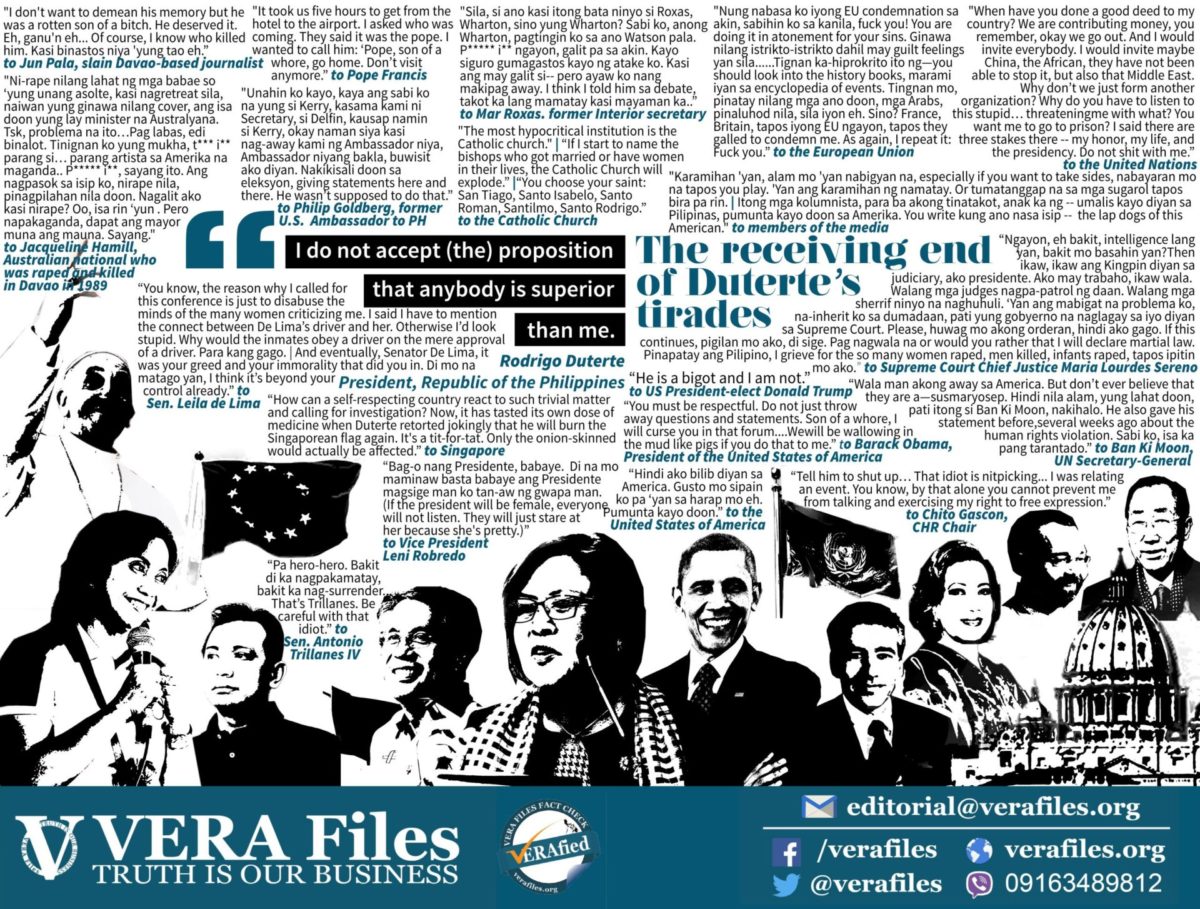

The exhibit “When Salvaged Logs Bloom,” which is being held at two sites (Stall 9, Cubao X, General Romulo Ave., Cubao, Quezon City and Green Gate Gallery, Lluch Park, Palao, Iligan City) until March 6, reflects the dual face of nature and humankind: destruction and creation. It is also in parts an indictment of the violent nature of the Duterte Presidency. This fading regime has spawned extra-judicial killings (EJKs) and red-tagging during its brutal war on drugs and insurgency.

Out of the deaths and the cries of the orphaned and widowed, the sisters Aba and Kiri Dalena, their mother, sculptor Julie Lluch, and floral installation artist and priest Jason Dy, SJ, have fashioned with their respective materials bold, life-affirming, hopeful statements.

Father Dy gave the title “When Salvaged Logs Bloom.” In the case of Lluch’s logs (debris or remnants from December 2011’s Typhoon Sendong), the meaning of “salvaged” was restored to the original—to be saved or redeemed. During Marcos’ martial law years, “salvage” acquired an opposite meaning—to be summarily or extra-judicially killed.

Father Dy of the Ateneo University’s fine arts department used flowers as materials for the installation because “their materiality conveys the dynamic processes of growth, blooming, decay and rebirth.” “As a priest, I relate this more to the theology of the paschal mystery—life, passion, death and resurrection,” he said.

He continued, “As an artist, I employ them as metaphors of the persistence of life amidst the threat of violence and death. Aesthetically, I’m informed by the Japanese aesthetics of wabi-sabi, a philosophical view on the beauty of impermanence, incompleteness and transience.”

In his artist’s statement, Father Dy, national chaplain of the Jesuit Volunteers Philippines, wrote: “Perhaps, like these natural processes, the war against illegal drugs, though intended to fight substance abuse, illegal trade, organized syndicate, exposed the hard facts of violence, injustice and brutality. Dried flowers arranged on each log connote wasted lives as collateral damage in the drug war. It could also be an offering of the families left behind seeking the elusive justice.”

He met Julie Lluch and her two daughters at various art events. He admires their socially relevant works and their creative practices. Together they have gotten involved in art projects that advocated for life and against violence, especially against EJKs.

When Kiri saw his large floral installation in memory of the EJK victims at the Jesuit Mission Station in Caloocan in December 2021, she invited him to propose a project at Stall 9 which is managed by the Respond and Break the Silence Against the Killings (RESBAK) team.

For the last six years, Father Dy and Kiri resisted the anti-illegal drug campaign of the government that has “terrorized entire communities, mostly the poor, and allowed for a culture of violence and the absence of the rule of law to flourish and be normalized. So these are common threads in our art and social practice that we found,” she said. Lluch and Aba have been just as vocal.

She said the plan was originally for a solo show by Father Dy in the last quarter of 2021. “We got wind of his creative, ritual interventions to commemorate the victims of the drug war in Caloocan, an area most affected by killings related to the government’s anti-illegal drug campaign beginning in 2016.”

Target opening was January this year, but the Omicron surge intervened. Lluch and her daughters were caught and trapped in Iligan. It was also their first time to return there after two years of COVID-19. (Lluch has roots in the city.)

Father Dy’s show was postponed. During an online meeting with him, the idea of a parallel exhibit in Iligan came up along with creating an art space in the Lluch home. Kiri said, “The broad ideas and themes of his exhibit ran parallel to what we were surrounded with in Iligan: the remnants of logs and other trees washed out during Sendong.”

In 2012, Kiri exhibited installations and videos in a powerful show, “Washed Out,” at Finale Art Gallery. Installed were huge logs of Sendong in their raw state. Lluch described the disaster as “a reminder of the environmental catastrophe that claimed over a thousand lives in Iligan City. The illegal logging issue then was hardly addressed by government as if the catastrophic flood was all the fault of God or Nature.”

Lluch described what she saw when she went home to a post-Sendong city: “Thousands of forest debris littered the shores of Iligan all the way to Misamis Oriental. Hauling the logs and trees from the sea and sand was a gargantuan task. Once assembled in the site, my sister Almita and I hired a forester to identify the trees. Apitong, tanguile, nilo, molave, kamagong are some names that I remember.”

The sisters bought jigsaws, grinders and “a real cool chainsaw, small and handy enough for ladies to use.” Together with Barangay Captain Robert “ Dodong” Fuentes, whose hobby was carpentry, they held a three-person show in Iligan 10 years ago using debris and logs from the typhoon. Fuentes and his brother Ronald were later included in the notorious Drug Watch Lists after Duterte came to power. In 2017, the brothers were both killed by unidentified assailants eight months apart.

At the simultaneous artists’ reception in Cubao and Iligan held Feb. 26, mothers took turns reading names from a partial list of EJK victims in an area of Metro Manila (Caloocan, Navotas and Malabon), a contemporary twist on the traditional pabasa, while candles burned and Father Dy’s flowers stood by them.

Lluch said their shows might seem “out of step with the present election campaign fever, but anytime is a good time to stir community responses to the issues of environment and human rights.”

She added, “Flowers, like candles and prayers, are a natural part of the ritual of honoring the dead. Father used the word ‘bloom.’ Immediately, flowers became part of the show. He uses flowers of many kinds and colors as the medium of his wonderful installations. Remembering and memorializing is made more poignant and beautiful when expressed with flowers whose ephemerality and brevity is like a man’s life.”

In her artist’s statement, she asked, “Who really killed the people? Who shot the innocent in cold blood, speeding away in a motorcycle tandem?” For an answer, she stated, “The same avaricious men who rape the forests and women, drunk with power and impunity! Should we blame the fallen trees? Should we wage war against the hapless people, the poor especially? Trees are our friends. We cannot survive apart from them. Nature can do without us, are better off without men. We do not kill trees. We honor the sanctity of life.”

Aba, who calls herself a “progressive Christian,” contributes her “Liquid Love” series. The works look drenched in blood which isn’t accidental for the artist associates blood with the blood of Christ the redeemer.

She relates the color red also to the “country’s pressing political realities, foremost of which are the EJKs,” according to Betty Uy-Regala in the artist’s statement. At the Iligan reception last Saturday, Aba was emotional as she paid tribute to volunteer lumad teacher Chad Booc whom she personally knew and who was killed by the military on suspicion of being a New People’s Army member. She rhetorically asked if she was in the hit list next with her own part-time stints as teacher for lumad children.

“When Salvaged Logs Bloom” also includes screenings of short films by Adjani Arumpac (“Count”), Jef Carnay (“o horror horror horror”), Shireen Seno (“To Pick a Flower”), Aba (“Krus at Bayan Ko”) and Kiri (“Alunsina”).

Following is Kiri speaking in her own words about Sendong, its impact on the family, the repercussions of the EJKs and their own involvement as resisters:

“The last work and series of stories that I am sharing is connected to my mother’s birthplace here in Northern Mindanao where a visit of only a few days has been prolonged because of a COVID surge in the capital.

“The windows, stairs and doors of the house where I am staying are built from a narra tree, planted by my grandfather decades ago, that was felled by Sendong, a strong storm that hit the region in 2011.

“The damage to our family’s property is small compared to the damage left by the thousands of logs and trees that were washed down the mountains, destroying bridges and entire communities that lay in its path.

“In drawings made by children, they drew the trees that they climbed as the water from a nearby river began to rise and the logs and uprooted trees that they eventually rode to save themselves. One of these children rode a tree down the river and was rescued from the open sea a day after. She travelled on top of the uprooted tree for as far as 43 kilometers. Months later, in the process of making a short film, the young girl revealed why there are snakes in her drawings. She whispers to her brother that a Philippine cobra was clinging for dear life on the uprooted tree that she swam to and rode after the floodwaters washed away their home. Like her, the snake was just trying to survive.

“Many months later, my mother asked permission from the barangay captain of the community for the remnants of these trees that were not used for rebuilding homes. Most of the uprooted trees left untouched were from the balite or banyan species which people feared because of the belief that spirits resided in them. My mother cleaned these remnants and preserved them in her garden. Seeing what my mother did, the barangay captain also began collecting the debris and built installations in their community. My mother, her sister and he put these works together and invited people to come. They tried to identify each tree species from their remains as they went around.

“That was in 2012. Four years later, after Duterte came into power and a former police chief was installed as the new town mayor, the barangay captain was included in the watch list, a feared component of the government’s drug war which collects the names of so-called drug personalities in the communities. In 2017, he was shot dead by unidentified assailants. Fearing for their safety, the surviving members of his family decided to forego seeking an investigation.

“I share this story because I recently suggested reframing the story of the remains of the logs found in our home to include the narrative of the drug war killings. We are far away, but we consider this a form of solidarity to the work that other artists, journalists and activists have been doing to carry on the stories of the victims of the drug war, whether they are in Manila or in Iligan City.”