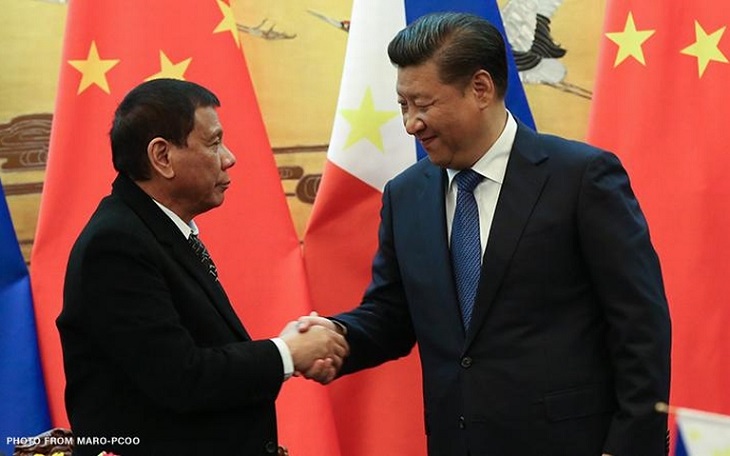

China’s President Xi Jinping welcomes Pres. Duterte to China in October 2016. Malacanang photo.

May President Rodrigo Roa Duterte enter into a valid verbal executive agreement with China to allow Chinese fishing vessels into the Philippine Exclusive Economic Zone?

Senator Francis Tolentino, who has a master’s degree in international law from a top London law school and attended the prestigious Hague Academy of International Law, believes so.

That, at least,is what reports emanating from the august halls of the Senate Monday said of his inaugural appearance as a member of the Upper House.

Sparring no less with a veteran senator and no mean lawyer himself –Franklin Drilon – after his privilege speech,Senator Tolentino defended the reported verbal agreement made by President Duterte with Premier XI Jinping as the President’s exercise of his powers as the” Chief Architect of Philippine Foreign Policy.”

One thinks his political allegiances made Senator Tolentino forget his public international law, which was his major as a graduate student at the University of London. Or perhaps, he simply forgot.

An executive agreement is really a term in domestic law that applies to a treaty under international law.

The Oxford Public International Law online dictionary defines it as “treaty that has been concluded and ratified by the executive branch without formal approval by a legislative body, in a State in which treaties are usually ratified only with such approval….” It adds that‘the term executive agreement refers only to the status of the agreement within the domestic law of the State in question…. For international purposes, the instrument is simply a treaty or international agreement…”

And an essential element of a treaty is that it must be in some written form, entered into by states, and governed by international law, as provided inArticle 2 (1) of the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. It’s a practice as ancient as early civilizations, really.

The Assyrian King Esarhaddon (680-669 BCE), meticulously kept a record of treaties he entered with other kings (in his case, engraved in clay tablets). The Muslim Sultanates of Mindanao, at the height of their power, knew treaty-making very well, as shown in their tarsilas.One would think, following ancient practice, and our own forbears, we’d be wiser now, even without having to read Sun Tzu’s Art of War.

In many leading cases, our own Supreme Court has recognized that there is no essential distinction on the status of executive agreements and treaties, at least, as to form. First of all, they must be written, in whatever form – even on office stationery (which is where ambassadors write notes, right?)

Moreover, there is a Ramos Executive Order– Executive Order 459, series of 1997 – that has become some sort of a bible for how our Department of Foreign Affairs carries out its mandate when negotiating treaties with other states on behalf of the President. Section 2 of EO 459 reflects the language of the Vienna Convention when it defines executive agreements as “similar to treaties, except that they do not require legislative concurrence.” I would quibble with some of the phraseology in this Executive Order, but I’d hold that this definition given suffices, for our present purposes.

Elsewhere, I have written that executive agreements in Philippine law are quite interesting animals, primarily because they are usually based on an earlier treaty that is purportedly being implemented by such executive agreements.

They thus exhibitwhat legal theorists would call a “quasi-monist” character (because they don’t anymore require legislative – or even judicial –action). However, the paradox is that they only come to being because of thatquintessentially“dualist” device of the treaty, which must first be approved by the Senate under the Treaty Clause of the Constitution (See myPhilippine Chapter in the Oxford Handbook of International Law in Asia and the Pacific, OUP, Chesterman, Owada and Saul, eds., forthcoming, August 2019). Thus, the Supreme Court would often tact the validity of an executive agreement to an originating treaty.

Which leads me to the question –assuming there was such a discussion between President Duterte and Premier XI Jinping, what was its originating treaty? It may be plausibly argued that it was based on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) itself, since both the Philippines and China are parties to the multi-lateral treaty.

But then, if that’s the case, things get more interesting.

UNCLOS has a particular understanding of exclusivity as an incident of a state’s sovereign rights over the EEZ. Under the Law of the Sea, it doesn’t mean full, or total exclusion of other states from the EEZ of a coastal state. In simple terms, it does mean, in the case of the Philippines, its Total Allowable Catch, which is a scientificmeasure of a coastal state’s total harvesting capacity, with due regard to issues of conservation and sustainability (Article 61 [2}, UNCLOS).

Which also means that,in excess of the TAC, the Philippines has an obligation under the Law of the Sea to allow other states to fish in its EEZ for the “surplus catch”, and no more, no less. . Ironically, even China questioned the UNCLOS’ allotment of a surplus catch in a coastal states’ EEZ for other states, as noted in great detail by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in its judgment in the Philippines-China Arbitral Case.

In the UNCLOS negotiations, the capacity to scientifically establish their TAC was a major concern raised by developing states. I’d like to believe the Philippinesnow has the scientific wherewithal to determine its TAC.

But the idea of the TAC goes against Article 12 (2) of the 1987 Constitution, which states in no uncertain terms that “The State shall protect the nation’s marine wealth in its archipelagic waters, territorial sea, and exclusive economic zone, and reserve its use and enjoyment exclusively to Filipino citizens.”

President Duterte’s distressing remarks about an executive agreement that seemed to have been written on water has prodded Justice Antonio Carpio to go as far as practically going against his own ponencia in the case of Magallona v. Executive Secretary (G.R No. 187167, August 16, 2011). Justice Carpio, a vocal critic of the government’s stance on China after our own Arbitral victory, has gone on record to say the Constitution is superior to the UNCLOS on the question of the Philippine EEZ.

In Magallona, in which we challenged the constitutionality of the new Baselines Law, Republic Act 9522, Justice Carpio had said there is no conflict between the Law of the Sea provisions on maritime entitlements and the National Territory provisions of the 1987 Constitution.

Otherwise, Justice Carpio is right to warn that if the President keeps on talking about a verbal agreement through which he supposedly granted the Chinese fishing rights in our EEZ,we will be bound by it via the doctrine of a binding unilateral declaration, in the most disadvantageous way possible. Without clear provisions on conservation and management of resources, such a declaration would give China – with 1.5 billion mouths to feed – a free hand in depleting our already strained maritime resources in our EEZ. But that would not be an executive agreement, but a sorry way of bargaining away our national patrimony for absolutely nothing,

Going back tothe verbal executive agreement beloved of Senator Tolentino: how to cure it?As they say, yamang nandiyan na tayo.

Well, that may be remedied by an exchange of notes between the ambassadors of the two countries (as a follow up to the verbal discussions between the Heads of State of the two countries).

The President has the opportunity here to actually assert Philippine jurisdiction over its EEZ lying in the path of the debunked Chinese Nine Dash-Line claim. Under certain conditions, he would be correct to say that we do have a legal hold over the EEZ, if we are able to formally and legally allow the fishing vessels of another state to fish in it.

Of course, the devil will always be in the details of such an agreement. At the very least,a properly executed executive agreement, if it actually comes to pass, should provide for conservation and sustainable fishing practices, as well as protection for our fishermen from harassment by China’s “Surging Second Sea Force” –its vaunted naval militia working in concert with its giant fleet of civilian fishing vessels.

Section 1 of Executive Order 459 provides that any negotiations for such treaties or agreements must be made only with the participation ofthe Department of Foreign Affairs, with the appointment of the head of the Philippine negotiation panel made in coordination with the Department.

It’s time for our foreign affairs professionals to have their say on this matter of the national interest.

This is a revised version of the same article.The author, an alumnus of the University of the Philippines College of Law and the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, teaches public international law at the Lyceum Philippines University. Opinions expressed in this essay are his alone.