Calling it an “ancestral home,” San Juan City mayor Francis Zamora announced on Twitter on July 5, 2021, that the house of the Marcoses in their city will be part of a “historical trail” that they “will be launching this year to help promote San Juan as a tourist destination.” This he tweeted while at a dinner at the said house to celebrate Imelda Marcos’s 92nd birthday.

On November 26, 2020, Mayor Zamora previewed in a Facebook post what he calls the San Juan historical bike trail that includes the “Marcos Mansion.”

San Juan Mayor Francis Zamora and wife, Keri, with former First Lady Imelda Marcos, Sen. Imee Marcos and former Sen. Ferdinand “Bongbong”Marcos, Jr. at theMarcos house on Ortega street.

Imelda and Ferdinand’s house in San Juan may indeed be something for the tourists to gawk at. And surely it will pique their interest if they will learn more about what went before in this storied abode.

To begin with, there was the “first” Mrs. Marcos who lived there before Imelda.

“There was Carmen Ortega,” Primitivo Mijares wrote in The Conjugal Dictatorship (1976), “with whom the president had four children, two of them before he became senator of the Philippines.”

Not much is known about Carmen Ortega or her children by Marcos. Biographers of both Ferdinand and Imelda were even unsure how many children there really were.

What was known then was that Carmen was Miss Press Photography 1949. Mijares described her as “a beautiful Ilocano mestiza.” Her engagement to Ferdinand was announced in the Manila dailies in August 1953. She had been living with Ferdinand about a couple of years by then in the house on Ortega Street (now Mariano Marcos; named after Ferdinand’s father who was executed by guerilla forces in Northern Luzon for alleged treason in 1945).

In Imelda (1988), Beatriz Romualdez Francia, Imelda’s niece, recounted what Loreto Ramos, a cousin of Imelda, remembered about Carmen and Ferdinand. Loreto “saw Ferdinand and Carmen Ortega together once and she remembered Carmen for her good looks and rosy cheeks. Loreto ran into the pair at the office of Atty. Quilates at the Central Bank in ‘52. They made an impression on her and Loreto remembers vividly that Ferdinand had his arm around Carmen . . . He introduced Carmen to Atty. Quilates as ‘Mrs. Marcos’.”

When Imelda and Ferdinand got married on May 1, 1954, with Imelda unaware of Ferdinand’s first family, Carmen Ortega and her children were moved out of the San Juan house. According to Mijares, “Carmen has been amply provided for, along with her brood of four small Marcoses.”

When Imelda learned of Carmen Ortega and her children by Ferdinand, Mijares recalled that she demanded that they “be ‘thrown away, some way far from my sight.’

Ferdinand’s mother, Josefa, with the help of some of Ferdinand’s trusted lieutenants, made sure that Carmen Ortega remained out of Imelda’s way.

Later on, Marcos propagandists would outright lie to erase Carmen and her children from Ferdinand and Imelda’s love story. But whatever stories they have spun, Imelda cannot unlearn what she knew.

Carmen’s prior presence in the San Juan house may have further rankled Imelda when Ferdinand barred her from making any changes in how the house was put together. Some credit it to Ferdinand’s superstition. He found the house lucky as it was.

However, Imelda’s anger over Carmen Ortega did not lead her to walk out of the marriage. Instead, she tried to find ways to keep her husband for good. Citing again Loreto Ramos, Francia wrote that Imelda “once confided to her [Ramos] about her discovery regarding Ferdinand’s common-law wife, Carmen, and his children by her. Imelda said she made a pilgrimage to the shrine of Our Lady of Fatima in [Portugal] and prayed that she be quickly blessed with a child by Ferdinand to keep him from roving.”

Ferdinand’s relationship with Carmen Ortega was just one of the secrets that Imelda had to bear in the Ortega house. As a politician’s wife, Imelda not only had to learn the ropes of how to deal with the parade of supplicants asking for various favors at all hours of the day from Ferdinand (then three-term congressman of Ilocos Norte). She would also eventually learn the cost of the favors that Ferdinand traded in.

Their fabled eleven-day whirlwind courtship—more of “an amorous bulldozing” for James Hamilton-Paterson in America’s Boy (1999)—did not prepare Imelda for her husband’s persistent plotting to further his political career. An effort that drove Imelda to the point of a mental breakdown two years into their marriage.

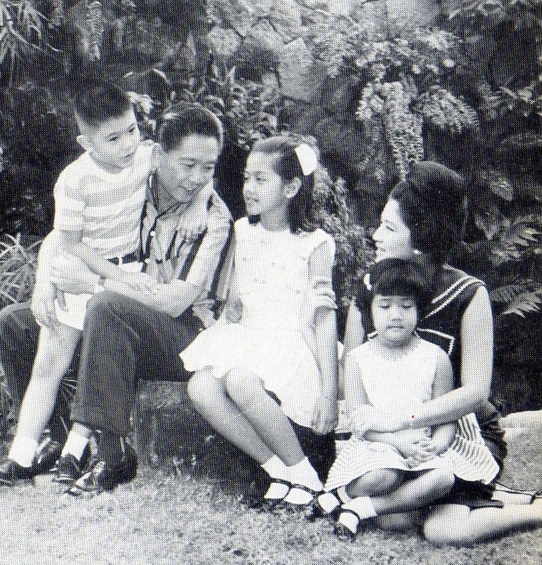

Marcoses at Ortega before they moved to Malacañang in 1965. Source: Kerima Polotan, Imelda Romualdez Marcos: A Biography. New York and Cleveland: The World Publishing Company, 1969.

Francia portrayed Imelda as being trapped. “She could have no peace in her house. Ortega was so packed with callers that at times she could entertain her own friends only in her bedroom. Moreover, Ferdinand, who had hounded her so, was now emphatic about wanting her to change into a sophisticated urbanite. It was quite a crash course Imelda had undertaken. She was being obliged to change drastically from her old Tacloban self.”

And this from a man who betrayed her right at the start of their marriage. The whole house was proof of that deceit.

For Hamilton-Paterson, Imelda’s effort to step up, “far from restoring her branch of the family to public esteem, looked like guaranteeing its enduring status as faintly pariah.” And all this because of her husband. “For all his wealth and growing power, he was revealed as indelibly provincial, the exemplar of rough-and-ready Ilocano politics of the variety she must have heard a lifetime of Romualdezes openly disdaining,” he wrote.

Yet Imelda, on her own, managed to set aside the disdain of others. To cure her afflictions, the doctors advised Imelda to practice auto-suggestion. In Kerima Polotan’s 1969 biography of Imelda, Imelda just had an epiphany one day. “Suggestion had become fact. She told herself she was lucky, and she was—she had the love of a good husband, the affection of fine children, youth, beauty, comfort, friends, and the saving perception to regard all these as opportunities to help others as well as Ferdinand.”

“Having accepted the terms of her kind of life,” Polotan continued, “she never again flinched or took a step backward . . . The headaches stopped forever, the vague pains disappeared, and the double vision fused to become a single, concentrated look on the possible heights her husband’s career might take.”

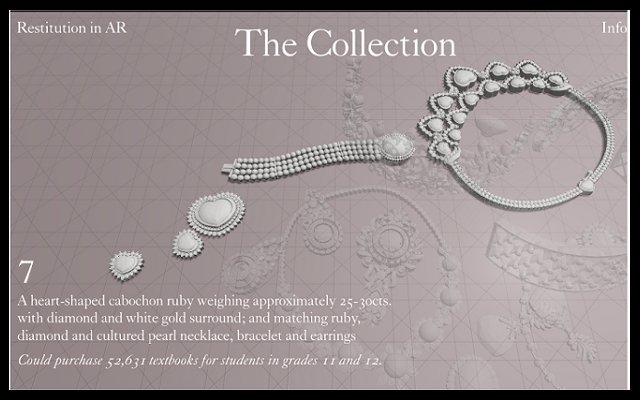

But, of course, the wealth Ferdinand threw her way, helped Imelda find joy. As recounted by Francia, her mother once visited Imelda and in the course of the visit “Imelda spread out her jewelry for her viewing. Auntie Meldy said, ‘You see, Amy, whenever I’m depressed, I spread my jewelry out on my bed; it cheers me up quickly’.”

Imelda’s mania for jewelry-induced happiness will soon plunder a nation’s wealth. But that will come later. Until then, there was no better vantage point from which to survey her and Ferdinand’s imminent future than from 204 Ortega Street. From there, their next stop would be Malacañang. And as revealed by Frederick King Poole and Max Vanzi in Revolution in the Philippines (1984), in that house not only did Imelda practice how to be first lady, she also imagined how to be queen.

“Back in 1965, on the night Marcos won the election that made him President, Presy Lopez, later Psinakis, was present at their home. She came upon Imelda in front of a mirror. The new First Lady was watching herself make stiff motions of greeting with her right arm. ‘How does she do it?’ Imelda wanted to know. ‘How does the Queen of England wave?’”

Ferdinand buys a house

“His sprawling bungalow with its magnificent gardens in smart suburban San Juan on Ortega Street was a showcase of his success.” That was how Carmen Navarro Pedrosa, in The Rise and Fall of Imelda Marcos (1987), regarded Marcos’s place in San Juan.

But not before qualifying the roots of such success. “Marcos’s reputation in knowledgeable political circles was that of a hustler. Although he carefully nurtured a scholarly and statesmanlike image, it was no secret that he sponsored avaricious Chinese businessmen in Congress, and he was known there as a wheeler-dealer. Moreover, as a representative of the Solid North, where money and violence ruled, his capacity for ruthlessness was well-known.”

A bit of hustling does appear to have attended the way Ferdinand bought his home in San Juan.

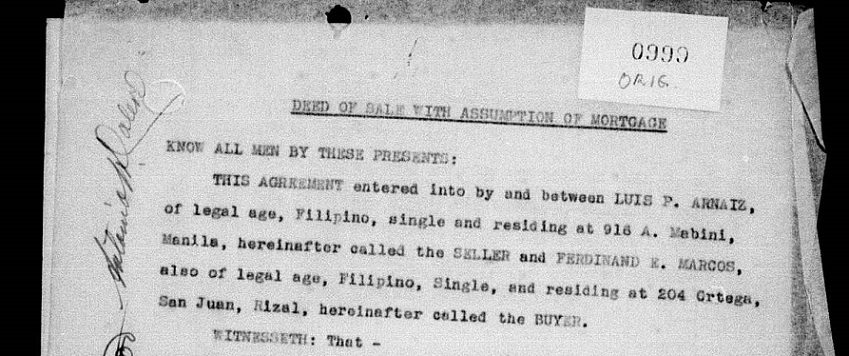

Portion of the Deed of Sale of 204 Ortega to Ferdinand Marcos, August 1951 (from digitized PCGG files)

Based on documents seized from Malacañang after the 1986 EDSA Revolution, Ferdinand bought the spacious bungalow and the sprawling lot in San Juan on August 14, 1951 from a Luis P. Arnaiz. Covered by two titles, the almost 1,600 sq. m. property cost the thirty-three year-old lawyer and lawmaker PHP 50,000.00 (about PHP 12.5 million today). According to a memorandum listing his income, assets, and liabilities as of 1951 which was given to the Bureau of Internal Revenue to contest a claim made in 1953 that he owed the state nearly PHP 100,000.00 in taxes and penalties, Marcos was able to buy the San Juan property—as well as a house and farmland in Batac, Ilocos Norte, for about PHP 20,000.00 and PHP 2,000.00, respectively—through a number of loans in addition to his earnings. His stated income for 1951 was PHP 71,800.00—nearly nine times more than his stated income in 1949, the year he first became an elected official.

In a transcript of a statement taken from then Congressman Ferdinand Marcos in 1955, the future president said, “In 1950, I began negotiating for the purchase of my present residence in San Juan, including [the] lot. I had so many rivals then on this property, hence, in anticipation of an eventual agreement with the owner on the matter, I had to borrow money in order that I would have ready funds.” Specifically, he borrowed PHP 35,000.00 from Pablo Floro and PHP 15,000.00 from Alfredo Montelibano. The funds were given to him in cash, and he kept them in an heirloom safe at home instead of depositing them in a bank. Apparently the loans were not secured; “My friends trust me,” said Marcos.

The deal to buy the property was not completed in 1950, however, so, according to Marcos, he used the PHP 50,000 “for other purposes.” The following year, Marcos contracted a further PHP 46,000.00 in liabilities: a chattel mortgage loan of PHP 33,000.00, as well as a PHP 13,000.00 debt to the Philippine Trust Company, which was the balance of a mortgage loan taken out by Arnaiz against the San Juan property that Marcos had assumed. By December 31, 1951, as per his own declaration, his total indebtedness amounted to almost PHP 130,000.00.

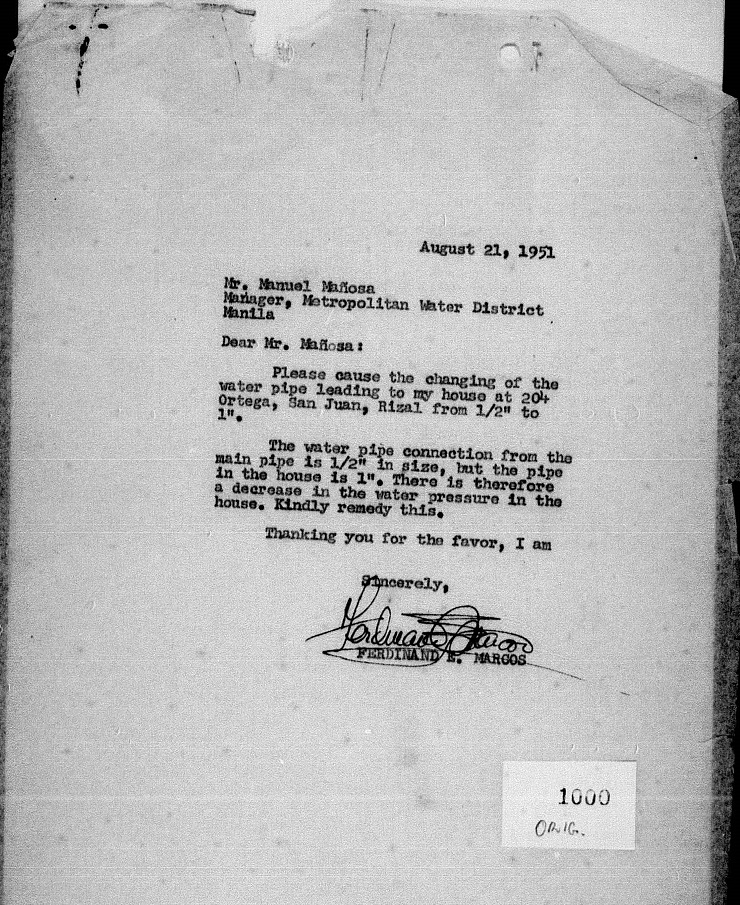

Copy of a letter from Ferdinand Marcos to the manager of the Manila Metropolitan Water District right after buying his house in San Juan (from digitized PCGG files)

Imelda makes a home

According to Ferdinand’s profile in the 1967 Philippine Officials Review, “Imelda Romualdez, a great beauty from the well-known Romualdez family in the province of Leyte, brought to 204 Ortega Street, San Juan, Rizal on May 1, 1954, Youth, Grace, Happiness, and many years later, offered her husband the laughter of three well-disciplined children—Imee, Bongbong and Irene.”

According to Hartzell Spence, in Ferdinand’s 1964 biography, For Every Tear a Victory, a month after moving in, she joined her husband on a “long honeymoon” that took them from Hong Kong to North America—intercut by Ferdinand’s official functions abroad. They were back on Ortega Street by early 1955 at the latest.

Soon after settling back into their San Juan home, Imelda became pregnant with her firstborn, Imee. Pedrosa, among others, state that 204 Ortega also started to regularly feature Imelda’s brothers and sisters, whom Ferdinand treated like his own siblings. Imelda also brought her father, Vicente Orestes, to her house in an attempt to save his life from late-stage cancer. However, soon after arriving in Manila, in September 1955, Vicente died at his daughter’s house, where his wake was then held.

Besides housing a growing (extended) family, 204 Ortega was also a commercial address. Among the files taken from Malacañang after EDSA are income tax returns for a Lammin Mining Company, office address at 204 Ortega, with Imelda Romualdez-Marcos listed as president. None of the ITRs from 1958 to 1961 show that the company had any income. Other documents show that Imelda found herself holding shares of stock (e.g., in the Steel Tubing and Rolling Mills Company) after contracting marriage.

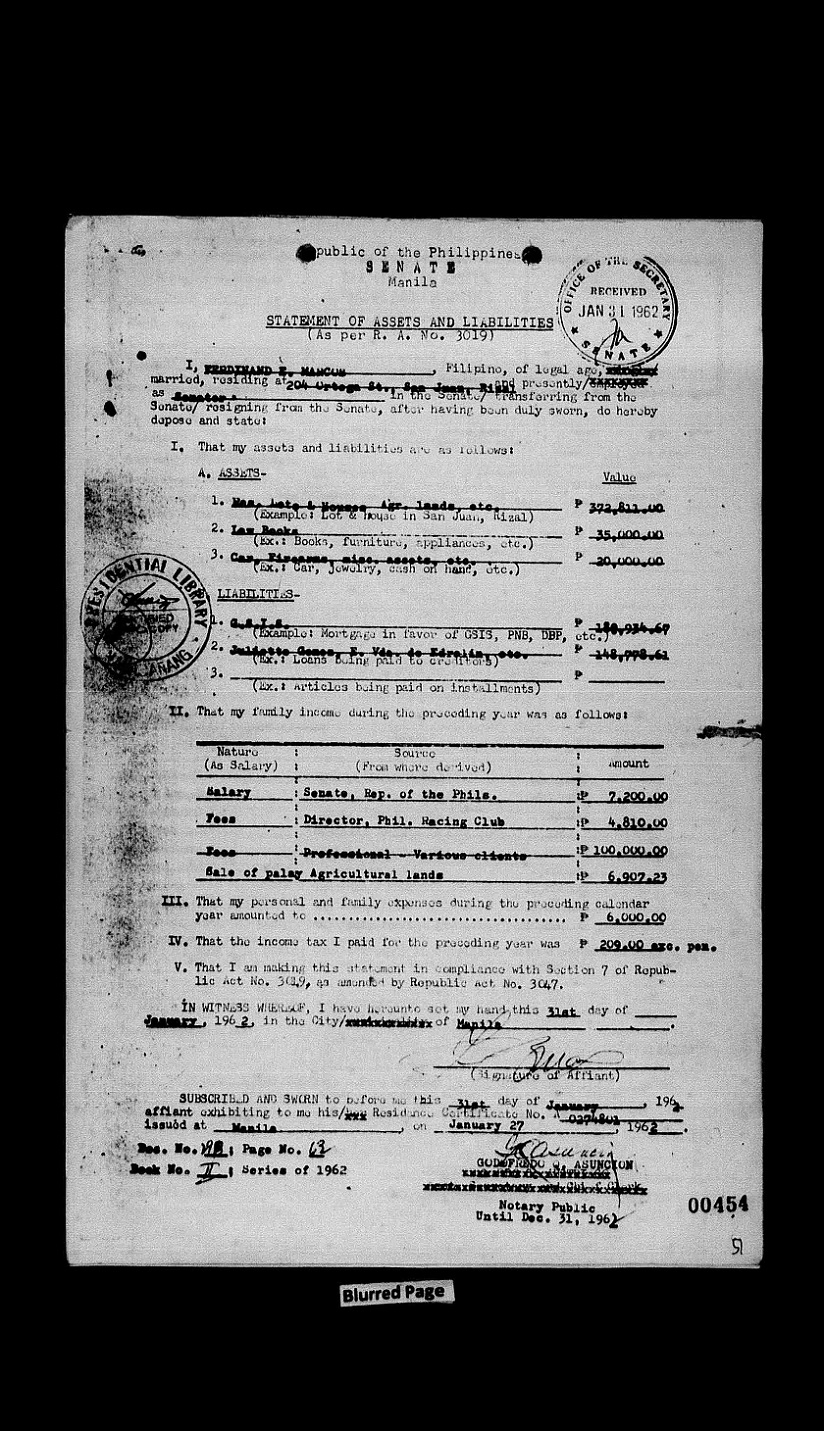

Even with their real properties and their stocks, they were not millionaires, based on Ferdinand’s official declarations. According to his Statement of Assets and Liabilities filed on January 31, 1962, his income at that time totaled PHP 118,917.23—PHP 7,200.00 of which came from his salary as senator, and PHP 100,000.00 from legal fees. But he also had notable liabilities, including a considerable loan from the Government Service Insurance System. Based on his SAL, his net worth at the start of 1962 was less than PHP 100,000.00.

Campaign/Drop-off headquarters

The Ortega house was Ferdinand’s national campaign headquarters. It often continues to function as such for his heirs to this day. It was where campaign strategies were discussed and political connections were strengthened. According to Pedrosa soon after they were married, “[describing] the house to his new bride, [Ferdinand] said, ‘It is made for entertaining.’” Indeed, those writing about how the house was in the 1950s and the 1960s note how unceasingly busy it was, with people—and money—coming in and out of it at all hours.

Spence noted that after becoming Mrs. Marcos, Imelda took upon herself “the burden of 4,000 ritual kinships”—kumpadres and kumadres, which necessarily meant inaanaks—that were mostly “acquired by her husband politically.” Spence stated that Senator Marcos’s wife oversaw a household that saw 150 visitors a day, which supposedly meant the daily preparation of “60 breakfasts, 250 lunches, and 30 dinners.” Imelda’s stay-in staff numbered 16, a little under half of the household staff she commanded. If this is true, then the expense for maintaining these connections and entertaining callers would have been immense.

As much as Ferdinand was spending, however, he was apparently also accumulating a presidential campaign war chest. According to Rafael Salas, head of Marcos’s 1965 presidential campaign, in his biography written by Nick Joaquin, while operating out of 204 Ortega, “Marcos came into the fight with money of his own. He had been preparing to run for President for years and had accumulated what I estimated to be some fifteen million pesos for the campaign.” If true, given his stated income vis-a-vis his expenditures and debts, it is puzzling how Ferdinand was able to accumulate PHP 15,000,000.00 from his publicly stated sources of revenue.

A strange and true answer was: Ferdinand and Imelda hid their loot under their bed. Imelda had no qualms showing the sacksful of money they had to close relatives. Six years into her marriage to Ferdinand, then a first-term senator, Imelda was able to say, “Money doesn’t mean much to me anymore.” And: “Our money comes in sacks. I’m tired of counting money.” Imelda made these remarks to her cousin, Loreto Ramos, Francia cited Ramos in her book.

Salas claimed that Ferdinand initially used his own (secret) money during the campaign because pledges did not immediately come through. However, “[as] the campaign drew to a climax, the businessmen started to smell a Marcos victory and began contributing generously to his campaign . . . so that he came out richer in the end.”

Indeed, according to then Supreme Court Justice Renato Corona, in Republic v. Sandiganbayan (July 15, 2003), Ferdinand only reported an income of PHP 16,408,442 from 1965 to 1984. Of that, PHP 11.1 million was supposedly income from Ferdinand’s legal practice, of which PHP 10.6 million were purportedly received only between 1967 to 1984, when he had already been barred from practicing his profession. Corona noted that Marcos never claimed that he had any receivables from any client in his 1965 ITR, and that his stated net worth by December 1965 was only PHP 120,000.00—more or less the same as his declared net worth in 1961-62. According to Corona, “[the] joint income tax returns of [Ferdinand] and Imelda cannot, therefore, conceal the skeletons of their kleptocracy.”

To Malacañang and back

Sometime after the Marcoses had already moved into Malacañang, the portion of Ortega Street fronting the Marcos house was renamed after Ferdinand’s father. Throughout their overextended stay in the presidential palace, the Marcoses did not forget to take care of their San Juan home. Among the files in the hands of the PCGG, one can find evidence of renovation costs for 204 Mariano Marcos amounting to almost PHP 200,000.00 in 1974.

Yet when Imelda returned to the Philippines in November 1991, with Ferdinand dead and their exile ended, she stayed at a hotel. A decision regarding an electoral case filed against her in 1995 said the house “was in a state of disrepair, having been previously looted by vandals.” She lived in various places in Makati for about a year, but in her certificate of candidacy for president in 1992, she stated that she was a resident of San Juan.

By that time, numerous properties of the Marcoses had been sequestered by the PCGG. According to an Associated Press article in the Manila Standard on May 22, 1992, the PCGG had repeatedly stated that the “house in Ortega, San Juan” had never been sequestered; it was one of the few assets Ferdinand clearly bought before he became engaged in presidential plunder. If it was looted—Arturo Aruiza, in Ferdinand Marcos: Malacañang to Makiki claimed that even the washbowls were taken—it was not by government order.

Statement of Assets and Liabilities as of January 1962 of then Senator Ferdinand E. Marcos (from digitized PCGG files)

A House of secrets and lies

While on hiatus from politics in 1998, Imelda let the late Christine Herrera of the Philippine Daily Inquirer into her homes for several weeks for a series of interviews. These were the main source for a series of articles in the Inquirer in December 1998. In the first article, Imelda was quoted as saying, “We practically own everything in the Philippines, from electricity, telecommunications, airline, banking, beer and tobacco, newspaper publishing, television stations, shipping, oil and mining, hotels and beach resorts, down to coconut milling, small farms, real estate and insurance.” She asserted that she would reclaim these from the Marcos cronies. The Marcoses have not yet succeeded in this effort.

Imelda told Herrera that her husband was able to acquire all that wealth through “secret gold trading.” She said that her husband had amassed 4,000 tons of gold, showing Herrera a “three-inch thick document” in support of her claim. Herrera noted that in “several interviews, the [Inquirer] found Ms. Marcos’ aides and lawyers busy sorting out papers from a room full of documents at the Marcos ancestral home in San Juan…to prepare the Marcos cases against the government and the cronies.”

This was likely the beginning of the “evidence room” in the San Juan house—actually Ferdinand’s former gym—where Imelda would take interviewers from local newscasters like Mel Tiangco to foreign documentary filmmakers like Lauren Greenfield (The Kingmaker). Featured there are the documents presented during her racketeering trial in New York.

Imelda is hardly shy when showing her documents, even though some of them, especially the purported gold certificates, have been found to be spurious. Then Bangko Sentral Governor Gabriel Singson, in an Inquirer article published in December 1998, described Imelda’s claims as “unbelievable.” Another BSP official noted that if what Imelda was saying was true, then the late president “violated the foreign exchange controls” by concealing his gold trading. In any case, Imelda “failed to show other documents proving that her husband was an active buyer and seller of gold.”

Still, Imelda’s doubtful documents have become a staple of recorded tours of 204 Mariano Marcos. Photographs and footage of such tours show that she also kept on display the fake Philippine Collegian cover showing Ferdinand’s fake bar exam results and portraits of Ferdinand and Imelda in regal garb.

While this shrine to Marcos glory has never been sequestered, the Marcoses have at least twice nearly lost the house to satisfy judgments against them. It appears, however, that to this day, the Marcoses retain ownership of their “ancestral house” in San Juan.

At the very least, the San Juan house has yielded fifteen paintings seized in 2014. In a December 2019 Sandiganbayan partial summary judgment, these and hundreds of other artworks worth USD 24.3 million in total—USD 24 million more than the incomes of Ferdinand and Imelda throughout the Marcos presidency—were declared ill-gotten.

That judgment was one of two recent issuances by the Sandiganbayan against the Marcoses. The other one is Imelda’s criminal conviction for seven counts of graft, for which she has posted bail and filed an appeal. It was promulgated on November 9, 2018. She was absent when the decision was read, purportedly because she was, per her counsel, indisposed. That night, at 204 Mariano Marcos, she was at her daughter Imee’s birthday party, which was attended by former presidents Gloria Macapagal Arroyo and Joseph Estrada, Solicitor General Jose Calida, and Davao City mayor Sara Duterte.

In sum, 204 Ortega, now Mariano Marcos, is truly historical. It is linked to a former flame of Ferdinand who has been all but erased from his official biographies. It is from here that Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos launched their plunderous conjugal dictatorship, time and time again proven by the courts. It plays a role in maintaining Marcos myths to this day. Are these to be mentioned in San Juan’s historical trail?

(Miguel Paolo P. Reyes and Joel F. Ariate Jr. are researchers at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. Larah Vinda Del Mundo provided research assistance. This piece is part of their on-going research program, the Marcos Regime Research.)