THE disability sector breathed a sigh of relief when news broke in late March that President Benigno Simeon Aquino III had finally signed into law the bill exempting persons with disabilities (PWDs) from the value-added tax (VAT).

For advocates, the enactment of Republic Act 10754 had been one nerve-wracking wait.

Congress had already passed the bill in December, and the bicameral committee was expecting it to be signed before Christmas.

Christmas came and went, but there was still no law.

Then in January, Aquino, citing dire financial consequences, vetoed a bill seeking to increase the Social Security System (SSS) monthly pension of private retirees.

This stoked fears that the VAT exemption law might suffer the same fate, especially after the Department of Finance said the government stood to lose P4 billion if PWDs were exempted from paying VAT.

The authors of the bill, Juan Edgardo “Sonny” Angara in the Senate and Leyte 1st District’s Martin Romualdez in the House of Representatives, then started publicly urging the president to sign the bill. The Autism Society Philippines (ASP), a prominent disability organization, launched an online petition asking the president to sign the bill “with the sense of urgency it deserves.”

On March 23, Aquino finally approved RA 10754, capping a series of legislative and executive measures promoting PWD welfare during his administration.

Whether these measures — from economic opportunities to life-changing statutes — are in the long run consequential in making the right real for PWDs is another issue.

The sector is closely watching Aquino’s last three months in office, including the conduct of the May elections that are supposed to be accessible for PWDs under a law the president signed in 2013.

VAT exempt

RA 10754 will free PWDs of the 12 percent VAT, on top of the 20 percent discount they get for transportation fees; medical and laboratory charges; cost of medicines; admission fees in cinemas, leisure, and amusement places; and funeral and burial services.

Relatives caring for and living with PWDs will also be granted tax incentives.

The new law amends Republic Act 7277, the Magna Carta for PWDs. It is not the first Magna Carta amendment enacted during the term of the outgoing administration, though.

In April 2013, RA 10524 expanded a provision of the Magna Carta to reserve at least 1 percent of all positions in government for PWD employees.

Dated definition of disability

Disability advocates have lauded the amendments, yet continue to aspire for a much-needed, and seemingly basic, revision.

The Magna Carta still carries a dated definition of disability, which might have been acceptable when it was enacted in 1992 but is no longer the case today.

The law defines disability as an impairment, or a medical condition, even as international approaches to disability have shifted.

The Magna Carta also still uses the word “suffering” to define disability, said advocate Oscar Taleon, a retired Navy captain who became blind while in service.

“We would like that provisions (of the) Magna Carta will jive with that of the UNCRPD,” added Taleon, founder of the cross-disability organization Alyansa ng May Kapansanang Pinoy (AKAP-Pinoy).

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities requires state parties to promote and protect the human rights of PWDs.

The Philippines ratified the convention in 2008, but is “still not in full compliance” with it, said Carmen Zubiaga, acting executive director of the National Council on Disability Affairs (NCDA).

The UNCRPD defines disability as the result of “the interaction between persons with impairments and attitudinal and environmental barriers that hinders their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.”

The Magna Carta’s medical, as well as charity, approach is inconsistent with this definition.

“Since 1992 pa, wherein wala pa tayong idea ng (we still have no idea of the) rights-based approach to disability,” Zubiaga said.

Under the rights-based approach, she said PWDs are “entitled to the same rights just like any other citizen of this country.”

Economic opportunities

To be fair, the Aquino administration has produced a significant number of policies and measures for PWDs.

Zubiaga considers the inclusion of the disability agenda in the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) agenda as a major victory for the sector. (See PH worked for PWD inclusion in APEC declaration)

“Naipasok natin sa (We have included in) APEC yung (the) disability agenda, which will surely boost the participation of PWDs in the economy,” she said.

The declaration that capped the APEC Leaders Meeting in Manila in November mentioned PWDs thrice.

Leaders of the 21-member APEC encouraged collaboration with the disability sector “to find solutions to the challenges we face and build a better, more inclusive world.”

NCDA had started working for the inclusion of the disability agenda in the declaration two years before the meeting.

For Emer Rojas, who used to represent the PWDs to the National Anti-Poverty Commission (NAPC), Executive Order 417 is another measure expected to improve the economic opportunities of PWDs. (See Seize economic opportunities provided by law, PWDs told)

The EO requires government bodies to procure 10 percent of their goods and services from PWD cooperatives and organizations.

It only took effect in March 2014, during the Aquino presidency, despite having been signed in March 2005 because of delays in the crafting of its implementing rules and regulations.

‘Life-changing statutes’

For ASP, the equal opportunity amendment of the Magna Carta and the enactment in September 2013 of RA 10627, the Anti-Bullying Law, are two significant legacies of the Aquino administration.

These laws are “two life-changing statutes for many Filipino families who live with autism,” the organization said.

On the other hand, Ronnel Del Rio, a disability advocate working for the Batangas provincial government, said the enactment of key amendments in the Intellectual Property Code proves beneficial for a segment of the PWD sector.

“Dati-rati kasi, hirap na hirap ang mga bulag na makakuha ng audio materials, makagawa ng Braille materials kasi nga gawa sa copyright law (It used to be difficult for blind persons to use audio or make Braille materials because of the copyright law),” Del Rio said.

RA 10372, signed in February 2013, allows the reproduction of copyrighted works in specialized formats for noncommercial use by persons with visual disabilities.

Accessible elections this May?

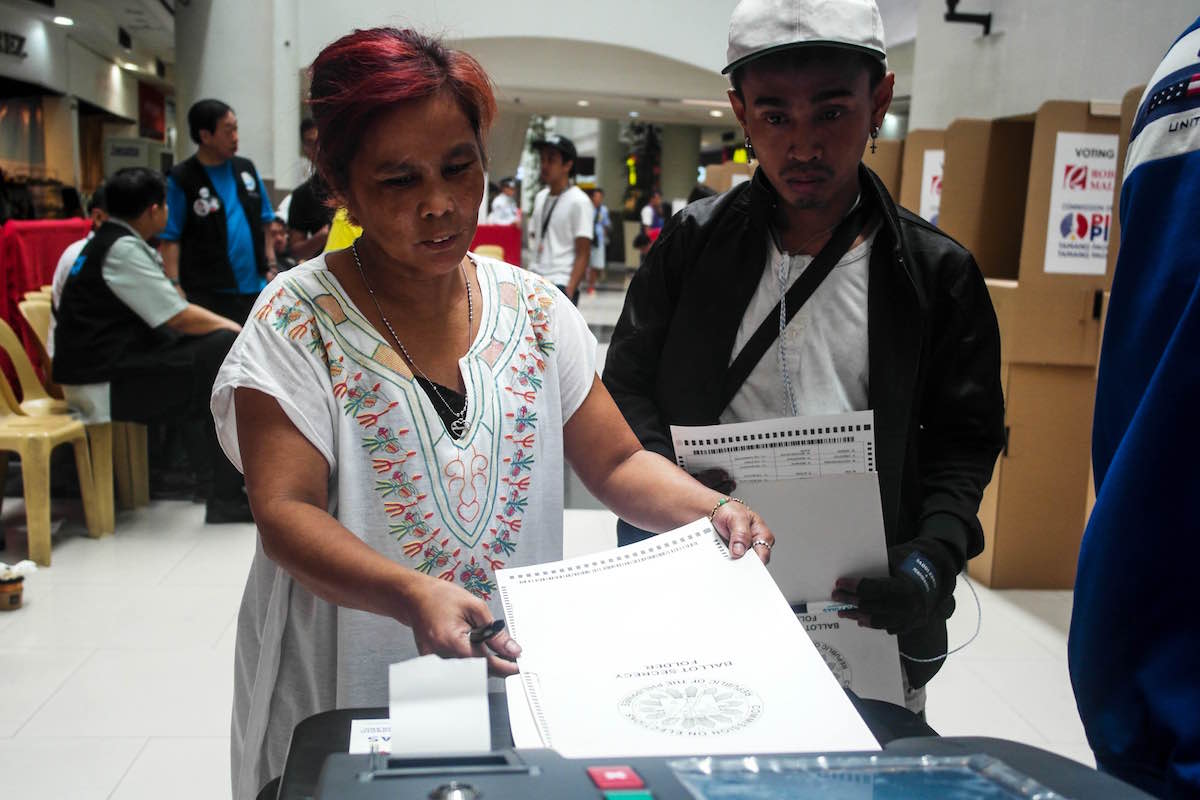

It was also in February 2013 that Aquino signed RA 10366 mandating the Commission on Elections (Comelec) to establish accessible polling places (APPs) for PWDs.

But the law would have little effect on the two elections held in 2013.

During the midterm elections in May that year, only two out of the country’s more than 36,000 polling centers were designated as APPs in what Comelec said was a pilot effort. (See Only 2 dedicated polling places for PWDs)

Nonetheless, the right to vote of PWDs was put on the spotlight, through increased media coverage, and by Aquino himself.

The president, in his fourth state of the nation address (SONA) just months after the elections, told the country how inspired he was by the story of Niño Aguirre, who had no hands and feet.

“Isipin po ninyo, hindi na nga makalakad dahil sa kapansanan, pilit pa rin niyang inakyat ang presintong nasa ikaapat na palapag ng gusali, para lang makaboto at makiambag sa tunay na pagbabago ng lipunan (Just think: Though unable to walk, he climbed all the way to his fourth-floor precinct, just so that he could vote and contribute to true social transformation),” Aquino said, thanking Aguirre.

By the time the barangay elections were held in October 2013, the implementing rules of and regulations of the APP law were out.

Came election day, however, the APP experiment, pilot tested in four select malls, failed: Only 10 voters with disabilities gave their consent to be transferred from their regular precincts. (See Only 10 PWDs to vote in special polling places)

The accessibility of voting places for PWDs remains an issue in the upcoming presidential elections.

The Comelec leadership has consistently expressed its commitment to making elections convenient for vulnerable voters, a category that includes PWDs.

It has conducted voter registration in malls, and is set to transfer polling places in select malls nationwide, targeting around 2 million vulnerable voters.

A month before the elections, signs of underachievement are already showing.

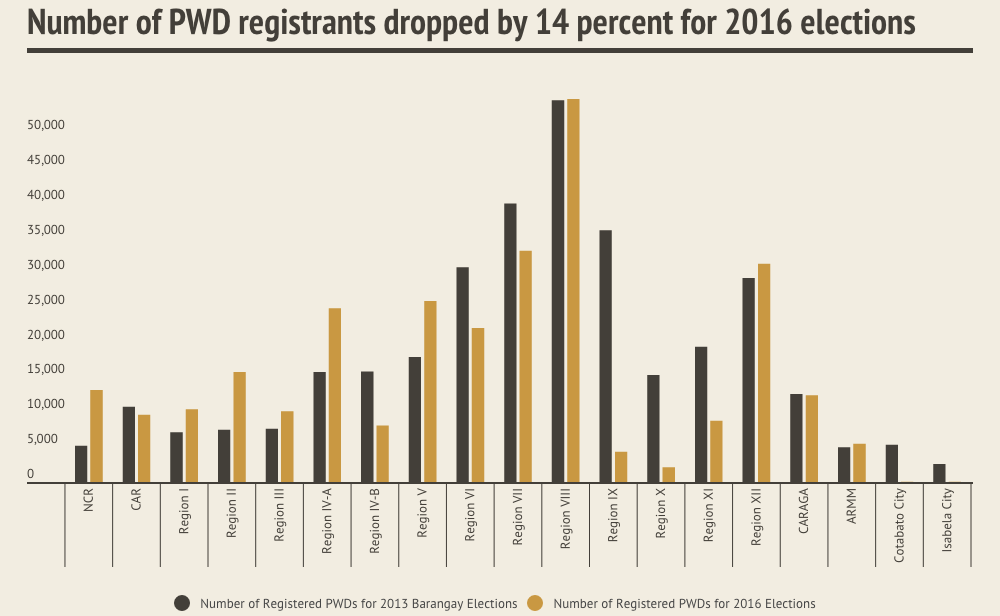

The number of registered voters with disabilities is down 14 percent from the 2013 polls despite efforts by both Comelec and civil society organizations to get eligible PWDs to register and vote. (See Fewer registered PWD voters for 2016 elections)

Explanations range from voters choosing not to declare their disabilities to disenfranchisement because of Comelec’s strict biometrics requirement policy.

Need for reliable data

This issue of PWD numbers runs deeper than just in the elections.

Insufficient and unreliable government data on disability is one of the unflattering legacies the Aquino administration would be leaving for the next president to take on.

When they take office in June, the next leaders of the country will not have the total count of Filipino PWDs to serve as basis for development programs.

This is because the census of population under Aquino in 2015 did not contain questions on disability. (See Census leaves out PWDs, angers disability council)

The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) said questions on disability would be included in the 2020 census. It also said it will conduct a disability survey this year.

A survey gathers data from a sample of the population, a census on all persons.

Absent updated statistics, policy makers would have to rely on the 2010 census results, which put the number of PWDs at 1.4 million, or 1.57 percent of the total population.

Not only are the figures old, they are far from the global disability prevalence estimated by the World Health Organization (WHO) at 15 percent of the world’s population.

Taleon offers one explanation for the discrepancy, which ties back to the dated definition of disability of the Magna Carta.

“Dito sa atin (Here in the Philippines), we look at more impairment,” he said, while other countries look at what he called “functionality.”

“Kung ang isang tao ay hindi makaakyat sa hagdan (When someone cannot climb a flight of stairs), he’s already considered (to have a disability),” Taleon said.

Numbers matter, and the government itself has said so.

Census data aims “to provide government executives, policy and decision makers, and planners with population data, especially updated population counts of all barangays in the country, on which to base their social and economic development plans, policies, and programs,” according to the PSA.

Taleon puts it differently: “Yung mga politicians, they will not mind a sector that has not a substantial number of votes. So dapat talaga malaman natin (we really need to know) how many are persons with disabilities.”