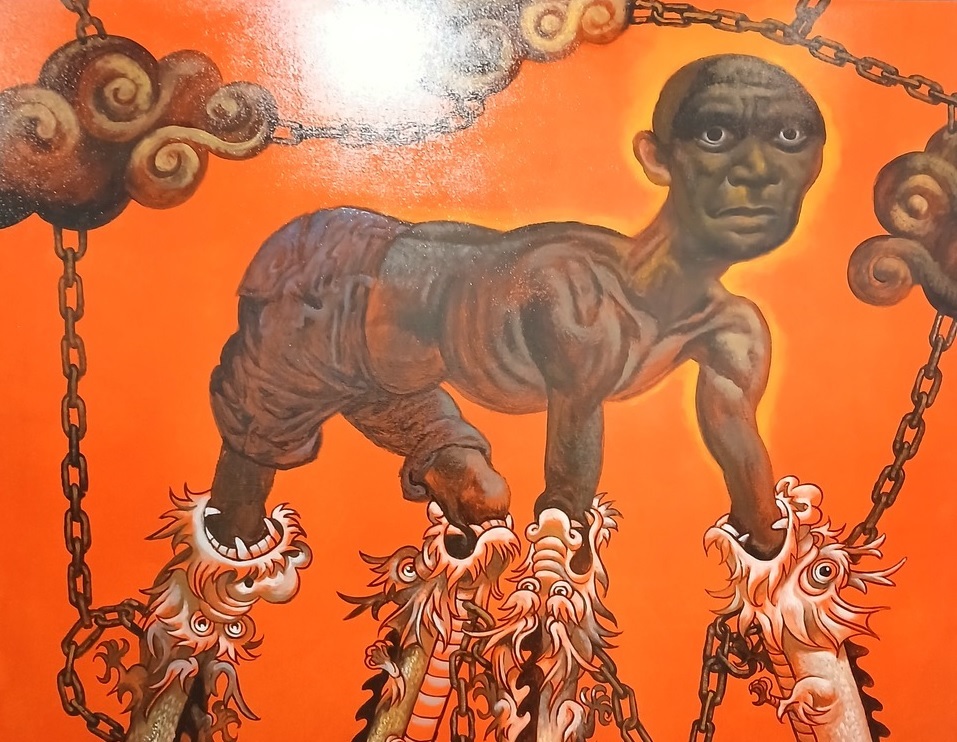

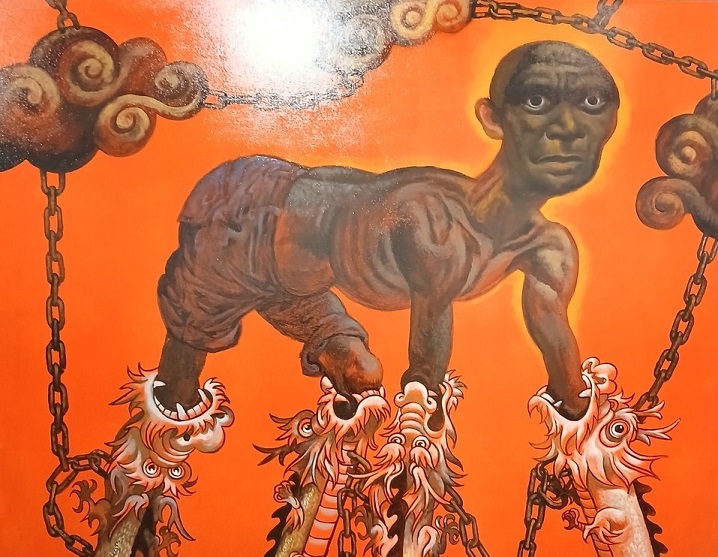

Nine Dash Line: A map of territorial claims traced by heavy metal chains, and within its boundary, a brown man with his arms and legs shackled, trying to move on stilts shaped like dragons. Their razor teeth bite and hold him down.

Mapait na Asing Dagat: Alone, a fisherman on his wooden boat with a broken oar and an unfastened anchor faces the sea with dark stormy clouds and sparks of lightnings. What dangers await him? Will he get a good catch today to support his family?

Z is for Zal (Vigilante): Wearing a Zorro mask, Jose Rizal looks in pain and despair. The national hero’s historical legacy is a recurring image in Miel’s work, a reminder that Rizal’s ultimate sacrifice for the nation remains unfulfilled, unfinished.

Clarity is within our grasp. A firm and resolute response, beyond greed and political posturing, may save the day.

The antihero in us

How do you love a country like the Philippines?

For the ordinary Juan, feeling patriotic may just be a fleeting emotion; the West Philippine Sea has never been a pressing issue. Rising prices of basic goods, hunger, poverty, and job security remain top priorities for Juan de la Cruz.

Dengcoy Miel (b. 1964)

A Filipino cartoonist, illustrator, and a senior executive artist at The Straits Times, Singapore’s top English language newspaper.

With a fine arts degree from the University of the Philippines Diliman and a master’s degree in design from University of South Wales, Sydney, he was an editorial cartoonist for the now defunct Philippine Daily Express, owned by former president Ferdinand E. Marcos. He was the chief editorial cartoonist of Philippine Star, a paper founded in the post-Marcos year in 1986. In 1992, he and his family relocated to Singapore where he started as the assistant arts editor of The Straits Times.

He has received the National Cartoonists Society’s award for newspaper illustration twice, in 2001 and 2013 and two awards in Excellence in Editorial Cartooning from the Society of Publishers in Asia (SOPA) in 2007 and 2011.

His work is published in newspapers such as Courrier International, The International Herald Tribune, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and Newsweek, among others. It is included also in some international cartoon books such as The Finest International Political Cartoons of Our Time (1992) and The Best Political Cartoons of the Year series by Daryl Cagle.