By ARIEL SEBELLINO

FOR four days in February 25 years ago, Filipinos enthralled freedom-loving people all over the world when they stalled military tanks with nothing but rosaries and roses and the determination to win back the freedom taken from them by a strongman who ruled the country for more than 20 years.

It was a gripping demonstration of “People Power,” which started in the afternoon of Feb. 22. By evening of Feb. 25, then President Ferdinand Marcos, his family and cronies fled the country, transported by a United States C-130 plane to Hawaii.

Two veteran journalists belonging to what was then referred to as the “alternative press” in contrast to government friendly establishment press, recalled how their newsrooms and coverage were put to test and their careers defined by an event that changed the course of the country’s history, politics, culture and society.

Lourdes ‘Chuchay’ Fernandez, then editor-in-chief of Ang Pahayagang Malaya (Filipino term for “Free”), sees the four-day EDSA experience as the culmination of several challenging and dangerous years for the “Mosquito Press,” referring to the small publications critical of the Marcos dictatorship.

Three years earlier, Malaya’s sister publication, We Forum, was raided, its printing press padlocked and its publishers, editors and columnists led by Jose Burgos Jr. were arrested and jailed for publishing a series of articles on Marcos’ fake medals.

Malaya, which was registered as a Tagalog publication, shifted to English and took up the truth crusade started by We Forum.

Fernandez, now editor-in-chief of Business Mirror, recalled that as soon as then Defense Secretary Juan Ponce Enrile and then Philippine Constabulary Chief Fidel Ramos declared their break from the Marcos government, Malaya set up a composite team, separate from its office on West Avenue in Quezon City, that could run a remote newsroom in case the newspaper office was raided again.

From their safehouse, her team would produce half of the issue for the next day, transcribing quickly the historic Enrile-Ramos press conference on their “breakaway,” among other articles. At one point, she remembered they were instructed to hurriedly return to “Base” (the Malaya office on West Avenue) on the third day, when it was prematurely announced that Marcos had left Malacanang. When the report turned out to be false, they hurriedly unpacked their gear and resumed operation at the safehouse.

Since people were so hungry for stories about the unfolding events at EDSA, Malaya sold out one million copies daily—unprecedented in the history of newspaper publishing in the Philippines.

“EDSA, to my mind, is not just four days in February,” Fernandez said. “It was a logical culmination of years of anger and despair, of struggle and even of constant disagreement among allies, of battles won and lost along with fortunes, and of an abiding faith of a people in a Supreme Being who walked with them in their road to Calvary, and faith as well in a democracy that they knew was theirs if they but won it back.”

Vergel Santos, chair of the editorial board of BusinessWorld, was then executive editor of the newly revived Manila Times during those historic days of February.

Manila Times was the leading newspaper before Marcos declared martial law on Sept. 21, 1972. It was closed down by the government and its owner Joaquin “Chino” Roces was arrested and detained. Roces never re-opened Manila Times during the Marcos regime.

It was only two days before the Feb. 7, 1986 snap presidential election that Manila Times was reopened with its office in Quezon City, a few kilometers away from the center of the EDSA Revolution.

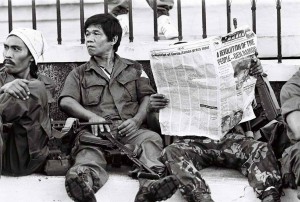

“I did make time, between editions, to visit EDSA and get an actual feel of it—one just had to,” Santos said. “Still, I needed to fight the compulsion and concede that my role at the moment as a newspaper editor was to ensure that the news was captured first hand by my reporters and set by my editors in irrevocable print under my direction.”

Santos said that on the second night of the uprising, the sight of soldiers in their vicinity made them fear an imminent crackdown. He said their impulse at that time was to smuggle Amado Doronila out of the office and find him a safehouse.

A former martial law detainee, Doronila had come home from exile in Australia, where he had worked for the Melbourne Age, to join Manila Times.

Every day on page one, Doronila wrote a political commentary that predicted the impending downfall of the Marcos dictatorship. For Santos, Doronila’s daily piece was obviously a voice Marcos could not afford to suffer at that time.

“The point of no retreat had been reached, and EDSA was the battleground: It was Cory or Marcos, democracy or dictatorship,” he said. “As for Doronila and the Times, they were no more than footsteps to the history being made.”