Four years after Typhoon Yolanda devastated parts of Eastern Visayas, survivors are still clamoring for decent and livable homes amid government’s continuing efforts to rebuild communities.

A study by the nonprofit think tank IBON Foundation says out of 86 resettlement sites in the region, only 59 are energized while five have water supply.

It surveyed 1,500 Yolanda victims and found that most of them opt out of the resettlement areas provided by the government due to substandard quality of the houses, delays in water, power supply and lack of access to livelihood programs.

“Undelivered outputs, shallow outcomes and increasing vulnerability for typhoon survivors are proving that the Philippine government’s rehabilitation work in Yolanda-stricken areas is a tragedy,” IBON said in a statement issued at a media forum on Nov. 8, the fourth anniversary of the super typhoon.

Tacloban City in the aftermath of typhoon Yolanda in 2013. (File photo by Luis Liwanag)

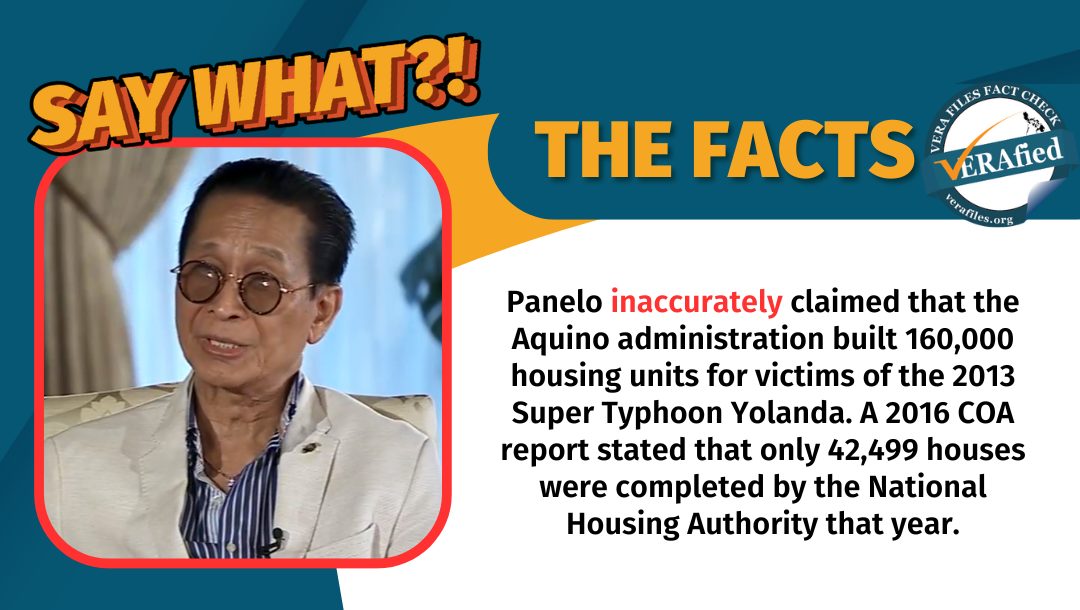

A day earlier, the National Housing Authority reported that 78,291 out of more than 205,128 housing units have been constructed, 33.5 percent of which are occupied by beneficiaries.

“Even the victims refuse to occupy the units. How will you occupy a substandard house? If it rains, you can hear the water because the walls are hollow. The water comes out of the floors,” IBON executive editor and research head Rosario Bella Guzman told VERA Files.

In some areas, local government officials even collect rent from relocatees, she said.

Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque, in a statement on Nov. 8, said Tacloban City, one of the hardest hit by the typhoon, is the “most successful model” in the government’s permanent housing program. The city, he said, has the most number of resettlement houses occupied at 10,703 out of 14,433 houses.

“That’s a shame,” Guzman said. “I will not be proud of 10,000 out of 14,000 after four years, and we’re talking here of resettlement which is the first thing you have to do when you get hit by a typhoon.”

After Yolanda, one of the strongest ever recorded, killed more than 7,000 and destroyed millions of homes, the Aquino administration in 2013 initiated the Build Back Better strategy in the government’s program to rebuild the devastated communities, where houses were to be built in safer areas.

President Rodrigo Duterte, disappointed with the slow pace of rehabilitation, said during a visit to Tacloban a year ago, that rehabilitation should have been completed in one year. Last August, he created an inter-agency task force to monitor Yolanda rehabilitation efforts.

Yet, the IBON study shows his administration is also far from closing inherited backlogs, even beyond the issue of housing.

At least 11,720 classroom, or 67 percent of the target, have been rehabilitated, while 1,790 new ones have been constructed. The delivery of livelihood programs is stalled at 47 percent, the study said.

While mostly agricultural, Eastern Visayas has restored only 111 out of 2016 irrigation systems, and re-fertilized only 14 percent of its coconut plantation area, it noted.

Nonprofit think tank IBON Foundation and disaster response organizations reported the status of Typhoon Yolanda survivors four years after it hit parts of Visayas in a media forum Wednesday. (Photo by Maria Feona Imperial)

Guzman said Eastern Visayas is an “economy of contradictions,” having posted the highest growth rate in terms of gross regional domestic product at 12.4 percent in 2016, amid an increase in informal work, stark landlessness and acute poverty.

Commenting on the study, Anakpawis Party-list Representative Ariel Casilao said the government forgot the basic nature of the region being dependent on agricultural products.

Agriculture, he said, was neglected in favor of what he called a “golden age of infrastructure,” referring to the Duterte government’s priority program.

Even as survivors cry for decent homes and livelihood, the study also pointed out that infrastructure is prioritized by the government to allow for market-oriented rehabilitation efforts.

Guzman cited the case of the P7.9-billion tide embankment project in Leyte, a four-meter seawall that will serve as first line of defense against a storm surge.

Based on reports, however, a storm surge during Yolanda reached up to seven meters.

Spanning 27.3 kilometers, the seawall, whose construction begins this year, will cut across Tacloban City and Palo and Tanauan towns.

Beyond disaster mitigation, it will serve as “tourist destination and generate economic benefits to typhoon-affected residents,” the Department of Public Works and Highways said in a news release.

Owen Migraso of the Center for Environmental Concerns said the project may effectively displace some 10,000 residents, most of them fisher-folk who have not yet been relocated.

In Catbalogan, Samar, another area hit hard by Yolanda, Guzman said a 440-hectare Sky City Mega Project is under construction, part of a new township being developed on a hill overlooking the entire city. It will house government offices, mall zones, hotels, residences and technology hubs, among others.

“Come to think of it, your government will be located in the middle of a business district—far from a storm surge and far from its people, too,” she said.