True to a Biblical reference on the wise man who built his house on a rock, BRP Sierra Madre stands defiantly on Ayungin Shoal in the West Philippine Sea (WPS) even as one of Asia Pacific’s top military superpowers has been trying to have it removed for almost 30 years now.

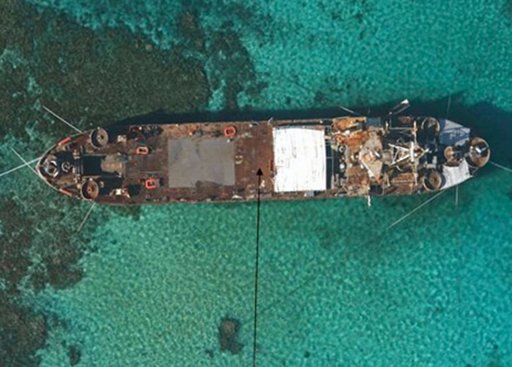

The rusting hulk was intentionally grounded by the Philippine Navy on Ayungin in 1999, after China occupied and built structures on Mischief Reef in 1995, 40 kilometers west of the shoal and well within the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

Almost 80 years old, the hardy BRP Sierra Madre had served numerous battles under other names. Built by the United States Navy in 1944 as a class tank landing ship, she was initially named USS Harnett County and saw action during World War II and the Vietnam War. She was transferred to Vietnam which named her RVNS My Tho before being turned over to the Philippines in 1976.

I set foot on BRP Sierra Madre on August 28, 2011. Clad in a life vest far out at sea in the early morning of that day, I climbed down what the Navy people referred to as “Jacob’s ladder,” an improvised step rope hanging on one side of BRP Laguna (LT-501). I then transferred to a rubber boat of the Navy Special Operations Group’s (NAVSOG) bound for Ayungin shoal.

First visit of journalists to Ayungin shoal

I was part of a group of reporters in what has become the first recorded landing of journalists on the contested shoal, but this was not my first trip to the Kalayaan Island Group (KIG).

As a reporter for the Japanese television network NHK, I had covered the routine troop rotation and resupply mission to the area. In a logistics run in 2005 to Philippine-held islands in the KIG that excluded Ayungin, we landed and got stranded on Lawak Island (Nanshan) because of a storm. It was in 2011, however, that media access to Ayungin Shoal was granted to NHK and the local network TV5.

Long before the Philippine Coast Guard (PCG) was met by the water cannons of the Chinese Coast Guard there, the Navy’s elite unit trained for special operations in unconventional warfare as well as sea, air, and land had routinely serviced the troops stationed at the BRP Sierra Madre.

Compared to the PCG’s over 40-meter multi-role response vessels, NAVSOG used its 11-meter rigid-hulled inflatable rubber boats powered by outboard motors to primarily insert reassigned troops and in this case, also deliver provisions to BRP Sierra Madre.

The Navy’s bigger ship BRP Laguna could only take us so far so we had to get on board three of those rubber boats. They were fast and got us there in 45 minutes, from the high seas to the shallow waters that submerged Ayungin, which is within the country’s EEZ.

BRP Sierra Madre’s staircase was made of narrow planks hooked and wired to corroded poles that creaked at every step as we climbed up. As the salty sea air breezed through, reeks of dried fish and old rusting metal permeated the air.

What contrasted with the sorry state of the ship, however, were the warm and happy smiles of the Navy personnel stationed there who welcomed us. They were excited to return home and see their families after their six-month tour of duty, but they gladly showed us around the BRP Sierra Madre.

The ship tour showed the decomposing state of the stationary outpost that I had expected. The magnitude of the decay, however was beyond what I had imagined. With its hull pockmarked with gaping holes and interior walls rusting away, the BRP Sierra Madre offered a visually-compelling illustration of how Manila had been struggling as Beijing cranked up pressure to get the ship out of Ayungin.

Every step and move my news team and I made inside BRP Sierra Madre were closely watched. Not only were we careful about navigating the decomposing floors, but also the navy intelligence officers on our heels. Our interviews with the personnel manning the ship were guarded — and so were their answers.

A scrape or cut from the crisp rust nibbling at every inch of the walls looked like a tetanus waiting to happen, but the view of the sky outside matching the blue color of the endless sea was most consoling.

Only the huge plastic containers used to collect and store rainwater were not wasting away. Fresh water rations came with us that day along with a good supply of canned foods, coffee, sugar, toiletries, rice, and other essentials.

The 100-metre (328-foot) BRP Sierra Madre was home to this small contingent of Marines keeping watch over Ayungin. Their families live in Palawan province, just 105 nautical miles west of the Shoal.

On the dilapidated deck of the ship was evidence of the navy’s determination to survive. Vegetables such as string beans, squash, okra, bottle gourd (upo), bitter melon (ampalaya), and sweet potatoes were thriving in a potted garden with the soil brought in from Balabac island in Palawan.

Traces of the Navy’s rewarding pastime could be seen hanging everywhere. Left to dry under the sun were the different kinds fish they had caught. A good portion of their catch had already been packed as “pasalubong” for their families on the mainland, and for the NAVSOG team as gifts for the boat ride home.

The tour of duty of the troops who replaced the outgoing personnel on BRP Sierra Madre began that day, hanging on to the hope that they survive while their supply lasted.

As to China’s recent claim of an alleged promise by a Philippine official to tow the BRP Sierra Madre out of Ayungin Shoal, one navy “frogman” said it was out of the question.

“Towing it now only means giving up even before the game is over,” he explained “The ship may give way eventually. But not the soldiers in it. “

(Charmaine Deogracias is a fact-check editor and head of the Social Media Strategy, Promotions and Communications at VERA Files. She is based in Toronto, Ontario, Canada where she completed her post-graduate programs on Social Media, and Public Relations and Corporate Communications. Formerly, she was a reporter for Japan’s NHK TV)