By MARIA FEONA IMPERIAL

WHEELCHAIR user Jose Mari G. Vicentina, 46, arrived early at the Caloocan High School for a general assembly of persons with disabilities (PWDs) last July 22.

He was eager to attend the meeting, hoping he would witness the ceremonial signing of the ordinance creating the long-awaited Caloocan City PWD Affairs Office (PDAO), which is mandated by law.

But Vicentina was surprised that nothing had been set up: no tables and chairs, no stage, no documents and no mayor to sign them, not even a representative from City Hall to inform the participants that the event had been canceled.

“Pagpunta namin doon sa programa, walang kinatawan ang CSWD, wala ring kinatawan ang iba’t-ibang mga organization. Kami-kami lang (ang) naroon, so iba’t-ibang (PWDs) naghahanap (kung) sino bang haharap sa kanila (When we arrived at the program, there was no representative from the CSWD, there were also no representatives from the different organizations. We were the only ones there, so PWDs were looking for someone to welcome them),” he said.

Wanting to know what happened, Vicentina, who has muscular dystrophy, wheeled himself to the city’s social welfare department (CSWD) office more than a kilometer away.

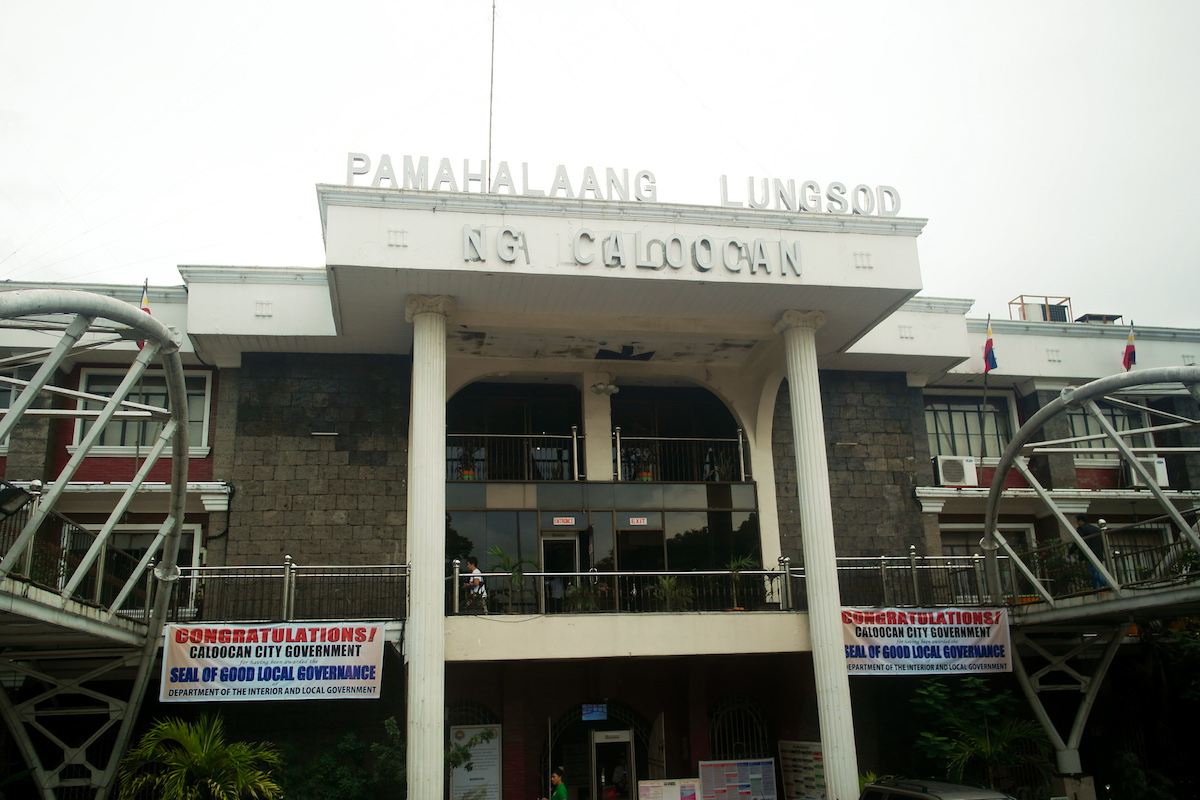

Without a PDAO that is mandated by law, the city’s PWD affairs fall under the social welfare department, a separate building located beside the city hall.

“’Yung kamay ko may kapansanan pero willing ako mag-participate kaya nagtiyaga ako (My hands have a disability, but I was willing to participate so I persevered),” he said.

Turns out, Vicentina, along with around 20 other Caloocan-based PWDs, missed the memo on the cancellation that was disseminated across barangays the day before.

Rosemary Reyes, focal person of the city’s PWD affairs, said the city government had to postpone for lack of time to prepare amid other activities to mark National Disability Prevention and Rehabilitation Week.

The P400,000 budget for the event was approved only that Monday, which gave them barely two days to procure T-shirts, transportation and food, among others.

Reyes, who also heads the solo parent unit of the CSWD, said she wasn’t able to send a representative to notify the attendees because they she had her hands full. “Wala ‘eh, dalawa lang yung tao. Sinong pupunta doon na personal(It is only the two of us here. Who will go there personally)?”

The PWD and solo parent units of the CSWD are manned by only three social workers, including Reyes.

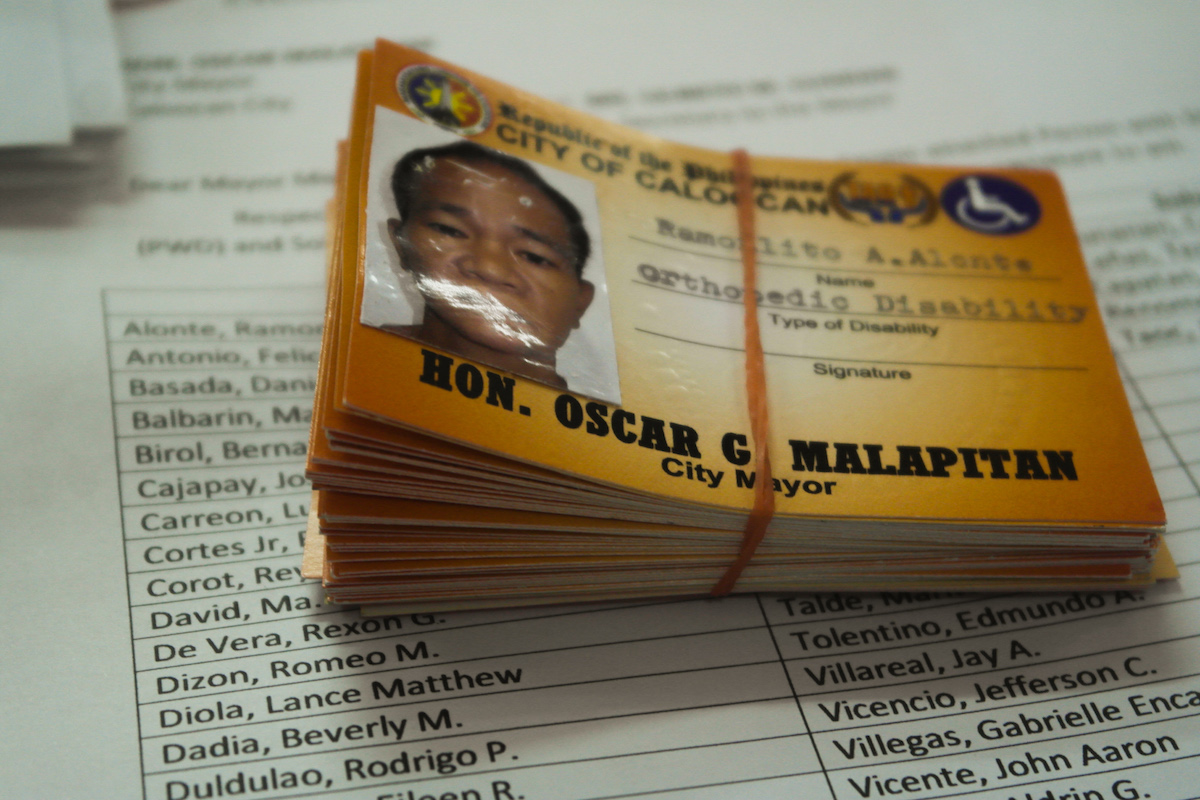

Based on official data, Caloocan City has around 12,000 PWDs but only 7,000 are registered and have PWD identification cards.

It takes time to process PWD IDs, interview PWDs and to encode their names in the master list.

“Kaya minsan di na namin ma-attendan (ang meetings),kasi pag nawala yung isa, pila-pila na, at hindi namin pwede paghintayin ang PWD, (That is why, sometimes we are no longer able to attend meetings, because when one is absent, PWDs end up queueing we cannot make them wait),” she said.

Reyes said the creation of a PDAO for Caloocan City, which is mandated by law, is yet to be signed by the mayor, but she was told by city councilors that the ordinance has “lapsed into law.”

This means that even if the mayor has not signed the papers, he has not expressed any disapproval, she said. They are only waiting for the mayor’s go-signal, she added.

“Actually, tatlong mayor na yan na lumalakad lang yung papel (There have been three mayors and the paperwork is moving very slowly),” she said.

As of writing, the implementation of the PDAO is still pending and is estimated to be built in 2016. The ordinance remains unsigned by the city mayor.

“Supposedly, dapat ngayong 2015. Pero hindi (naasikaso) dahil baka busy sa election (the office should have been built this 2015. But it didn’t push through maybe because people are busy with the coming elections),” Reyes said.

In the absence of an office, Reyes is still confident that PWDs are not neglected, saying they are prioritized as much as possible, especially in the annual budget.

For 2016, Reyes proposed a budget of P34 million during the city’s annual budget meeting in November. However, this includes only the expenses for monthly PWD programs such as leadership trainings, capacity building seminars, provision of assistive devices–but not the establishment of a PDAO.

Reyes said she has yet to check with the budget office if there is already an allocation for the PDAO.

In the meantime, Reyes said rather than taking the initiative, she prefers to rely on her boss, the head of the CSWD office, in raising the PDAO concern to the city mayor, saying it is the protocol.

“Hihintayin ko siya ang kumilos para dyan (I will wait for him to take action),” she said. “Alam naman niya (He knows) when is the right time to follow up with the mayor, the right time na pag usapan yon (to discuss the matter).”

Though there’s a long way to go, Reyes does not discount the progress of the CSWD and the city council in pushing for the establishment of a PDAO. She said the process will still need thorough planning and budgeting.

“Kung baga sa step, halimbawa, step 10, naka step two na kami (If there are 10 steps, we’re already on step two).” Reyes said.

Under Republic Act 10070, every province, city and municipality must establish a PDAO and designate a focal person. The law also states that priority in heading the office shall be given to PWDs.

Yet until an office solely dedicated to their concerns opens, wheelchair users like Vicentina, and even senior citizens, have to endure a very steep road that leads to the CSWD office.

“Doon sa CSWD, napakatarik naman pababa. Wala namang available na mag-aassist sa amin kaya minsan nahihiya kaming manghingi ng tulong sa mga tao para i-follow-up yung aming mga programa (In the CSWD, the road is very steep. No one is available to assist us so sometimes, we are ashamed to ask for help from people to follow-up the status of our programs),” he said.

There are also no ramps at the entrance of the office. The floor is lower than its facade, so Vicentina has to call the attention of guards or bystanders to assist him every time.

Sometimes, Vicentina also visits the Caloocan City Hall to direct his concerns to the city councilor who is in-charge of PWD-related affairs. Fortunately for him, the building has a ramp located at its façade – yet the exclusive entrance is always locked. It is only opened upon the request of a PWD.

So Vicentina has to get up from his wheelchair and lift himself on the stairs, one step after another, while a guard carries his wheelchair for him. This has been the scenario ever since.

Reyes said for the PDAO, the CSWD is eyeing a room located on the ground floor of the plaza in front of the city hall.

However, she is well aware that the place might not be accessible for people with orthopedic disabilities.

“Maliit para sa amin ‘yun kasi hindi siya accessible sa may wheelchair. Kapag may dumating na isang naka-wheelchair, okay lang, pero pag tatlo na sila, mahirap na doon (The space is small and is not accessible for wheelchair users. It can accommodate one wheelchair user, but not three of them),” Reyes said.

But for Reyes, a tiny space better than nothing.

“Hindi naman ako mamimili; basta maitayo yung PDAO, meron kaming panimula (I won’t be picky anymore; for as long as the PDAO is built, we have something to start with)” she said.

Reyes said local government units with PDAOs “have gone through the eye of a needle”prior to their milestones. She added that in other cities such as Mandaluyong, the establishment of a PDAO was initiated by PWDs themselves.

Meanwhile, for Vicentina, accessibility issues in the city, especially in the CSWD, manifest the “neglect” authorities have toward the situation of PWDs.

As much as he wants his voice to be heard, Vicentina feels that the interests of PWDs like him are being “limited” by certain barriers.

“Minsan, hindi namin maiparating ang aming mga (hinaing). Kahit gusto namin makialam, nalilimitahan kami ng hagdanan (Sometimes, we could not air out our [sentiments]. Even if we want to intervene, we are limited by the stairs),” he explained.

“Kahit may mga ideya kami, kahit gusto naming sumuporta, wala kaming magawa. Kaya sometimes they cannot blame us kung parang stagnant kami (Even if we have ideas, even if we want to support them, we can do nothing. Sometimes, they cannot blame us for being stagnant),” he added.

Even in his barangay, he said there are no specific programs for the welfare of PWDs. For instance, Vicentina said, the initiative of filing letter requests and project proposals for PWD activities solely rests on PWD organizations. His barangay has not matched this initiative.

Under Executive Order No. 417, one percent of the total yearly budget of national government agencies, including government owned and controlled corporations, should be allotted for funding PWD programs and projects.

In the Caloocan CSWD, Reyes said, the PWD affairs unit gets a share of around P1 million every year, which goes to medical services and startup businesses, among others. Based on the 2014 audit report of LGUs, the Caloocan CSWD had a total allotment of around P93 million.

Assistive devices such as prosthetic legs are provided through tie-ups with the University of the East Ramon Magsaysay Medical Center.

The CSWD also sponsors food, transportation and other logistical needs during meetings and activities.

Reyes, however, said despite these efforts, most Caloocan barangays are still not aware of the city’s programs for PWDs, including the mandatory PWD ID requirement. Sometimes, she sees a PWD who is a resident of Caloocan without an ID.

Reyes said problems in information dissemination are sometimes a result of internal conflicts among PWD groups in Caloocan.

This was evident in the case of the July 22 assembly. Besides the lack of time to prepare, another reason it did not push through was Reyes’ inability to get the cooperation of the Caloocan City Federation for PWDs.

The CSWD partners with the federation in its various programs and activities because it needs manpower. It is in charge of creating programs and preparing the budget, while the federation has to create associations and disseminate information among its members.

However, some associations “do not agree to work under the federation,” Reyes said.

Vicentina has his own grievances against the system being adopted by the federation. He said people with political interests run the system, and not all PWDs are represented.

“Hindi well-represented (ang PWDs). Ang pangangailangan (nila) hindi natutugunan, hindi natatalakay ang problema nararanasan ng PWDs (PWDs are not well represented. Their needs are not addressed, and the problems they experienced are not discussed),” he said.

As a social welfare officer assigned to cover more than 10,000 PWDs, Reyes said she can only do so much.

“Kung hindi sila magkakaroon ng cooperation sa bawat isa, paano ko sila maaabot? Nandito ako sa table ko, paano, bababa na lang ako? Wala na akong ginawa kundi puntahan sila (If they do not cooperate with each other, how will I reach them? All I ever did was go to them),” she said.

Reyes said a PWD needs to apply for membership in local PWD organizations under the federation to be included in the list of registered PWDs. The organization must register at the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Vicentina, however, finds this scheme problematic.

“Dahil sa kalagayan namin sila dapat ang lumalapit, dapat may consideration sila dahil sila yung nasa ganoong position at tungkulin nila yon (Because of our condition, they should be the one reaching us. They should have enough consideration because they are the ones in the position and it is their responsibility),” he said.

Reyes said the conflict among PWD organizations has extended even to the issue of the PDAO.

“Actually sa PDAO na yan, maraming gusto umupo na hindi qualified(Actually, there are many who want to head the PDAO office but are not qualified),” she said.

For Reyes, the PDAO officer should be a PWD who is a college graduate and has been a member of an association for at least three years, and competent enough especially in carrying out programs.

Vicentina said it is only right that PWDs man the office because they understand from first-hand experience the condition of those with disability better than those “who only work for the money.”

“Nagkaroon (na ang PWDs) ng idea kung paano gagawing less complicated ang buhay ng mga may kapansanan at hindi (sila) masyadong dependent kung kani-kanino, (They already have an idea on how to make the lives of PWDs less complicated and does not depend much on others),” he said.

But arguing over who will make up the PDAO personnel is pointless until there is an actual office to man.

“Kung talagang may malasakit sila sa kalagayan namin, sana gawin lang nila kung ano yung sinasabi ng batas, ipatupad nang maayos, magkaroon ng implementation ng PDAO (If they really care about us, they should do follow the law and implement a PDAO),” he said.

Vicentina also called on the local government to maximize the budget allocation for PWDs, especially on livelihood, rehabilitation programs and above all, education.

He said, “Kasi once na yung may kapansanan, naturuan mo ng iba’t-ibang paraan para sa sariling kabuhayan, ay hindi na sila aasa kung kani-kanino. Magiging self-reliant na sila (Once a PWD is taught different ways to earn a living, he or she will no longer have to depend on others. PWDs will become self-reliant).”