Even as the country grappled with new strains of Covid-19 last year, the Duterte government’s drug war continued to claim more lives at the average rate of three deaths every two days.

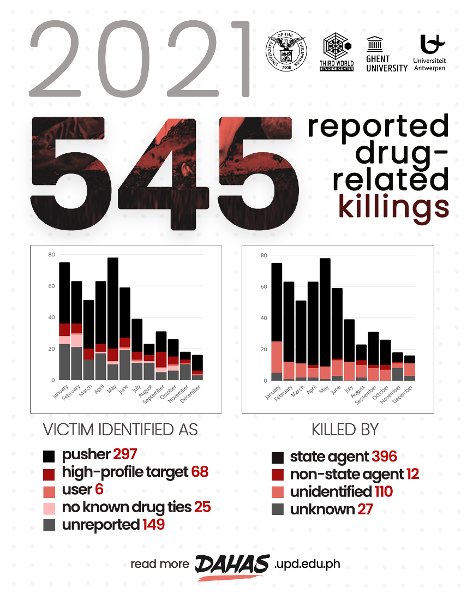

Data collected by the Third World Studies Center of the University of the Philippines Diliman showed that in 2021, the second year of the pandemic, 545 people were killed in the bloody campaign. This was 84 more than the total in 2020, or an 18 percent increase.

Of the 545 drug-related killings, 392 (or 72 percent) were recorded within the first half of the year. The number peaked in May, reaching a daily average of 2.52 deaths and slowly tapering off in the following months as leadership of the Philippine National Police (PNP) transitioned from Debold Sinas to Guillermo Eleazar.

The non-stop drug-related killings affirm President Rodrigo Duterte’s defiance of criticisms of his brutal policy which, according to human rights groups, have resulted in the death of at least 20,000 people since 2016. The government, however, admits to only over 6,000 of such killings.

In his first address to the nation this year, Duterte showed no remorse declaring, “I will never apologize for the deaths.”

Hotspots for drug-related killings spread out of Metro Manila

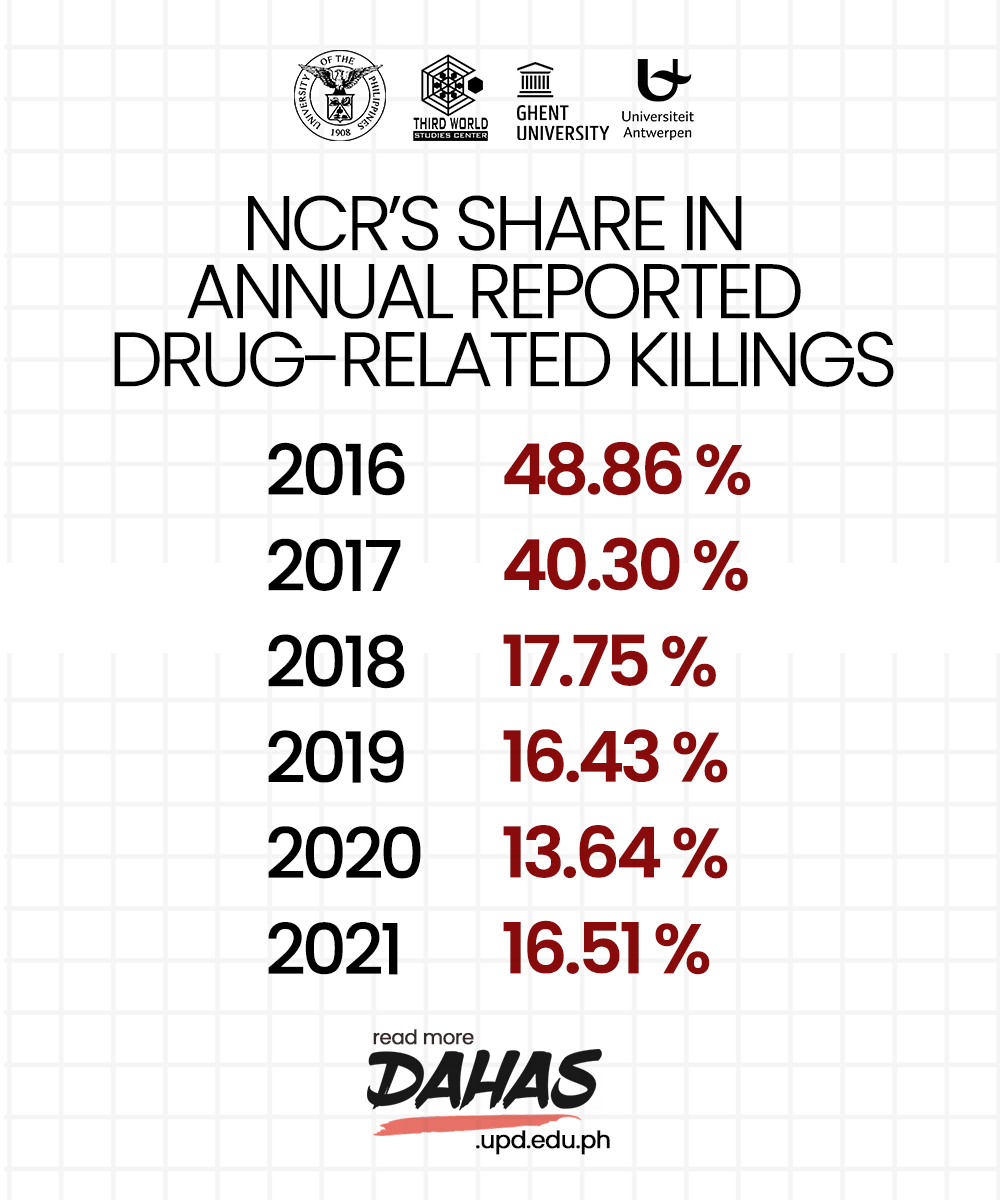

According to the ongoing study by the UP Third World Studies Center in partnership with the Department of Conflict and Development Studies of Ghent University and Antwerp University, the National Capital Region (NCR) remained the top killing hotspot in the country last year, with a 17 percent share of the total number of deaths.

NCR was followed by the provinces of Nueva Ecija, Bulacan, Cavite, and Cebu. As the numbers dwindled by the second quarter of 2021, Cebu, Negros Occidental, Davao Del Sur, Camarines Sur, Camarines Norte, and South Cotabato emerged as the top killing spots in the latter months of last year.

In 2016 to 2017, the first couple of years of Duterte’s drug war, two in five drug-related killings occurred in Metro Manila. A noticeable shift happened in 2018 when only one in five deaths were in the capital region, a trend that has continued to this day.

PNP and PDEA lead in the drug war kills

As in previous years, killings by law enforcement agents, particularly the PNP and the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) constitute the large majority of incidents involving casualties. Out of 545 fatalities, 396 or 72 percent were committed by state agents, often in buy-bust operations during which the target allegedly resisted arrest, fired at the enforcers which forced them to shoot back and “neutralize” the drug suspect.

This usual “nanlaban” narrative has raised suspicions as to its truthfulness, especially when countered by witness accounts. The International Criminal Court (ICC) has cited this as basis to open an investigation in the Philippines, stating that “the accounts of eyewitnesses and other sources such as video footage, show that in many cases the narrative of a buy-bust operation is not credible, and police killed the victims in cold blood.”

In 2021, hard evidence to support these suspicions once again emerged when in Bukidnon, a police officer in plainclothes was caught on camera firing a gun at a drug suspect, then planting a gun beside the fallen body. Before the video surfaced, the incident report reflected an exchange of fire between the two. Five days after the incident, the police officer involved died from fatal head injuries he sustained in a car accident.

From January 1 to November 30, 2021, PDEA’s Real Numbers PH page placed the number of persons who died in anti-drug operations at 210. UP researchers, collecting data from news reports for the same period, registered 338 killings resulting from planned raids.

The drug war also saw a rise in the number of vigilante-style executions of suspected drug personalities in 2021. Of the149 such killings, 110 were carried out by unidentified assailants (e.g. riding-in-tandem), 12 by non-state agents (identified private individuals), and 27 by unknown assailants.

Unidentified attackers in incidents with no witnesses are associated with “body dump” victims whose mutilated corpses are left sprawled in the streets or placed in secluded areas, sometimes bearing a placard implicating them in the illegal drug trade. While body dump cases were most prevalent in the early years of the bloody campaign, they continued to persist last year when 17 cases were registered, up by six from 2020.

On March 12, 2021, CCTV footage recorded two men clad in black jackets as they got off a white Innova along Francisco Street, Brgy. 75, Caloocan City. With another man serving as look out, they dropped off the corpse of a certain “Nap,” an alleged drug pusher. The dead man’s bloody head was covered in packaging tape, his feet bound, and a cardboard box hung around his neck with the words, “Tulak ako! Wag tutularan susunod na kayo!” (I’m a drug pusher, do not emulate or you’re next.)

Drug pushers remain top casualty in the drug war

The fight against illegal drugs supposedly employs a two-pronged strategy to effectively target street-level peddlers and users, while also going after high-value targets involved in the large-scale manufacturing and distribution of illegal drugs. The various PNP chiefs that oversaw its implementation repeatedly vowed to set their focus on the “big fishes” of the illegal drug trade. But the distribution of drug-related killings is slanted against small-time dealers and users.

In 2021, low-level personalities, particularly drug pushers, continued to bear the brunt of the violence. High-profile targets killed make up only 68 or 12 percent of total deaths. Pushers, on the other hand, constitute 297 or 54 percent of the fatalities. While six were reported to be drug users, the involvement of 149 others in the illegal trade were not specified in the news reports as they were simply tagged as drug suspects.

Drug war claims innocent victims

There were 25 individuals killed in drug-related encounters but were reported to have no links to the narcotics trade whatsoever. These included instances involving “mistaken identity

and cases of “collateral damage,” victims who were not involved in illegal drugs but died in encounters where they were not the main target. Eleven such cases were recorded in 2021, which was five more than the preceding year.

One of these drug-related encounters was a fatal shooting incident in Laguna where multiple gunmen entered a shop and killed four men but only one was involved in illegal drugs. In another incident, an unidentified woman was caught in the crossfire between state armed forces and two most wanted criminals in Tawi-Tawi who were responsible for the entry of illegal drugs from Malaysia. Six more were killed in cases of mistaken identity, including five who were slain in the infamous misencounter between elements of the PNP and PDEA on Commonwealth Avenue, Quezon City on 24 February 2021.

Most drug war kills have prior criminal records, known to the police

Data also show that 350 or most of the victims had been investigated for their links to the illegal drug trade. Of these, 78 were identified because of their previous arrest, conviction, or surrender for drug-related crimes. Over the past years, these victims have attested to the threats they faced after serving time in jail or going through rehabilitation, including becoming targets of unidentified assailants. One such victim was Jundel Diaz whose lifeless body was found in a sack on April 16, 2021 in Negros Occidental, his head wrapped in duct tape and his hands tied. Diaz had earlier surrendered to authorities for his illegal drug activities.

In some instances, ex-convicts were shot dead immediately after their release from prison. Reynaldo Arsenal, 48, spent nine years behind bars for drug-related charges before being released on bail. Just hours after being granted temporary liberty, his vehicle was ambushed and he was shot by unidentified assailants. Similarly, Flora Mae Yuson, who had likewise been recently released from prison, was shot on July 16, 2021 by motorcycle-riding gunmen. She had a months-old baby in her arms.

The drugs watchlist, which critics have dubbed as a “kill list”, remains operational. Included on that list were 73 victims and 51 of them were killed by law enforcement agents. The rest were either killed by unidentified or unknown assailants. Notably, a handful of the victims were former and current local officials such as Libungan mayor Christopher “Aming” Cuan. The mayor, who was on one of Duterte’s narco-lists, and his driver were gunned down by unknown attackers on January 11, 2021. Links to the drug trade of eight victims were sourced from informants, and 10 from unidentified sources. Connections of 88 victims to the drug trade were determined post-mortem or at the scene of the incident.

Drug war downs mostly male victims

A majority, or about 87 percent, of the fatalities in the drug war were male, 23 were female, and. nine were unreported. Because of the limitations of gathering data from news reports, a huge ratio—320 out of 545 victims—also had unreported ages. Of those which had that detail, seven were aged 60 to 69, 24 were between 50 to 59 years old, 94 were between ages 30 to 39, 41 between 20 to 29 years old, and four were teenagers.

One of the victims, Johndy Maglinte Helis, was 16 years old and was in handcuffs when he was allegedly shot dead by the police. He was said to be pleading for his life. The Internal Affairs Service of the PNP later freed the 10 police officers from all liability for the death of the young man.

More foreigners killed in the drug war in 2021

As was earlier pointed out, foreigners have also been casualties of Duterte’s drug war. In 2020, the UP researchers recorded two deaths of foreign nationals (one Chinese and one Nigerian). The year 2021 saw an uptick —15 in all —11 of them Chinese, and the rest were Korean, Nigerian, Malaysian, and Pakistani. Of the total, eight were high-value targets, and the majority were killed by state-agents in planned operations.

On May 10, 2021, a Chinese national who just got out of detention in Camp Bagong Diwa on illegal drug charges was killed inside a taxi by motorcycle-riding men along Doña Soledad Ave. Later in the year, four more Chinese nationals—Cai Ya Bing, Erbo Ke, Huang Guldong, and Wuyuan Shen—were killed by PDEA agents in a drug bust in Angeles City, Pampanga which yielded 38 kilos of crystal meth with an estimated street value of P262.2 million.

Concern about the human rights violations in the ongoing drug war have resulted in two investigations. One was initiated by the International Criminal Court (ICC) which found reasonable basis that crimes against humanity have been committed under the bloody campaign. However, the probe was temporarily suspended after the Philippine government filed a “deferral request” in November. The ICC is also hard-pressed by the government’s unyielding stand of non-cooperation with its investigation.

Domestically, there is an ongoing investigation carried out by the Department of Justice (DOJ), scrutinizing only 52 deaths in anti-drug operations. The review panel has released its observations, noting various lapses such as victims testing negative to paraffin tests, fingerprint tests indicating that a victim did not hold a firearm, and “employment of excessive use of force” indicated by multiple gunshot wounds in the victim’s body. The National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) is next in line in assessing the DOJ’s findings before charges can be filed against police officers.

Will the drug war keep on killing?

With election season at hand, the illegal drug problem is expected to be one of the key policy issues that presidential candidates need to address during their campaigns. Most of the top candidates vying for the position favor continuing the drug war but with modifications. Labor leader Leody de Guzman, Manila Mayor Isko Moren, and Vice President Leni Robredo have all expressed their support for the ICC’s probe, while Ferdinand Marcos Jr. is against it.

Robredo, Lacson and Marcos Jr. agree that the current drug war has prioritized the law enforcement aspect of the campaign, and there is a need to strengthen prevention and rehabilitation. Senator Manny Pacquiao and Moreno favor continuing the fight against illegal drugs, but stress the need to uphold human rights in the implementation.

With less than six months left in Duterte’s term, whoever takes the seat of power next will have to deal with the undisputed spate of killings under the brutal policy on illegal drugs as building efforts to exact accountability remains a pivotal task. The continuously rising death toll must be matched with the constant and tireless vigilance of documenting the cases of those who have fallen victim to the unrestrained violence.

Only then can justice begin to be served.

(Nixcharl C. Noriega and Larah Vinda Del Mundo are researchers at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. Joel F. Ariate Jr. and Elinor May Cruz provided research assistance. This piece is part of the on-going research project, “Violence, Human Rights, and Democracy in the Philippines.” The project’s output can be accessed at dahas.upd.edu.ph. For the latest in the running count of the reported drug-related killings in the Philippines, follow @DahasPH on Twitter.)