By DARLENE CAY

Fighting for press freedom is like flying a kite, some journalists found out today. Both have hits and misses and their share of disappointments.

Journalists from different media organizations flew about a dozen kites to commemorate World Press Freedom Day at the University of the Philippines Diliman Oblation Grounds.

Nine kites had letters that were supposed to spell out “free press,” but not all of them soared. An “s” got tangled in a tree and only the letter “e’s” in “free” took off.

High for Press Freedom’ activity in UP Diliman on May 3. Photo by VINCENT GO

But the journalists were undaunted. “We celebrate this day because we continue to unite and fight for press freedom despite the challenges media people face,” National Union of Journalists of the Philippines Director Sonny Fernandez said.

In its 2013 press freedom report released yesterday, the Southeast Asian Press Alliance (SEAPA) said that the Philippine press, despite a few positive strides, continues to be obscured by restrictive laws and the persistence of the culture of impunity.

The regional advocacy group said the Philippines is considered one of the Southeast Asian countries with “a relatively freer media” but this is eclipsed by the lack of solution to existing problems that plague the press.

“As a whole, [Southeast Asia] has moved backward on media freedom in 2012 with more restrictive laws being enacted by governments, while in many countries journalists and civil society continue to be threatened by violence,” SEAPA said in its report released yesterday.

In the Philippines, which is still considered among the deadliest places for journalists, the wheels of justice grind slowly for families of slain journalists, especially for the 32 killed in the Maguindanao Massacre in 2009. Last year, SEAPA also noted a continuing increase in attacks and threats to media.

Under Aquino

“There was little to be thankful about in the decrease of the number of journalists and media workers killed in the line of duty in 2012. Nothing has changed in the status of the cases against those accused of killing of journalists/media workers. The number of convictions remains at 10 since Benigno Aquino III became president in 2010,” SEAPA said.

The media in 2012 also had a tough time with a number of restrictive laws.

One such law is Republic Act (RA) No. 10173 or the Data Privacy Act, which gives the government power to monitor the processing of personal information in all forms and media of communication. Signed into law in August 2012, it prohibits the release of “personal information” in the name of privacy and national security.

Another law is RA 10175 or the Cybercrime Prevention Act signed into law in September of last year, which bears the most contested provision: online libel.

The implementation of the act was put on hold by a temporary restraining order issued by the Supreme Court, following the petitions filed by various individuals and groups.

And while these laws have been passed, the Freedom of Information Bill still has not.

“The likelihood of having a freedom of information (FOI) law passed under the Aquino government dimmed further in 2012,” the report read.

SEAPA said this would have complemented the administration’s good governance and anti-corruption campaign as it upholds accountability and transparency in the government. The 15th congress adjourned in February with the Senate passing its own version of the bill and the House of Representatives just barely starting plenary discussions.

The alliance however recognizes saw some “bright spots,” lauding, for instance, the live media coverage of the Chef Justice’s impeachment trial, establishment of new multimedia companies, improvements in the coverage of natural disasters, early preparations for the 2013 midterm elections and the blocking of the Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012.

These victories, it said, will remain “victories on paper” if the government does not move to act on the move to decriminalize libel and if the president won’t act on suggestions to speed up the investigation and prosecution of killings and attacks on the press.

The World Press Freedom Day, held on May 3 every year, is meant to celebrate press freedom and to remember journalists who died in its name, Fernandez said.

Global woes

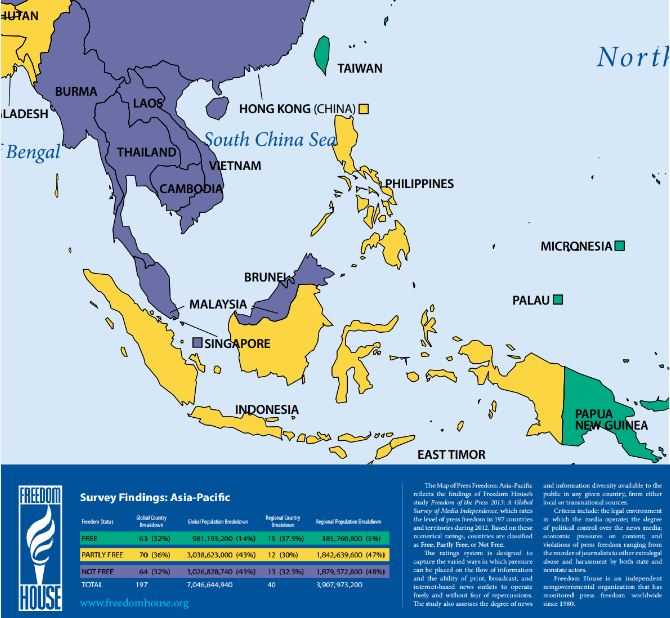

The U.S.-based research organization Freedom House yesterday also acknowledged slight improvements in press freedom in the Philippines, with its ranking moving slightly from 89th to the 88th.

An independent watchdog organization that monitors the exercise of press freedom in 197 countries, Freedom House categorizes countries and territories as free, partly free and not free. It categorized the Philippines as “partly free.”

On a global scale, the percentage of people who enjoy a free press hit its lowest in more than a decade, according to the 2012 Freedom House report. From 33.5 percent last year, only 32 percent of these areas were rated free.

The study further said less than 14 percent of the world’s population lived in countries with a free press.

The study also noted the “dramatic decline” in Mali, Greece and Latin America. Meanwhile, no significant change was seen in Middle East, North Africa,Tunisia, Libya and Egypt.

The study also noted the “dramatic decline” in Mali, Greece and Latin America. Meanwhile, no significant change was seen in Middle East, North Africa,Tunisia, Libya and Egypt.

The main stumbling block for press freedom is the political settings in these areas. With the emergence of the new media, it was also noted how this triggered a backlash from the rulers of authoritarian regimes by controlling all forms of media.

Other reasons cited for this decline were the effects of the European economic crisis to the financial sustainability of print media and ongoing threats from non-state actors such as organized crime groups. – With additional reporting by Vince Nonato

(Darlene Cay and Vince Nonato are University of the Philippines journalism students who are writing for VERA Files as part of their internship.)