EDSA, from my perspective as then editor-in-chief of the “Mosquito Press” pioneer Ang Pahayagang Malaya of Joe Burgos Jr., broke in the early afternoon of Feb. 22, 1986 when I received a phone call from Malaya’s Malacanang reporter, Butch Fernandez, who said he had heard the distinct “ting-ting-ting” of the teletype machine that receives wire-agency news feed at the Palace press room, indicating an urgent, big development.

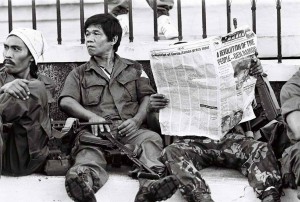

The news bulletin mentioned uniformed men on helicopters having landed at the Quezon Memorial Circle, which it turned out were the “Cagayan 100” meant to augment troops loyal to Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile, who was breaking away from Mr. Marcos.

Indeed, the other reporter who was inside the Palace press room at the time and read the wire bulletin was veteran defense reporter Alex Allan, then with the Philippines Daily Express. His instincts told him the troop movements were related to some upheaval in the military, and he alerted Butch about this.

I alerted Joe about the wire news bulletin, and he replied, “That must be it. That must be related to the big developments that we should be tracking.” He explained that his sources had hinted a few days ago that something was afoot, without going into specifics.

Butch said the Palace reporters were told there might be a press briefing, but no further details were given. Joe instructed him to stay put. Meanwhile, Joe made some calls. Soon after, our young defense reporter, Vittorio “Vot” Vitug, called to alert us that something was, indeed, going on at Aguinaldo and Crame.

Soon events quickly unfolded, as most EDSA readers must now be familiar with. Later in the afternoon of Feb. 22, Joe received a call (he said it was from Louie Beltran of the Philippine Daily Inquirer), who asked if he had heard about a report that the forces of Armed Forces chief of staff Gen. Fabian Ver had orders to arrest dozens of opposition leaders, as well as journalists in the Mosquito or Alternative Press, and haul them off to some detention facility on an island. The two friends counseled each other to take precautions and stay in touch.

Now, that was hard at the time because we only had land lines—no texting, no tweeting, no mobile phones. In Malaya’s case, we were lucky that Joe had the foresight to request a private company for a demo of handheld radio units, which we had used for the coverage of the snap elections. The units were still with us, and Joe instructed me to “disengage in 10 minutes” from the West Avenue offices of Malaya, and take a composite team that, he said, can run a remote newsroom—in case, he said, “this place is raided and we are arrested.” His only marching order: Keep publishing as long as you still can, so people will know what’s really going on.

He and his wife, Malaya’s real “commander in chief” Edita (Note: Edith would later become the face of the Mater Dolorosa of the disappeared, as she leads a lonely war, as a widow, to find her son Jonas, abducted by the military), had very quickly made preparations to make sure the printing presses that had so bravely printed Malaya during the dictatorship would continue to do so in this still unfolding crisis. Advance payments were made, and a system for securing materials—and people—quickly put in place.

Joe and Edith were so organized that part of the contingency was that if for some reason a printer was raided, threatened, or could not print, some others would take up that printer’s share of copies to be printed. This was crucial because at the time, we were printing about half a million copies in all, spread across three daily editions.

Thus it was that soon after issuing his marching orders, Joe bundled us off in one of the company vans, to a safehouse several kilometers away. With me were our news editor Yvonne Chua, Sports subeditor Noli Cortez, editorial-production coordinator Tess Molina and a few others—two encoders, two layout artists, a proofreader, a photographer, among them.

From the safehouse Yvonne and I and our team would produce half of the issue for the next day, transcribing quickly the historic Enrile-Ramos press conference on their “breakaway,” among other articles. The paste-up pages were picked up by drivers and messengers working round the clock, to be reunited with those produced from “Base” (the Malaya office on West Avenue), and then all ending up with the printers.

We kept in touch with Base via our handheld radio. Remaining on West Avenue were Joe, managing editor Noel Albano, Joy de los Reyes (the current editor in chief of the paper), among others. At one point, we were instructed to hurriedly return to Base on the third day when a premature report of Marcos fleeing the Palace broke out. Of course, we just as hurriedly unpacked our gear and set up again at the safehouse on hearing later that the dictator was still at Malacanang.

To be sure, our four-day experience at EDSA was just the culmination of several exciting and dangerous years in the Mosquito Press. I still recall what Cory Aquino had said in June 2003 in a tribute to Joe Burgos (then stricken with cancer). She had thought, in the first dark months of martial law, that no one remained outside Marcos’ prison who could help his victims—especially when her husband Ninoy and Jose “Pepe” Diokno were taken by the military from Fort Bonifacio and kept incommunicado in what she later learned was Laur, Nueva Ecija.

But then, she added, “one day there came Joe Burgos.”

The multi-awarded police reporter of the Manila Times chain had founded in April 1977 the WE for the Young Filipino (WE Forum) to test the waters as the first non-crony-owned publication. It didn’t take long before WE Forum would become a very popular trailblazer, so alarming the minions of the dictator that it was raided and shuttered on Dec. 7, 1982. Joe, his father and two brothers, and several columnists and writers were hauled off to prison. They were released two weeks after only because of a massive international outcry.

Just a little over a month later, with a sedition case and threat of re-arrest hanging over his head—and over the advice of his lawyers (among them were Joker Arroyo, Jojo Binay and Bobby Tanada)—Joe put out Malaya, WE Forum’s Filipino “twin”— but this time as an English-language weekly.

Joe’s Malaya would have its shining moment on Aug. 21, 1983, and the days soon after, because it published many events and pronouncements that Joe’s colleagues and friends in the so-called crony press were restricted from using—though not for lack of trying.

The years 1983, 1984 and 1985 would see Malaya—and later WE Forum, which won its case in the Supreme Court in December 1984—mirroring the historic unfolding of a protest movement that was politically diverse but eventually united in a common effort to end a dictatorship and restore democracy.

EDSA, to my mind, is not just four days in February. It was the logical culmination of years of anger and despair, of struggle and even of constant disagreement among allies, of battles won and lost along with fortunes, and of an abiding faith of a people in a Supreme Being who walked with them in their road to Calvary, and faith as well in a democracy that they knew was theirs if they but won it back.

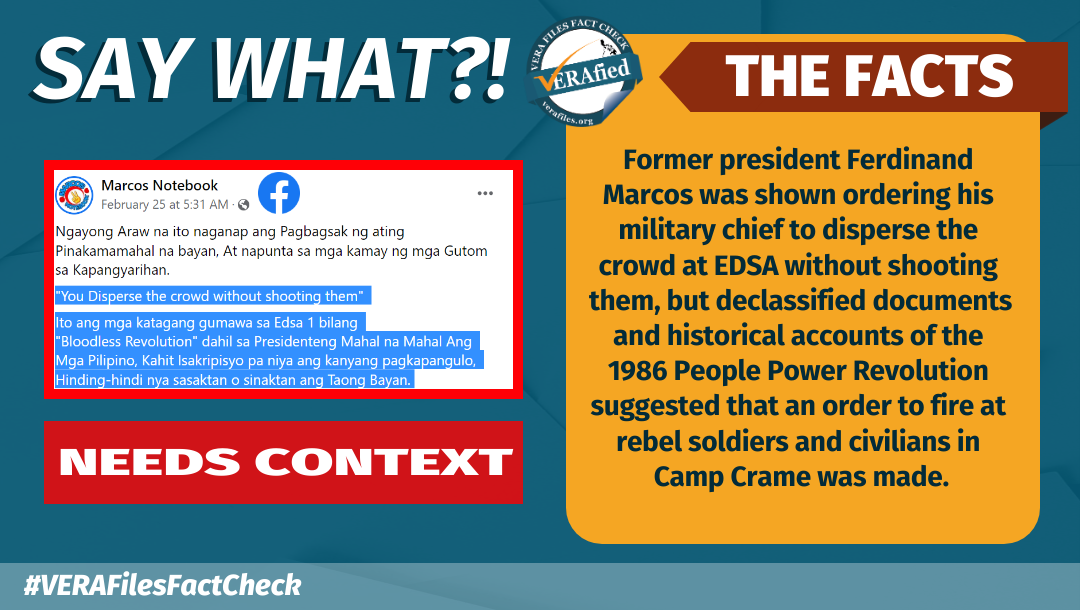

Now, 25 years later, I’d choose not to join the EDSA-bashing of some who say it accomplished nothing because many people are still poor, that many in government and the military are corrupt, that political leaders and institutions and groups are still so fractious. I’d rather choose to consider where we might be, if EDSA didn’t happen. Who knows, maybe we’d be envying the events in Egypt and copying from the democracy playbook of other nations.

Of course, some over-reaction, in the post-Marcos era, did not help our cause—and I’ve always maintained we should be fair in citing Marcos’s clear accomplishments where they mattered, i.e., in his vision and commitment to craft a road map in energy self-reliance at a time when we were almost exclusively hostage to the vagaries of the global oil market.

In the past quarter of a century, much of the world has changed as well, and to me it doesn’t matter anymore if the West opts to ignore the Filipinos’ example as democracy movements subsequently took root in so many other places on the planet, and people asserted their sovereignty and self-determination. How many of those liberation movements were truly inspired by EDSA? We will never really know, and it really doesn’t matter now.

At the end of the day, we simply rejoice in their newfound freedom, and pray they be spared from much of the mistakes we made along the way, from Day One after liberation. This week, we pray for a peaceful, rational transition in several places marked by upheavals, even as we keep trying to make it all right for our nation, 25 long years later.

(Lourdes Molina-Fernandez is now editor in chief of BusinessMirror. Yvonne Chua is now a trustee of VERA Files. Another trustee, Chit Estella, used to be Malaya’s senior reporter. VERA Files trustee Ellen Tordesillas, a pioneer at Malaya, still writes a column for the paper.)