Safety trainor Red Batario helps environment journalists identify sources of vulnerability.

Vera Files President Ellen Tordesillas was giving a background on the Earth Journalism Network to the 20 journalists attending a safety seminar when they heard a loud, insistent knock on the door.

Before they could process the distraction, an armed masked man barged into the room holding hostage another participant who was about to enter the room, and ordered everybody, “Dapa! Dapa! (Get down! Get down!) while gathering items – bags, cellphones, etc. – on the table.

Frightened, the participants ducked under the tables.

It was a mock attack that set the mood for the safety seminar for Filipino environmental reporters organized by VERA Files under its Environmental Reporting Project with Internews. It was conducted by Redmond Batario, executive director of the Center for Community Journalism and Development at Richmonde Hotel in Pasig City last Dec. 11.

Journalists face dangers but those covering environmental issues are “at greater risk of arrest, murder, assault, threats, abduction, self-exile, lawsuits, and harassment than their peers on some other beats.”

This is articulated by Knight Center Director Eric Freedman in a 2018 study entitled ‘In the Crosshairs: The Perils of Environmental Journalism’ where he said environmental journalists face greater dangers because controversies they cover “often involve influential business and economic interests, political power battles, criminal activities, anti-government insurgents, and corruption.”

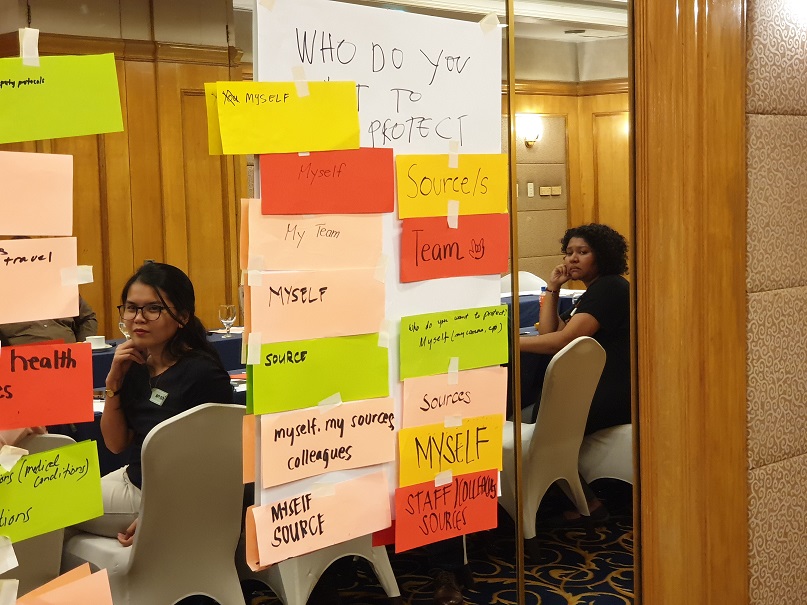

Participants forgot to mention their families.

“The work we do increases the risk we face,” Batario emphasized.

He said male journalists are more vulnerable to physical assault, threats, and arrest, while female journalists are more vulnerable to harassment, crime, and sexual violence.

Equipment that are necessary tools in reporting, like a laptop and camera, can be a vulnerability, he added.

A mobile phone is both a capacity and a vulnerability, Batario said. “If it is used discreetly and confidential information is coded, it is a capacity. If it is used loudly and confidential information is communicated, it is a vulnerability,” he explained.

Batario asked participants, “Who and what do you protect?” It is significant that the answers were “myself, sources, colleagues, team”. No one answered “family” which could also be a point of vulnerability for the journalist.

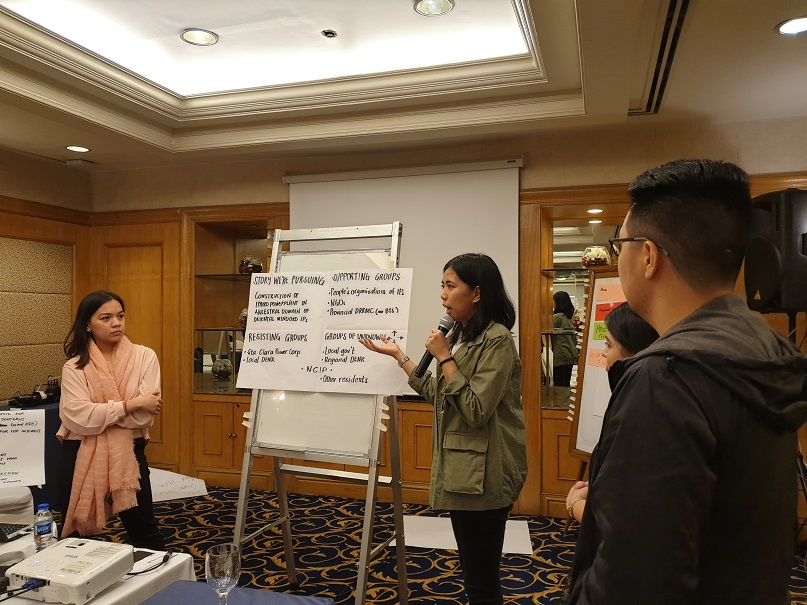

Zaneth Lago, Daniel Abunales, Arpee Lazaro, and Ellen Tordesillas assess the risks for a story they want to pursue.

Identifying Risks

Participants were asked to share experiences when they felt they were at risk.

VERA Files reporter Feona Imperial cited the time two plainclothes policemen turned up at the office purportedly to clarify a letter request for traffic–related data she had sought from the police headquarters a week earlier for a story she was doing.

The men, she said, asked for more information about VERA Files, such as funding and staff salaries. “One of them said they do not easily give out government data fearing this might fall into the hands of communists,” she related.

A journalist for Japanese agency Asahi, Johnna Giolagon, said: “The most insecure times I’ve felt during the coverage is the actual travel. I am always worried of a road accident or some other unfortunate event or disaster would happen.”

“When I was assigned to go to the Scarborough Shoal, I was worried that our boat would break down or a sudden storm would develop and the boat would capsize and we would drown,” she added.

Arpee Lazaro of PWD Philippines, who has a weekly program in Radyo Pilipinas, a government radio station, recounted the time his vehicle fell into a large open manhole.

“As soon as I was going around the car to find where I had fallen, three men came to my ‘rescue’ and I was taken aback because I felt threatened by their sudden appearance. I refused their offers of help and drove the car to the nearest gas station despite the blown out tire.”

Lazaro said he remembers the advice from the police that if you are in a situation where you feel like you might be in danger, best to extricate yourself from the scene. “So in my case, I did the right thing by leaving the place as soon as I could.”

The participants were divided into groups and asked to think of an environmental story and what threats they might face pursuing it, while also identifying groups that could provide them support.

Meeko Camba presents their group’s assessment of the situation in a place where they will be doing research for a story.

Improving situational awareness

Batario said it is important that journalists possess situational awareness, which he defined as “being aware of what is happening around you in terms of where you are, where you are supposed to be, and whether anyone or anything around you is a threat to your health and safety.”

He gave tips on improving one’s situational awareness:

1.Take an interest in the surroundings. Don’t just look, see. Take note of your surroundings, what feels different, to heighten your senses from potential threats.

2.Routes suitable in the morning may not be good for the night. Dimly-lit areas with little to no people are already potential signs of danger. As much as possible, take safer routes with people passing.

3.Check threat to health and safety. This can also be applied to post-reporting. Ask yourself: Is there anything around you that poses a threat to your health? To what extent? Also, is there anything you can do to safely reduce that threat in order that you can carry on working safely?

4. Know when you are under surveillance. Filter out coincidence, such as unusual activities and use your common sense.

5.Notify others on suspicious activities. This is to let them know of your sensitive situation, as well as to establish threat patterns.

6.Trust your senses. Sometimes, senses can provide the most immediate signal of possible danger.

Johnna V. Giolagon presents her group’s assessment of the risks involved in the story they will be doing.

Am I being followed?

If you feel you are being followed, but aren’t quite sure, do the following:

1.Vary your pace. This can further ensure if the follower is stalking you. It can also confuse the potential stalker, making his presence more obvious.

2.Change between quiet and busy areas.

3.Turn three sides of a block to confuse the follower.

4.Check through windows of shops to check the reflection.

Participants were advised to assess the situation in pursuing a story, reminding them that “No story is worth dying for.”

VERA Files trustee Rosario Liquicia shares her experience working for an international news organization where they are reminded no story is worth dying for.

This story is produced by VERA Files under a project supported by the Internews’ Earth Journalism Network, which aims to empower journalists from developing countries to cover the environment more effectively.