GENEVA, Switzerland — “Philippines, presente!”

Standing behind a tightly packed group of youth advocates and civil society organizations from around the world gathered before Geneva’s iconic Broken Chair monument, Gene Gesite Jr. made sure the voice of Filipino youth rang loud and clear.

It was the eve of the 11th Conference of the Parties (COP11) to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC), the treaty that guides global action against tobacco and nicotine harms.

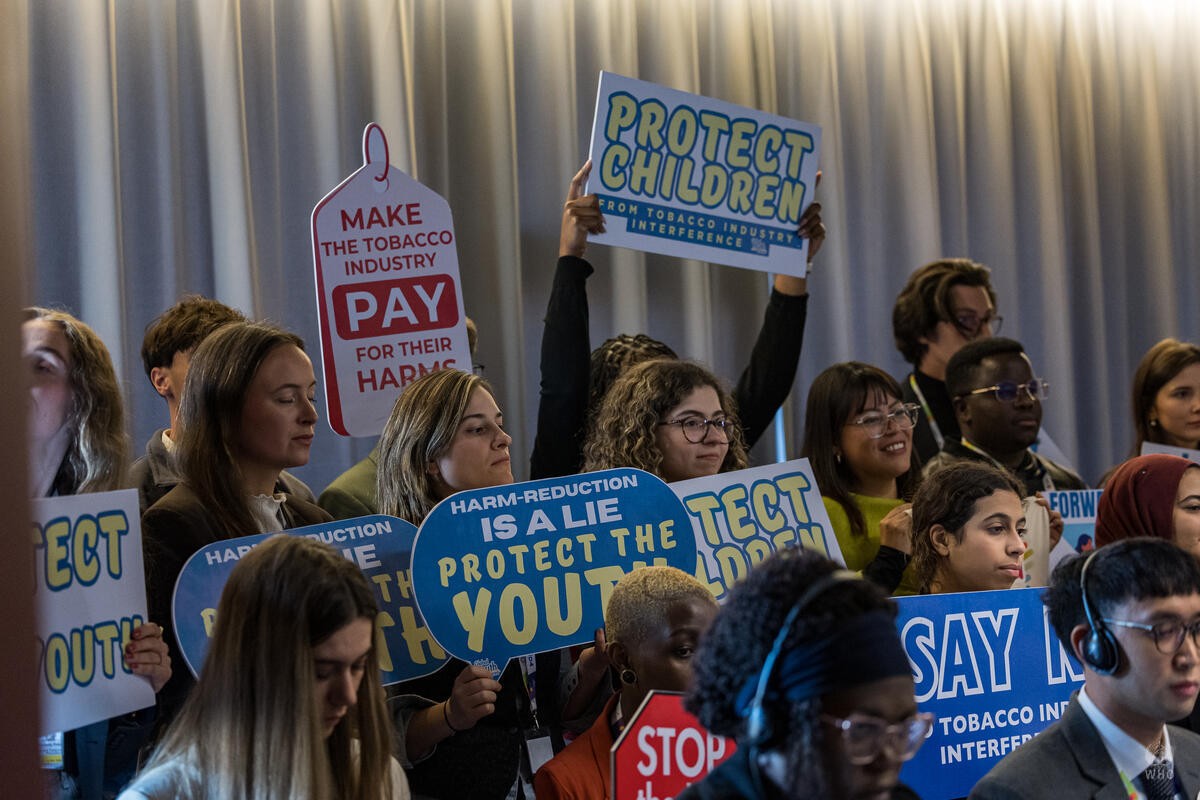

As delegates prepared to review progress and adopt new decisions, youth organizations mobilized outside the Palais des Nations to call out what they say is the biggest obstacle to effective tobacco control—industry interference.

The youth advocates could not have chosen a more symbolic stage to air their demands. Facing the gate of the Palais des Nations, the Broken Chair wooden sculpture —originally built to protest landmines but now a universal reminder of humanity’s unfinished work—has since been given different meanings to different people. It serves as a daily reminder that there is so much more work to be done to make the world a safe and humane place.

Banners flapped in the cold wind. Chants of “No more deaths from nicotine addiction!” and “Our health is not for sale!” echoed against the landmark sculpture. The message from the youth was clear: they are done being collateral damage.

Braving the biting onset of Switzerland’s wet winter, they called for a policy that is free of tobacco industry influence and the adoption of measures to make the industry pay for the harms it has caused the planet and human health in this generation as well as future generations.

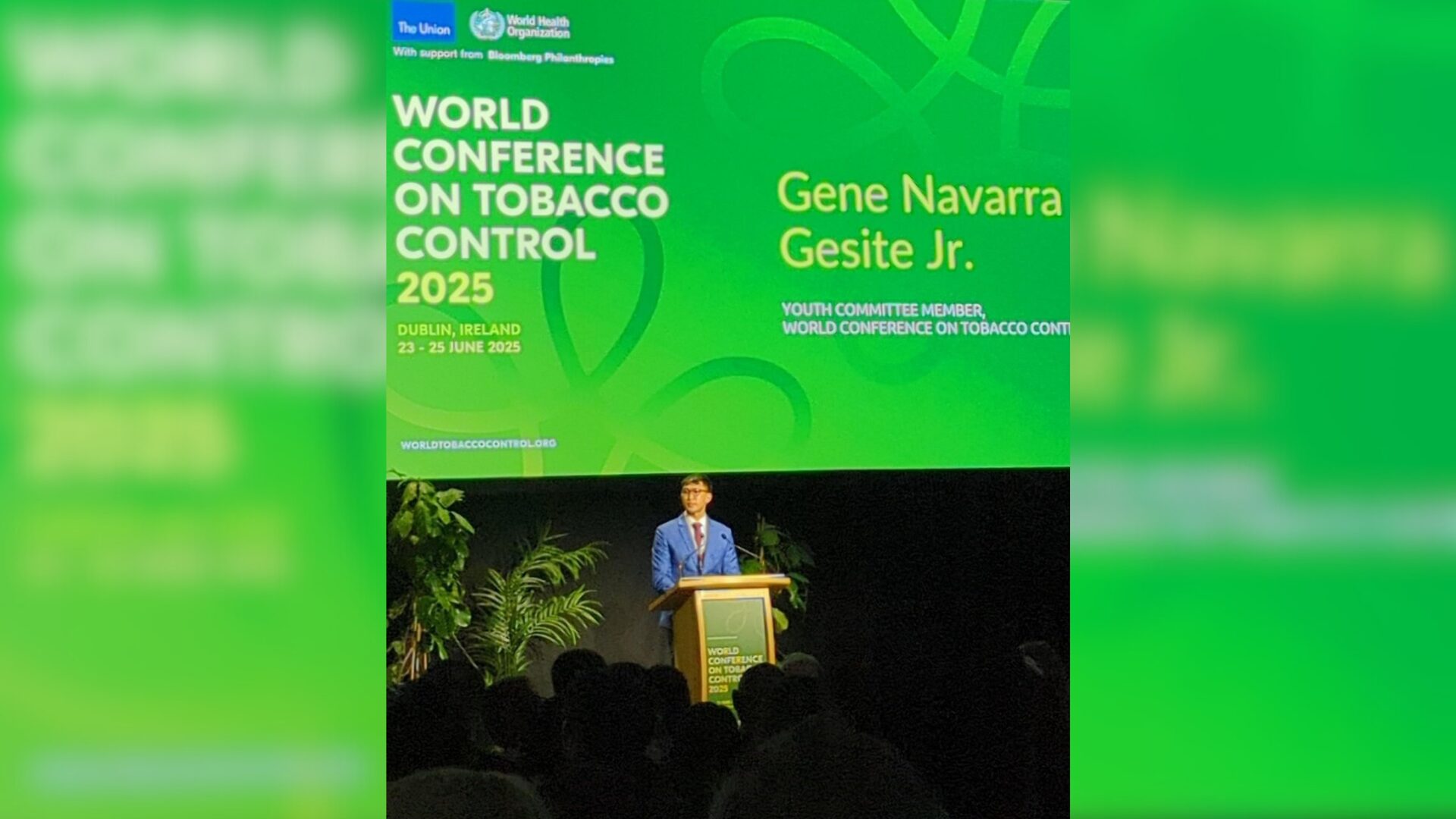

Gesite, a coordinator of Global Youth Voices—a youth movement spanning over 130 countries—was not only part of the street demonstration. For the first time, he was able to join other youth leaders inside the negotiations, witnessing firsthand how policy is shaped.

While the protest was loud, what Gesite witnessed inside the negotiation rooms was quieter, and more alarming.

Below is his first-person account of how the tobacco industry speaks:

“What stood out to me was this: the tobacco industry doesn’t even have to speak in the room to be heard.”

I attended my first Conference of the Parties (COP11) to the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) this November. For several years, I had been learning from advocates who have spent decades exposing the tobacco industry’s tactics. I had read articles, participated in training sessions, and worked with youth networks. But nothing prepares you for sitting inside the negotiations and hearing industry-aligned narratives woven into governments’ positions.

What stood out to me was this: the tobacco industry doesn’t even have to speak in the room to be heard. Its arguments were echoed, almost word-for-word, by the governments that are supposed to be protecting public health.

The Conference of Parties is meant to be a process where public health is protected and where Parties work collectively to safeguard people, especially young people, from addiction, manipulation and environmental harms. While many countries showed leadership and called for stronger tobacco control measures, there were also countries whose arguments closely aligned with industry narratives. They urged caution against strict regulation of new products, framing certain nicotine products as less harmful, or positioning these products as acceptable “alternatives.” These are the same strategies the industry uses to normalize new and emerging products.

Inside the meeting rooms, I sat with other youth delegates, observing the discussions, coordinating with each other, and offering support where we could. It was disappointing to see how casually industry buzzwords like “innovation” and “harm reduction” were repeated. Hearing these words in a treaty meeting intended to protect people from tobacco industry interference was a reminder of how pervasive and persistent these narratives remain.

For us, these dynamics carry real consequences. My generation is the one being targeted by new and emerging products through flavors, digital marketing, misinformation, and claims of being cleaner, safer, or more modern. Many of us grew up witnessing the harms that extend beyond health, including environmental destruction, toxic waste, and the continued exploitation of communities. Without strong regulation, youth will remain vulnerable to addiction and manipulation.

This is why youth organizations showed up at COP11 with a united message: we refuse to inherit a system built on addiction, pollution, and profit. In an open letter coordinated by the Global Youth Voices, we called for Parties to hold the tobacco industry accountable, protect policies from all forms of tobacco industry interference in line with Article 5.3, regulate all new and emerging products, address tobacco’s hazardous waste and environmental impact, and uphold young people’s right to health and a sustainable future.

Beyond the negotiations, COP11 also highlighted the importance of youth leadership. Young advocates asked questions, shared lived experiences, and grounded policy discussions in the challenges we faced in our respective hometowns. In side events and bilateral meetings, we emphasized that protecting youth is an obligation.

Youth participation at COP11 was greatly welcomed and encouraged by the delegates, WHO, and the WHO FCTC Secretariat. This was echoed by WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, who wrote on his X account: “I encourage all young people to stand up for their health and encourage their governments to strengthen protections against these harmful products.” In our meeting, Andrew Black, Acting Head of the WHO FCTC Secretariat, also reminded us that “Youth voices are actually critical… The strongest voices urging governments to take action for tobacco control will come from you – young tobacco control advocates.” These moments affirmed that youth engagement is necessary, though it must be strengthened through consistent access and avenues for meaningful contribution.

I also saw the dedication of civil society organizations who have been in this fight for years. Their work paved the way for us, making sure our voices are visible, credible, and influential at COP11.

If there is one message I hope governments take away from this COP, it is this: when governments adopt industry language, they are not protecting their people. They are reinforcing the one responsible for this global crisis.

Young people deserve better. We deserve policies rooted in science, equity, accountability, and our own lived experiences. COP11 reminded me that progress may be slow, but it is possible. And we will continue to show up until the world recognizes what youth have been saying all along: there is no future in tobacco.