Last Nov. 15 in Bago City, Negros Occidental province, a motorcyclist was hit from behind by another rider, hurling him to the other side of the road where he was run over and killed by a speeding truck.

Less than a month before that, a speeding car hit a tricycle coming from the opposite direction, killing the driver and one of the four passengers of the utility vehicle in Tayabas, Quezon province.

One day in August, a speeding car at the Cavite Expressway crashed into a light truck, injuring five adults and a toddler.

The three cases had a common denominator – speeding vehicles.

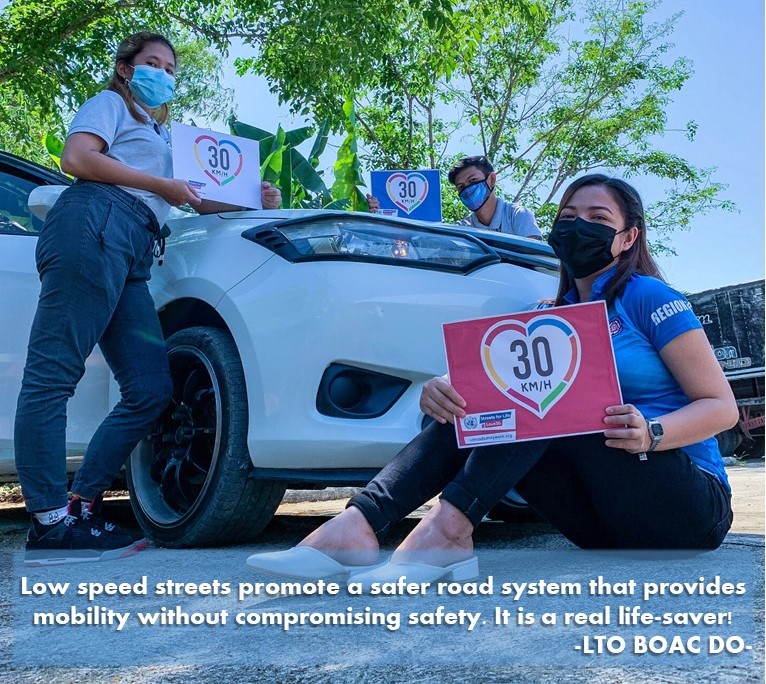

Photo from the World Health Organization Western Pacific Regional Office (WHO – WPRO)

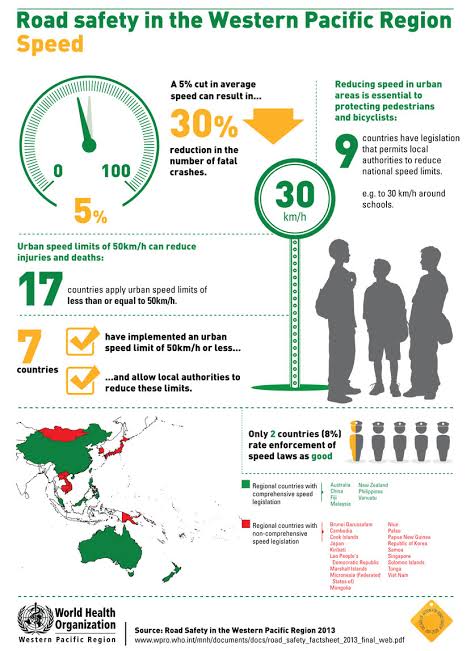

Speed directly influences the risk of a car crash, the severity of the riders’ injuries, and chances of dying, according to the World Health Organization. Enforcing speed limits are effective interventions to prevent death and serious injury, it said.

Speeding is the biggest contributor to road fatalities in the Philippines, officials say, but they also acknowledge that speed limit enforcement in the country is poor.

The three cases of speeding that took place over a period of three months had another thing in common. Upon investigation, it was found that the incidents occurred in areas without speed limit ordinances.

LGU-set speed limits

In January 2018, the Department of Transportation (DOTr), Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) and the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG) signed a Joint Memorandum Circular (JMC 2018-001) setting guidelines and standards for the classification of roads and setting of speed limits in different municipalities.

Joint Memorandum Circular (JMC 2018-001) setting guidelines and standards for the classification of roads and setting of speed limits in different municipalities

The JMC said there is a compelling need for local government units (LGUs) to issue speed limit ordinances to curb the rising number of road crashes around the country.

There are about 1,600 local government units all over the country and “probably 95 per cent of these do not have comprehensive speed limit ordinances,” says lawyer Sophia San Luis, executive director of ImagineLaw, a public interest law organization helping the government implement the JMC on speed limits.

A comprehensive ordinance refers to an appropriate designation of a certain speed depending on the condition of the municipality’s roads.

Speeding is a violation filed under reckless driving, according to Atty. Roberto Valera, field enforcement officer of the LTO. “It can be a ground for a citation. Reckless driving means endangering lives or properties.”

Data from the Philippine National Police Highway Patrol Group (HPG) show that 8,809 reckless driving incidents occurred from January to September 2019.

Nation-wide speed limits are set under the decades-old Land Transportation and Traffic Code, or RA 4136. Under the law and based on road classifications, the speed limit for cars on open roads is 80 kms per hour, but once the vehicle passes a crowded street, a school zone and when approaching intersections, the speed should dip to 20 kph. For trucks and buses, the maximum allowable speed on open roads is 50 kph.

Under the January 2018 JMC, however, LGUs are allowed to lower speed limits on roads within their jurisdiction and enact ordinances to implement these.

San Luis, together with DOTr Undersecretary Mark de Leon and LTO Assistant Secretary Edgar Galvante, signed last July 25 a memorandum of understanding (MoU) aimed at facilitating the nationwide implementation of speed limits through training.

The JMC had been in place for 18 months but its implementation has been hampered by the LGUs’ lack of skilled manpower in drafting speed ordinances and enforcing them.

Few LGUs are compliant

“So far, we have 15 (LGUs) that are compliant with the (JMC 2018-001). The rest cover only a few roads,” said San Luis, whose public interest non-profit has been the government’s partner in crafting and implementing the JMC.

Over 200 LGUs have ordinances that are “either ineffective as they do not classify roads in accordance with RA 4136 (the Land Transportation Code), or incomplete, as they only cover a few roads,” according to a report from the transportation department.

San Luis, meanwhile, says Region V and Region IV-A are among the areas that have submitted their reports on how many LGUs have speed limits within their provinces. “We’re analyzing that now if they comply with their JMC. We’re waiting for the other regions to submit their reports.”

When it comes to implementing comprehensive speed limit ordinances, not all municipalities that have enacted this ordinance are first-class municipalities or highly urbanized areas.

“Surprisingly, these are different types of municipalities. It’s a good sampling,” said San Luis.

An example is the municipality of Dipaculao, Aurora, which issued the ordinance without the engagement of ImagineLaw.

“They just heard it from, probably the media, that there is such a thing as the JMC and they used the template of the JMC to enact their ordinance,” San Luis added.

ImagineLaw offers assistance in training LTO enforcement officers, so LGU staff can go direct to their regional LTO office for training. “Ideally, after this whole project, after we’ve trained all the LTO trainers, the LGUs wouldn’t have to go to ImagineLaw for assistance. They can just go to the LTO for assistance.”

On-going training

The LTO offices for regional V and IV-A will be tested on their enforcement training.

“We will observe if they are conducting the training correctly and we will tweak it so that it considers the local context,” said San Luis.

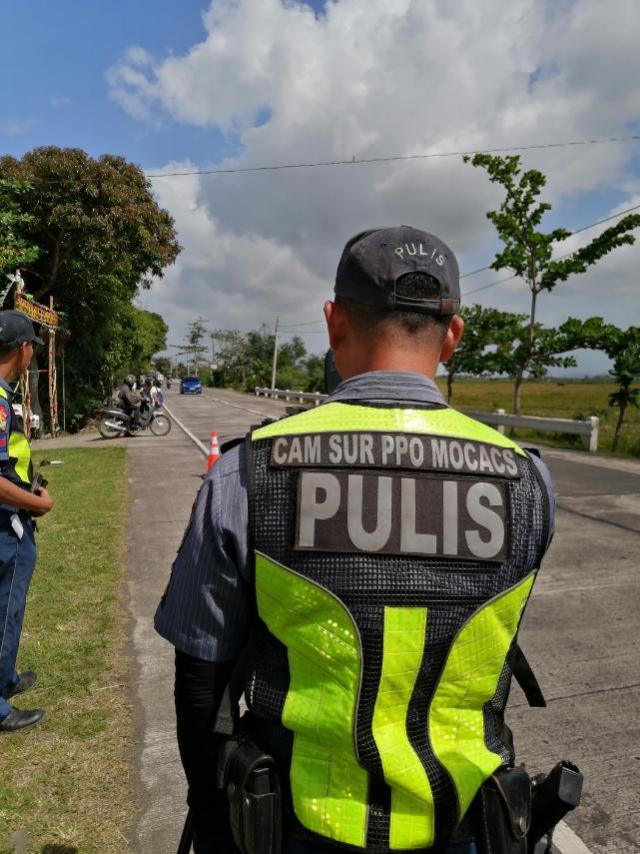

One such practical training took place in Camarines Sur last Nov. 30.

One of the enforcers from Camarines Sur Police Provincial Office (PPO) Motorcycle Cops Against Crime in the Streets (MOCACS) who underwent training. Photo from Sophia San Luis.

During the speed enforcement training with the LTO along Fuentabella Highway in Pablo Ocampo municipality, 30 vehicles were stopped by enforcers, according to San Luis. The drivers were apprehended for violating speed limits while enforcement officers were training in the use of laser speed guns.

In one vehicle, the driver was speeding and all passengers were not wearing seatbelts.

“As a training exercise, the LTO only issued warnings to the drivers,” she said. “Most of the drivers simply accepted the violation but appreciated that enforcement activities are being conducted.”

“This is why the regional trainings we are conducting with DOTr and the LTO have been crucial. Through these trainings we are able to reach hundreds of LGUs in a few days,” she added.

A National Speed Enforcement Plan, in partnership with the LTO, would be developed once all LGUs enact their respective ordinances, though there is no deadline for LGUs to do so.

While there are also no consequences under the law and the JMC, San Luis “hopes to get DILG to treat this with the same urgency as road clearing.”

“Of course not all of them enact, but at least we can say they have been made aware of their mandate,” she said.

Two months after ImagineLaw signed the MoU with the DOTr, it launched Dahan-dahan sa Daan, an online database on speed limits per municipality in the Philippines.

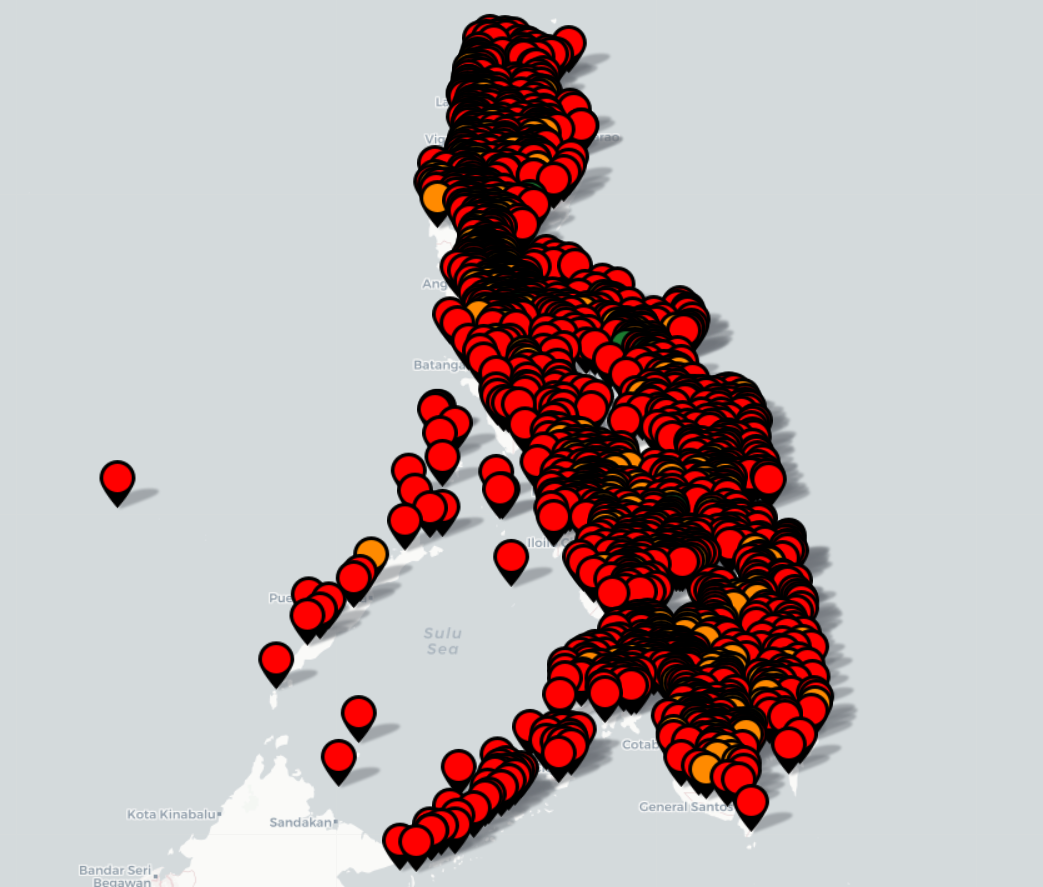

Philippine map with color-coded pins, most of which are red. Screenshot from Dahandahansadaan.ph

The site features color-coded pins per municipality. The colors green, yellow and red reflect the LGU’s speed limit ordinance. An LGU with a green pin means it has classified its roads and enacted a speed limit ordinance based on road conditions. Having a yellow pin means the LGU has speed limits but these are not based on their local road conditions and/or do not cover all roads.

Majority of the pins are in red. These are LGUs without speed limit ordinances.