Last of three parts

FOR Ferdinand Marcos, failing to gain official recognition for Maharlika and subsequent war claims did not seem to matter. By 1947, he was already an economic advisor to President Manuel Roxas. By 1949, he was representative of the second district of Ilocos Norte.

By 1954, before his second reelection as congressman, he had married the beauty queen Imelda Romualdez. In 1959, he was elected senator, with his cousin Simeon Valdez replacing him as representative of the second district of Ilocos Norte.

Throughout this legislative phase of his political career, Marcos projected himself as an advocate for veterans’ affairs. Conveniently, within 1947-1964, several people who could have either corroborated or contested his claims of heroism during the Second World War had passed away. Roxas died in 1948. Gen. Jonathan Wainwright, commander of Allied Forces in the Philippines died in 1953. Gen. Douglas MacArthur, commander of the U.S. Armed Forces in the Far East (USAFFE), died in 1964.

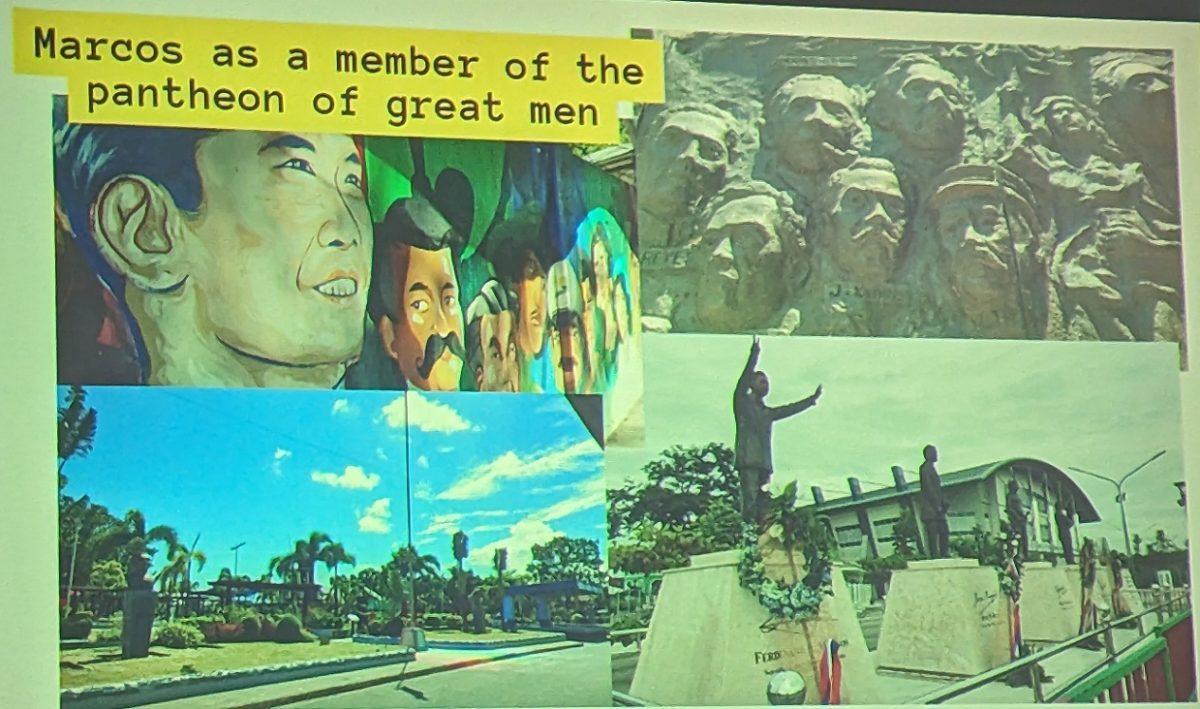

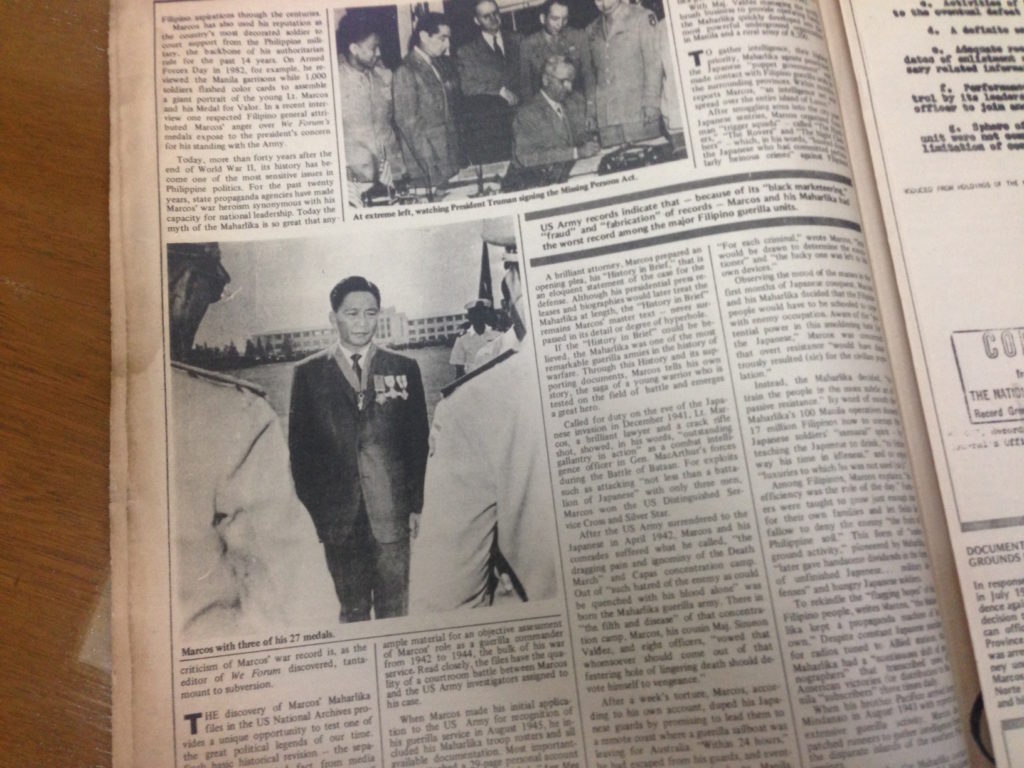

It was between 1963 and 1965 that the myth of Marcos the war hero was brought to new heights. As pointed out by the late Ret. Col. Bonifacio Gillego, it was in a single ceremony in December 1963 when Marcos received an additional ten medals—all from the Armed Forces of the Philippines—for his alleged guerrilla exploits.

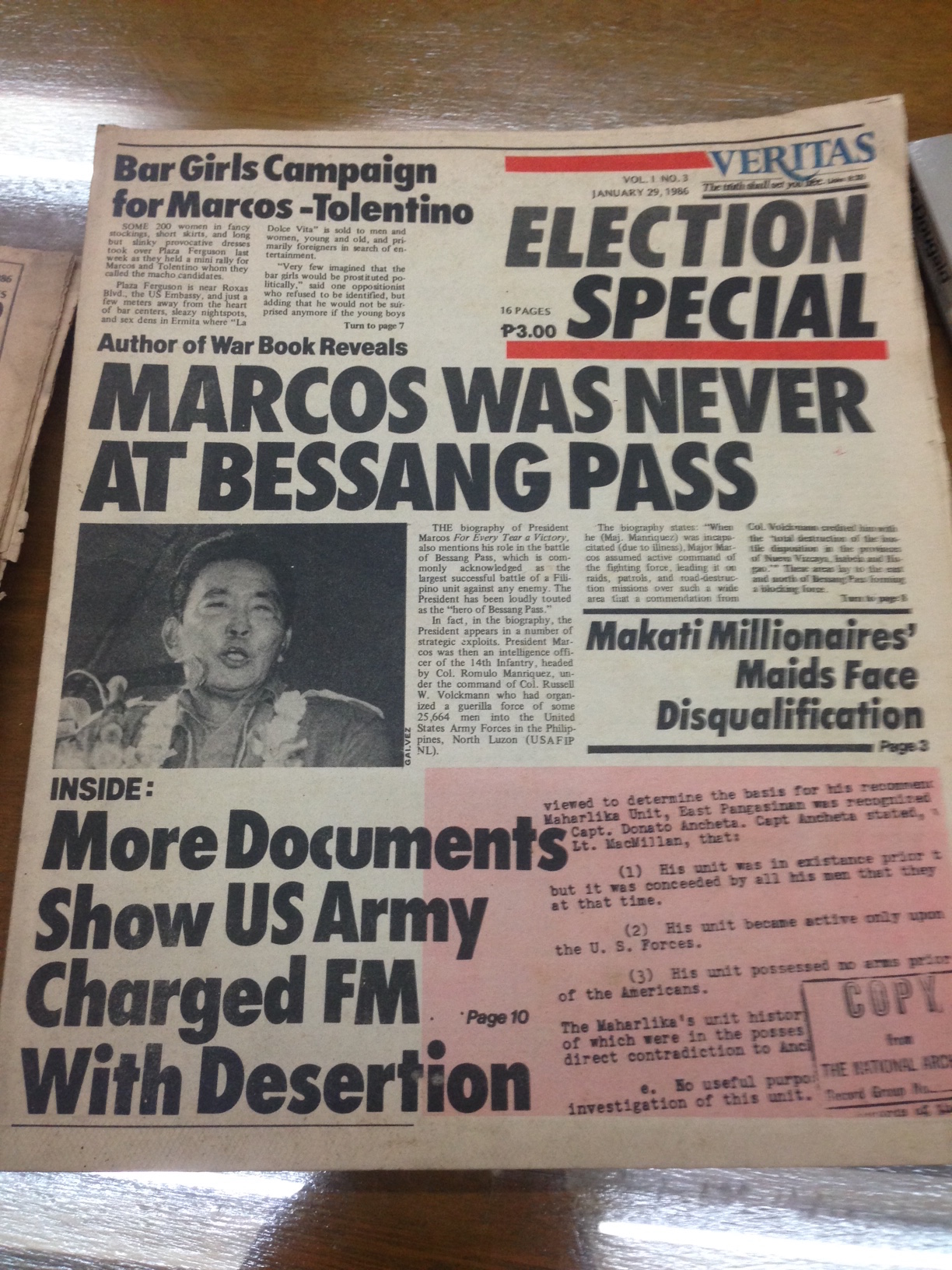

In 1964, Hartzell Spence’s For Every Tear A Victory: The Story of Ferdinand E. Marcos (later published as Marcos of the Philippines: A Biography) was released. Many pages of this tome are dedicated to revealing Marcos’s acts of derring-do, such as supposedly delaying the Fall of Bataan and fighting in the pivotal Battle of Bessang Pass in Cervantes, Ilocos Sur.

In September 1965—mere months before the elections—the film Iginuhit ng Tadhana was released. At the center of that film is an action-packed depiction of Marcos’s guerrilla activities, though it largely excludes his presence in both the Battle of Bataan (it does show him trudging along with other soldiers in the infamous Death March) and the Battle of Bessang Pass. A wordless scene where he is shown being awarded a medal by an American officer punctuates the film’s section on Marcos’s war activities.

Perhaps the people behind Iginuhit decided to tone down Marcos’s heroics because of certain reactions to Spence’s book. Writing in September 1965, Nick Joaquin ironically summarized apologia of For Every Tear saying the book was “mostly hocus-pocus” and “mostly bull.”

According to a 1974 Philippine News article, quoted in Primitivo Mijares’ The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos, then congressman Sergio Osmena Jr. told the Philippine Free Press in April 1965, “Those who actually fought at Bessang Pass say that they had never seen Mr. Marcos there or his whereabouts….There are those who attest to the fact that Mr. Marcos was during all that time at Luna, La Union, attending to military cases as a judge advocate.”

In File No. 60, there is a letter from Marcos dated May 1, 1945, with the letterhead of the GHQ of USAFIP, NL in Camp Spencer in Luna, La Union. There, he asks Colonel Russel Volckmann, C.O. of USAFIP, NL, to allow him to “return to Manila…to permit [him] to join [Ang Manga Maharlika],” as “the only reason for [his] being attached to the 14th Infantry [of USAFIP NL] was [his] inability to return to [his] own organization,” and that “[his] presence in [his] organization is indispensable as the secrets, documents and funds of the organization are in [his] possession alone.”

Volckmann, through his Chief of Staff, Lt. Col. Parker Calvert, immediately denied this request. According to Calvert, Marcos could not be transferred to Ang Manga Maharlika as it “is not among the guerilla units recognized by Higher headquarters,” and “it is therefore believed that his trip to Manila…to report to an unrecognized guerrilla organization would be futile.” On record, in the middle of the Battle of Bessang Pass, which lasted from January 8, 1945 to June 14, 1945, Marcos wanted a transfer to Manila.

Mijares also highlighted how Marcos is never mentioned in the writings of generals Carlos P. Romulo, MacArthur, and Wainwright, among others, even if Marcos’s hagiographers claimed that the latter two recommended Marcos for high military honors.

“Immediately after World War II,” says Mijares, “when Filipinos talked about their heroes, the names mentioned were Villamor, Basa, Kangleon, Lim, Adevoso and Balao of the Bessang Pass fame. Marcos was totally unknown.”

Mijares directed readers’ attention to several inconsistencies or impossibilities in Marcos’s biographies, but made no mention of File No. 60. This was because at the time, the records had not been examined by anyone for decades.

The journalists Jeff Gerth and Joel Brinkley reported in 1986 that the records were declassified in 1958 and donated to the U.S. National Archives in 1984.

Writing for the New York Times in 1986, Brinkley quoted a U.S. Army archivist saying in 1984 that File No. 60 remained classified due to the objection of the Philippine government, which during those times meant Marcos himself.

In 1980, a few years after Mijares disappeared, never to be found again, a book by Ret. Col. Uldarico S. Baclagon called Filipino Heroes of World War II was published. Gillego, in a series of articles published in WE Forum from November 3-4, 1982 until November 19-21, 1982, said the book contains an account of Marcos’ “super exploits,” referring to his alleged participation, as a veritable one-man army, in four major battles in March and April 1945.

Gillego noted that Baclagon based his accounts on official AFP documents—that is, the documents that gave Marcos the majority of his medals long after the war had ended. Gillego nevertheless faulted Baclagon for failing to corroborate these documents. Gillego did thorough verification, interviewing the 14th Infantry’s commanding officer Col. Romulo A. Manriquez, and staff and line officer Capt. Vicente Rivera.

Manriquez, Gillego says, was incensed by a claim that he served under Marcos. Furthermore, Manriquez stated that Marcos was placed in charge of civil affairs, given his legal background, and never fired a shot between December 1944—when Marcos first reported for duty in the 14th Infantry—and the time Marcos requested transfer to the headquarters of the United States Armed Forces in the Philippines, Northern Luzon (USAFIP, NL).

In contrast, Gillego describes a passage in Rivera’s memoirs describing Marcos, in March 1945, as having “fired at rustling leaves thinking that Japanese snipers were lurking behind them.” Gillego wrote that Rivera was certain that Marcos was not in the Battle of Bessang Pass since at the time of that engagement, Marcos was “already in the relative safety of USAFIP, NL headquarters in Camp Spencer, Luna, La Union.”

“On the circumstances that led to Marcos joining the 14th Infantry [in December 1944],” Gillego wrote, “Rivera had this to say: They knew of the presence of Marcos in the vicinity of Burgos, Natividad, Pangasinan. With Narciso Ramos [and] Cipriano S. Allas, Marcos organized his Maharlika unit with but a few [members,] not the 8,300 he claimed for back pay purposes. Marcos was on his way to La Union to inquire into the circumstances surrounding the death of his father Mariano Marcos.”

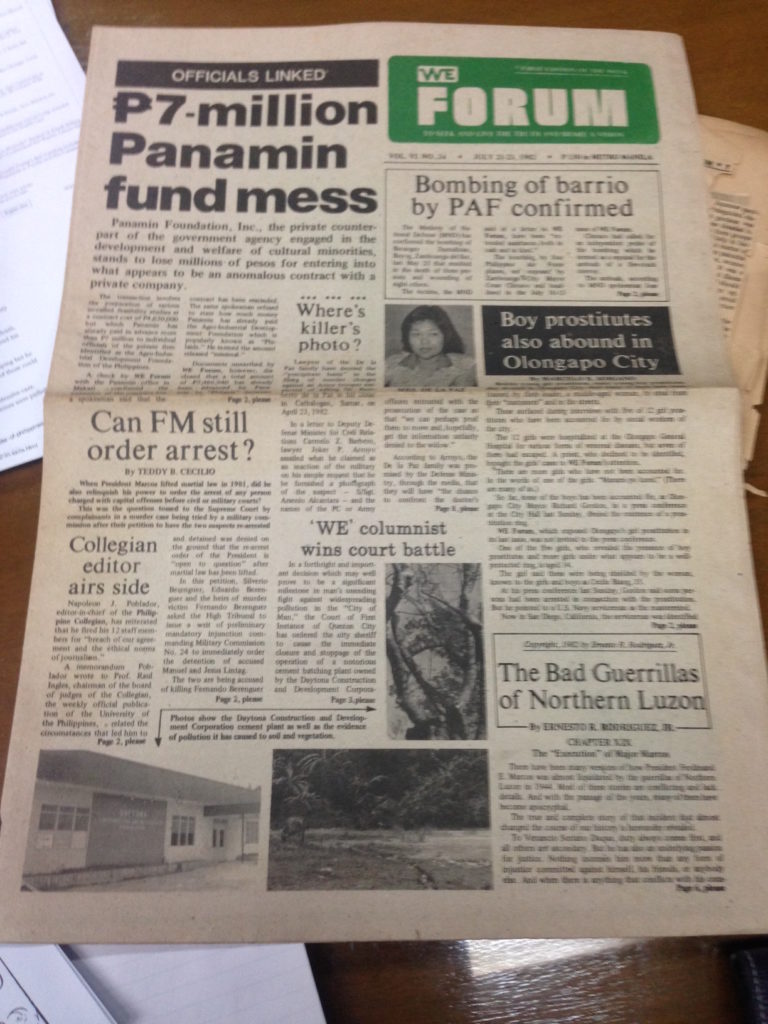

All this, Gillego was able to establish even without the damning evidence in File No. 60. Gillego’s WE Forum series was originally a 35-page monograph. It was the series that led to the jailing of the late Jose Burgos, WE Forum’s editor, and fourteen of his staff members for subversion and rebellion. By then, Marcos had already “lifted” martial law.

Yet there seemed to be no stopping the accounts that question Marcos’s claim to heroism. On December 18, 1983, John Sharkey, assistant foreign editor of the Washington Post, wrote the report “The Marcos Mystery: Did the Philippine Leaders Really Win the U.S. Medals for Valor? He Exploits Honors He May Not Have Earned.”

Sharkey spent 18 months of investigative work on the report and came to the conclusion as clearly as spelled out in the title of his report. He was not able to find “any independent, outside corroboration…to buttress a claim made in the Philippine government brochures that he [i.e. Marcos] was recommended for the U.S. Medal of Honor because of his bravery on Bataan.”

The historian Alfred W. McCoy took note that “when the Washington Post published fresh allegations challenging his medals in December 1983, not a single Manila newspaper dared to publish it.”

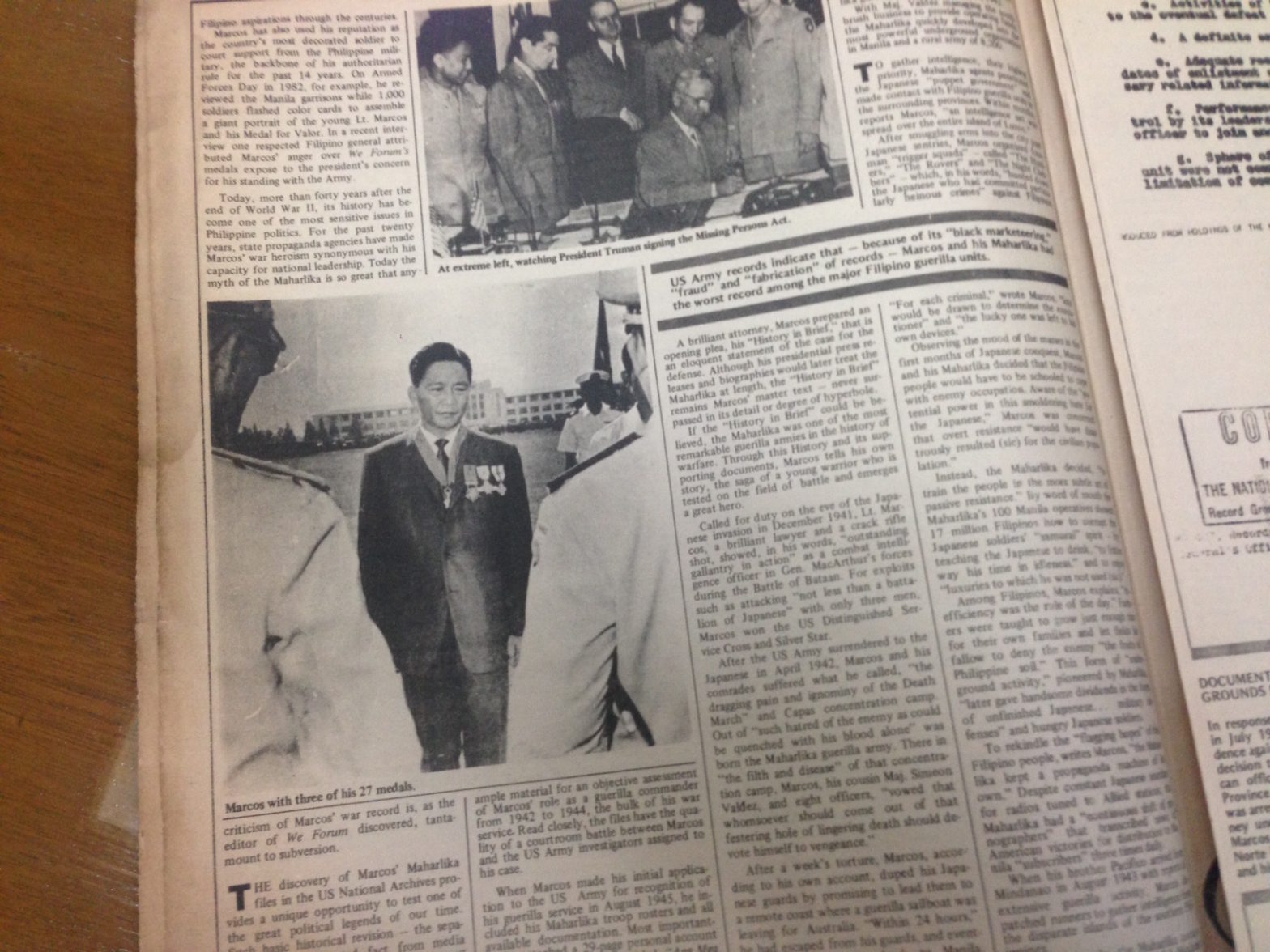

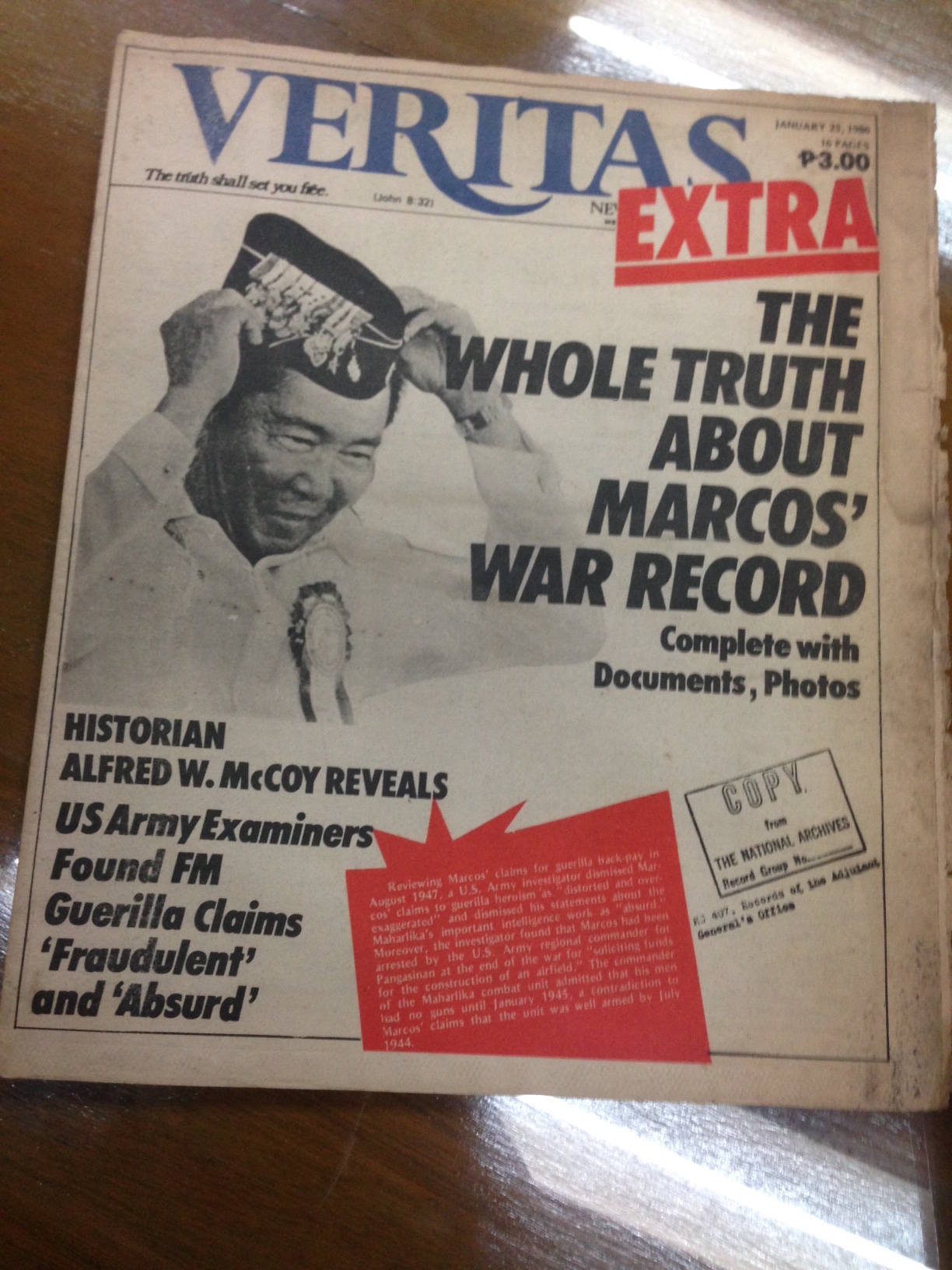

Come January 1986, shortly before the snap election in February, many of the contents of File No. 60 were splashed all over the pages of Veritas Magazine for the public to peruse. Accompanying photographs of the documents in the January 25, 1986 issue of Veritas was an article by McCoy, who found the Marcos files in the U.S. National Archives in Washington.

As reported by The New York Times a few days before the Veritas exposé, McCoy “discovered the documents among hundreds of thousands of others several months ago while at the National Archives researching a book on World War II in the Philippines.”

Originally published in the defunct Australian newspaper National Times, McCoy’s article echoed a lot of what had previously been stated by Mijares and Gillego and their sources, but had the advantage of being able to dismantle the Marcos myth as formulated by the man himself. McCoy gave particular emphasis to the document titled “Ang Mga Maharlika – Its History in Brief,” calling it Marcos’s “master text” on Maharlika.

McCoy described this document as being attached to Marcos’s first attempt to have Ang Mga Maharlika recognized in August 1945. However, the “cover sheet” describing File No. 60’s contents only mentions a history as being attached to Marcos’ December 18, 1945 follow-up letter.

In either case, it is curious that the document concludes with a reproduction of Ang Mga Maharlika’s disbandment order, which Marcos dated as being issued on December 31, 1945.

Marcos did seem to have a penchant for describing events as having occurred before they actually happened. McCoy notes that Marcos’s very first blunder was paragraph 3b of the August 1945 submission. In that paragraph, Marcos claimed, “In the first days of December 1944, [he] proceeded to the Mountain Province on an intelligence mission for General Manuel Roxas,” and that he was attached to USAFIP, NL since December 12, 1944 because “the landings in Lingayen, Pangasinan cut off [his] return to [his own organization, Maharlika].” The error was obvious even then; the first landing in Lingayen Gulf happened in January 9, 1945.

Thus, in the first indorsement of Marcos’s August 1945 submission, dated September 16, 1945, a Major Harry McKenzie said: “Par. 3 b. is contradictory in itself….Landings a month later could not have influenced his abandoning his outfit and attaching himself to another guerrilla organization.”

According to McCoy, “While the US Army was discovering that Marcos had not really played a key role in the resistance, the Philippine Army found evidence that his Maharlika combat unit had spent the war selling scrap metal to the Japanese military….In separate investigations between 1945 and 1950, the Philippine Army and US Veterans Administration collected affidavits and documents showing that the Maharlika’s Pangasinan unit had avoided combat and dedicated itself to dominating the black market trade in scrap metal and machinery.”

All these notwithstanding, this is what is written in the Department of National Defense’s profile of Marcos: “During the outbreak of the Second World War, Marcos joined the military, fought in Bataan and later joined the guerilla forces. He was a major when the war ended.”

The very same profile, word for word, can be read at the University of the Philippines ROTC’s website.

“History is an argument without end,” wrote the historian Pieter Geyl. It requires that one’s fidelity to truth and reason equals one’s boundless capacity to reassert the very same.

The Third World Studies Center is making public File No. 60. Read it here <http://uptwsc.blogspot.com/2016/07/file-no-60-marcos-maharlika.html>

(Joel Ariate and Miguel Paolo Reyes are researchers at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman. Judith Camille E. Rosette provided research assistance in writing this article. The digital copy of File No. 60 came from Ricardo T. Jose, Ph.D., the center’s director and UP professor of history, recently named the UP Alumni Association’s Distinguished Alumnus Awardee in Historical Scholarship and Research for 2016.)