By LUZ RIMBAN

BANGUED, Abra—Most Filipinos may have forgotten what the original People Power Revolution was all about, but the spirit of EDSA lives on every day in this mountainous northern Luzon province.

The Concerned Citizens of Abra for Good Government (CCAGG), an anticorruption, pro-transparency and pro-accountability organization that celebrates its 25th anniversary on Feb. 25, embodies that spirit.

The group could very well be considered the Philippines’ pioneer watchdog group. For the past 25 years, it has been evaluating whether taxpayer money is spent wisely in government projects, sitting in bids and awards committee meetings, helping implement government programs, and keeping people informed about their rights and obligations.

The CCAGG has, in fact, won numerous local and international awards for keeping an eye on government-funded infrastructure projects such as roads, bridges, irrigation systems and deep wells.

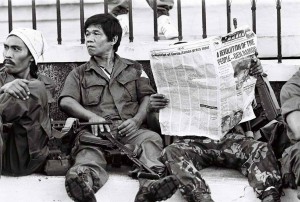

But it all started in the heady days of EDSA 1 when 100 or so Abrenians, who then comprised the local chapter of the National Citizens’ Movement for Free Elections (Namfrel), decided they needed to evolve.

From monitoring elections just once every few years, they agreed to take on the continuous task of monitoring the fulfillment—or failure—of election promises.

“We were actually in the midst of an organizational meeting in Bangued when news of the EDSA Revolution reached us,” said CCAGG chairperson Pura Sumangil. “We had mixed feelings and were anxious for the safety of everyone in Manila.”

By then, the group was certain there was more they could do together. Sumangil, a retired teacher at the Divine Word College here, said their collective experience as election watchdog resulted in their “discovery that something novel and good could be attained when people, believing in a cause, bind themselves to work together.”

On Feb. 25, the day Aquino was inaugurated president in a hurriedly put-together ceremony at Club Filipino in Greenhills, the CCAGG was born.

Sumangil and her companions did not yet have a name then, and it was only in the succeeding weeks that they decided on “Concerned Citizens of Abra for Good Government,” which reflected the group’s composition. They were from different sectors and economic classes, but they had a common compassion for their province, which counts among the poorest in the country.

During Aquino’s term, government recognized the contribution of people’s groups and nongovernment organizations in restoring democracy. These organizations tried to live up to a key EDSA ideal, now long forgotten but at the time a buzzword: people empowerment.

That ideal eventually found its way into the 1987 Constitution. Article XIII, Section 6 states, “The right of the people and their organizations to effective and reasonable participation at all levels of social, political and economic decision-making shall not be abridged.”

This ideal became reality when the Local Government Code was passed in 1991 and mandated local government units to “promote the establishment and operation of people’s and nongovernmental organizations to become active partners in the pursuit of local autonomy.”

Aquino took “people empowerment” seriously. Soon after she became president, the National Economic and Development Authority invited NGOs like the CCAGG to take part in monitoring government projects through a program called the Community Employment and Development Program.

The project required these organizations to watch the implementation of projects such as farm-to-market roads, hanging bridges, spring developments, health centers and school buildings.

The CCAGG accepted the invitation and signed a memorandum of agreement with the Budget Department and NEDA, which trained its members on the mechanics of monitoring and reporting, and provided them with a list of projects to be monitored.

For its part, the CCAGG called on Abrenians to report on how well—or how badly—the projects were being implemented.

“When project implementation finally started, the people’s interest was very much felt. The implementing agency resented this. They talked down to us and asked what do we know or understand of their technical work like road building or irrigation construction?” Sumangil said.

One of these agencies was the Department of Public Works and Highways, which people have always perceived to be among the most corrupt in the country. CCAGG members had difficulty dealing with DPWH personnel, who refused to give them information about projects.

That all changed one day in 1987, however, when the DPWH office in Abra advertised its supposed accomplishments in the regional newspaper, NorLuzonian Courier. It declared several roads and bridges 100 percent finished.

The ad caught the attention of CCAGG members who knew for a fact that some projects the DPWH reported completed remained unfinished. The group asked then Public Works Secretary Vicente Jayme and the DPWH central office to verify the accomplishment report by “sending someone who could not be bribed.”

That was CCAGG’s first victory. The case caused the suspension of 11 DPWH engineers and later the filing of cases against them.

On Feb 15, 1988, just two years after the group came into being, the CCAGG was chosen “Outstanding NGO in Region I for Community Service.” Its members traveled to Manila to receive the plaque of appreciation, handed to them by no less than President Aquino herself.

Over the years, CCAGG has gone beyond tracking the construction of roads and bridges. In 1996, for instance, former Ambassador to the Vatican Howard Dee, then chair of the Government Panel in peace talks with the National Democratic Front, asked the CCAGG to monitor whether both the Armed Forces and the New People’s Army honored a holiday armistice. The group eventually helped provide livelihood training to rebel returnees.

The CCAGG also helped other NGOs implement projects on biodiversity and accountability, and is working closely with local government units on empowering other people’s organizations.

In 2001, CCAGG partnered with the Commission on Audit for a “participatory audit” in which COA and CCAGG jointly scrutinized the implementation of projects.

Partly because of this, Abra today is a far cry from what it was 25 or even just 10 years ago in terms of infrastructure. “Marami nang nagbago sa Abra (A lot has changed in Abra these days),” said engineer Irene Bringas, who used to head CCAGG’s monitoring team.

Bringas points to bridges that lay unfinished for decades but have finally been completed. One of these is Soot Bridge, which connects the towns of La Paz, Danglas and Lagayan to Bangued, the capital. The bridge was one of those included in the DPWH accomplishment report in 1987. It was finished only in 2003.

Another is the Calaba Bridge, which spans the Abra River, and is considered one of the Philippines’ longest bridges. Before the bridge was completed last year, people and vehicles crossed the river on barges. It is now an important link not only to La Paz, Danglas and Lagayan but also to the provinces of Ilocos Norte and Cagayan.

In a province where it can take a traveler a whole day’s hike to reach the farthest town, it would be an understatement to say that roads and bridges are important in Abra. It’s a sentiment common in other parts of the Cordilleras where having a road or a bridge could spell economic empowerment.

In recent years, the CCAGG has helped replicate its experience in other Cordillera provinces and elsewhere in the country. The Kalinga Apayao Religious Sector Association (KARSA) is using CCAGG as a model watchdog group. The CCAGG is also training NGOs in the Bicol region in the technology of keeping an eye on government.