By MARIA FEONA IMPERIAL

THE attack on a Lanao del Sur gubernatorial bet in an ambush early Saturday morning did not make it to the first election-related violence (ERV) report released recently by the Commission on Human Rights (CHR).

If it did, it would have raised to nine the incidents of ERVs in the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), the same number in the Zamboanga Peninsula and the highest in the country recorded so far in connection with the upcoming national and local elections.

The CHR’s April 8 report compiled ERV incidents from all over the country from June.

Half or 26 out of 49 reported ERV incidents occurred in Mindanao.

Of this, 23 victims were killed or wounded by gunshot, despite the gun ban and checkpoints implemented by the Commission on Elections on January 10.

The report was produced under Bantay Karapatan sa Halalan (BKH), whose 10,000 human rights advocates and poll watchdog volunteers seek to monitor human rights violations before, during and after the elections.

Launched in December, the BKH is a collaborative project of the CHR, the Philippine Alliance of Human Rights Advocates (PAHRA) and electoral reform group Legal Network for Truthful Elections (LENTE).

It culled data from news articles, validated election-related incidents (VERIs) from the police, and case documentation from civil society organizations.

Hover on the interactive map and chart for details.

Aside from Lanao del Sur, eight other provinces have made it to the election watchlist areas of the Commission on Elections and the Philippine National Police: Abra, Nueva Ecija, Lanao del Norte, Pangasinan, Masbate, Negros Oriental, Maguindanao and Western Samar.

7 poll-related deaths in Calabarzon in a month

While Mindanao has the most number of ERVs, killings have been more frequent in Calabarzon, particularly in Batangas and Laguna, where seven incidents took place in just a month, according to BKH’s own monitoring.

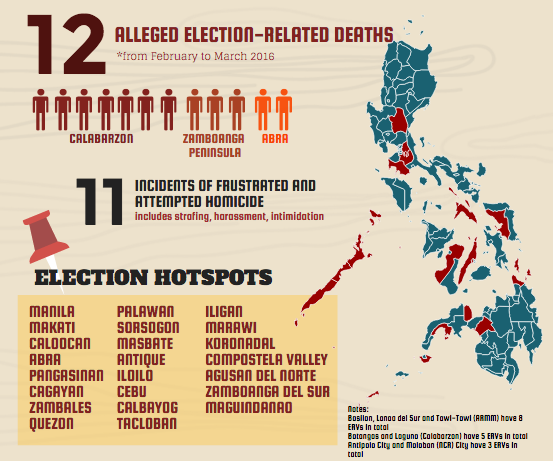

From February to March, the group recorded 12 election-related killings: seven in Calabarzon, three in Zamboanga Peninsula and two in Abra, where politics fall in the hands of two contending clans: the Seares-Luna and Valera-Bernos families.

Meanwhile, 11 election-related frustrated homicide charges were reported from January, mostly from Zamboanga region.

Directed at incumbent officials, candidates and supporters, these assaults include incidents of strafing, intimidation, harassment and the proliferation of loose firearms in Sorsogon, Zamboanga del Sur, Basilan, Sulu, Tawi-Tawi and Zamboanga City.

Criminal charges, however, can only be filed after the incidents have been investigated and validated, the CHR said.

“These violations create an atmosphere of fear among the electorate and impede the efforts of the human rights community towards achieving peaceful, transparent and credible elections,” CHR Chair Jose Luis Martin Gascon said.

Warlike maneuvers in violence-ridden Mindanao

Marawi City Mayor Fahad Salic, the victim in Saturday’s ambush, was shot thrice, dodging at least 31 bullets, which the local police officer described as “minor” and dismissed as “all slight wounds.”

The mayor is no stranger to violence-ridden elections. And violence is not new to Mindanao where the culture of “rido” or clan wars account for most ERVs. Backed by their own private armies and warlord allies, feuding political families in Mindanao get back at each other to seek revenge and secure power.

Salic garnered a landslide victory in the 2010 presidential elections, after he resorted to distributing pre-shaded ballots and other warlike maneuvers, VERA Files reported in its book Democracy at Gunpoint.

On election eve, the local election officials ordered the transfer of precincts from the tightly secured Mindanao State University gym to schools in areas farther than the public eye.

Hours before voting opened, a grenade and two other improvised explosives were blasted near the gym, only to justify the transfer.

Bomb blasts, carnages and other warlike tactics no longer make a cause for alarm as election nears in Lanao del Sur, a minefield of intense political rivalries, warlordism and clan conflicts.

For the province’s well-entrenched kingpins, the deal is to come out alive.

Kidapawan incident under CHR probe

Meanwhile, Gascon clarified that the report did not include the violent dispersal in Kidapawan, Cotabato which is still under investigation.

On April 1, some 6,000 farmers protested on the streets for the government’s failure to assist those starving from the effects of drought or El Niño. According to reports, police fired on the protesters.

While there have been insinuations of the event being election-related, Gascon said as of now, it is being treated as an issue of right to food and freedom of assembly.

Acts of extortion, negative campaigning

A spate of harassment acts, mostly in Central and Southern Luzon, by political rivalries and other non-state armed groups have been reported. These include extortion by those requiring permits to campaign.

In some parts of Metro Manila, some candidates have resorted to negative campaigning, which is seen to depress the level of electoral discourse among voters.

“It leads people to believe that none of the candidates are eligible for election,” the CHR report said.

Fearing reprisal, witnesses refuse to report ERVs

Beyond assaults and killings, the results of the monitoring included violations of the right to vote and participate in public affairs, as well as right to information and freedom of movement.

Still, candidates are running unopposed in a considerable number of areas. Most belong to incumbent political families, if not are the incumbent politicians themselves, the report said.

Voters are sometimes forced to accept money, just so that they will not be identified as belonging to or supporting the opposing candidate, according to the report. In areas where candidates run unopposed, less money is distributed among voters.

Fearing for their safety, most witnesses refuse to come forward and report incidents, regardless of whether or not they have benefitted from the candidate in some way.

Anonymity, Gascon said, is one of the reasons amid the heaps of documented reports on ERVs, only very few have been charged with criminal offenses.

Volunteers not enough to monitor overseas voting

Meanwhile, for overseas voting, Gascon admitted they don’t have enough volunteers to monitor incidents of ERVs and vote-buying.

Volunteers, who are either trained by the CHR or citizen volunteers, are concentrated in election hotspots. These hotspots have been picked based on the frequency and degree of election-related HRVs committed in the previous polls.

Overseas voters, however, are free to become citizen volunteers of the BKH.

CHR warns public of cyberbullying

The CHR has also expanded its coverage of human rights violations to include cyberbullying and harassment in social media.

There has been a noticeable increase in malicious and below-the-belt statements in manifesting threats against people expressing their political opinions, Gascon said.

“Dahil sa social media, maraming pwede magtago. (Due to the nature of social media, many people find it easy to hide.) They now think that they are free to threaten others,” he said.

But there needs to be “a degree of civility in (social media) interaction,” he said.

Asked how they are going to track incidents of cyberbullying, Gascon, however, could not provide a clear proposal, except for coordinating with civil society organizations.

The BKH will release updated reports on ERVs every Monday before May 9. It also encourages the public to engage in providing crucial information in monitoring human rights violations, whether as citizen volunteers or witnesses.

Lawyer Rona Ann Caritos, who heads LENTE, said witnesses shall be afforded protection through their lawyer and paralegal members, as well as from the CHR.