For 19-year-old Princess Luat, a casual trip to the pharmacy to buy birth control pills, was inconceivable.

“I was afraid and embarrassed at the same time, so it was always my boyfriend who would buy them for me,” says Luat, now 23 and a fourth year architecture student at a university in Manila.

Back then, it was a step into the unknown for the teenager. The side effects of the pills, she was told, may include vomiting, dizziness, and increased breast size, which are signs of pregnancy Luat did not experience at all.

“At first, I was afraid because I did not consult a doctor or an obstetrician… and I was hesitant… but the pills were helpful because I did not get pregnant. Nothing bad happened to me. But my parents were not aware,” she said.

Luat recalls how her mother flared up after seeing her pill stash. She was asked why she had those pills, though her mom stopped short of using the word sex.

In an interview with VERA Files, she recounted her unease and confusion in talking about her sex life with her family.

“At what age can you talk about [sex] with your parents or talk to them about what to do?,” she said in Filipino, adding that this kind of information is crucial but an unmet need among young people in the Philippines.

“That way you won’t go into a battle not knowing anything, (or thinking you know) only because you’ve watched something like that [porn], thinking that’s what you will experience, but not really.”

Like many of her peers, Luat would only open up about sexual health with her close circle of friends where there is no fear of being shamed.

Conversations on sexual health, such as contraception, are considered taboo in Filipino culture so most young people are left to their own devices and rely on unverified information sources such as pornography sites or advice from ill-informed peers, said Dr. Junice Demeterio-Melgar, executive director of Likhaan Center for Women’s Health.

Likhaan is a nonprofit founded in 1995 whose mission is to respond to “women’s expressed need for sexual and reproductive rights and health services.”

“[It is a very] stigmatized behavior if you’re sexually active, and you’re still a student. So who would want to seek help about a behavior that’s seen as sinful and not acceptable?” said

Demeterio-Melgar, a community-based health practitioner and an advocate for women’s health for over 25 years.

Recognizing the need for credible sexual and reproductive health education, Likhaan developed an online chatbot, powered by artificial intelligence (AI), called Kaiーshort for kaibigan or friend.

It was a 2016 project of two Canadian doctors, funded by the Canada Fund for Local Initiative and the Foundation for the Advancement of Clinical Epidemiology.

“Likhaan took over the bot training in 2019 and we opened it for public use in 2020,” Demeterio-Melgar told VERA Files.

Most of its users are teenagers and young adults who are sexually active or are intending to be. Likhaan said Kai has picked up about 2,000 inquiries through Facebook and Google Mail since it was launched.

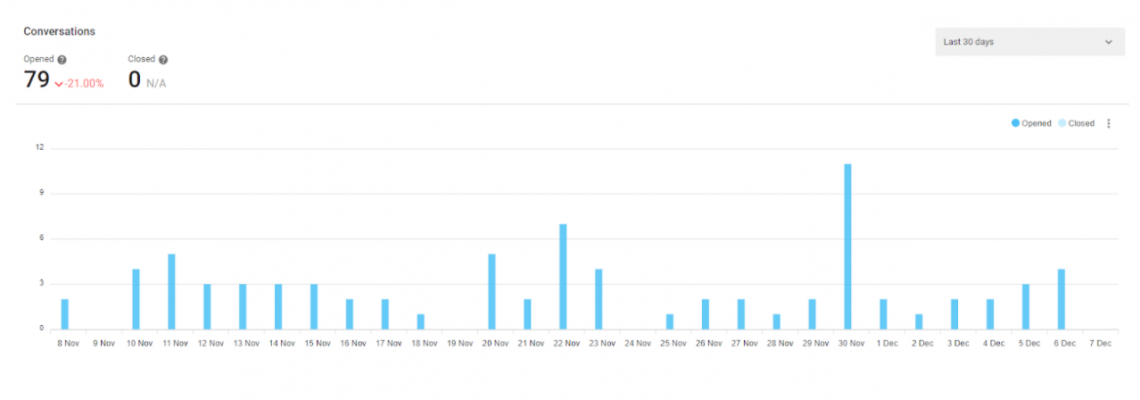

From Nov. 8 to Dec. 7 in 2021, Kai received 79 inquiries. Likhaan said “they do not have the funding to retain data longer than a month.” But it can be estimated that the AI-powered chatbot has picked up about 2,000 inquiries since it was launched in 2020.

The top inquiry is about contraception, but Kai can also answer questions on puberty, sexuality, LGBTQIA+ rights, maternal care, and sexually transmitted infections (STI).

Data from the Demographic and Health Surveys, funded by the USAID, showed that among Filipino teenage girls, who are from the 15 to 24 age group, about 12.2% reported having sex in 2017.

“There are a handful but we need to pay attention to them because they account for the high numbers of pregnancies that are all preventable,” said Demeterio-Melgar.

The country recorded more than 500 Filipino adolescent girls, aged between 10 and 19 years old, getting pregnant per day, based on a January 2020 United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) Policy Brief.

The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights noted in a 2020 report that around the world, one in four adolescent girls have an “unmet need for contraception.” This places them at greater risk not just for unplanned pregnancies but also for STIs, including the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and human papillomavirus (HPV).

Many users do not have any information about contraceptives, while some are misinformed about its dangers when used on a daily basis, according to Demeterio-Melgar. Young women are typically concerned about how birth control pills could affect their menstrual cycles.

“The temporary methods for family planning: pills, injectables, implant IUD, they’re all safe, and they are all good choices for young people,” she said, adding that most of these still require health screening, especially for hormonal methods of birth control, to understand the side effects.

“Correct use is the measure of how well you’re able to control your fertility. Not just use of any method, but correct and consistent use of that method.”

Using a ‘nonjudgmental’ persona

In Luat’s case, she had no clue what a birth control pill was until her boyfriend introduced it to her.

In senior high school, she said their teacher made no more than a passing reference to sex by saying, “You know this already.” “But a majority of us do not know what that is!”

In July 2018, the Department of Education (DepEd) issued policy guidelines for a Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE), in which teachers are directed to facilitate education on sexuality and sexual behaviors. The said order supports Republic Act No. 10354 or the Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health (RPRH) Act of 2012.

Demeterio-Melgar said the CSE is very important because it talks about a broad range of topics, including abstinence, consent, and respect.

“If you don’t really want to have sex, or you think, it is a complication for your life, if you’re a woman, you should be respected. And if you’re a man, your virility should not be made fun of, if you choose not to be sexually active,” she said, adding that this highlights the need for “empowering messages.”

“They need professional teachers to guide their decision-making and their comfort level about sexuality and contraception.”

In educating young people about sexual and reproductive health, Alfredo Melgar, Likhaan program director, said the “neutral or nonjudgmental persona of [the] chatbot may help young people overcome embarrassment or taboos.” The approach to messaging has to be succinct, inventive, and creative in order to get the attention of young users.

“As opposed to voice calls or face-to-face, the chat environment gives more distance, anonymity, and privacy,” he said, adding that it is “routine for teens” to initiate conversations past midnight.

In one exchange, a female user, anonymized by Likhaan, sent a message to Kai to inquire about intrauterine devices (IUD). She first used the “menu-driven” AI.

Kai then offered “human help” and the user began asking more personal questions: “Ma’am, pwede po ba ang implant sa 17-year-old?” (Are implants allowed for a 17-year-old?)

Apart from private chats, Likhaan puts out public posts through its Facebook page, whose authors are youth community organizers to “reflect top-of-mind concerns” such as mental health, failed relationships, or parenthood.

Melgar said, “The current combination of private chats and public posts will probably be the main features of a fuller, integrated initiative.”

“The two must work in tandem to maximize the strength and niche of each one. This is still a work in progress, but we have seen that it does work for a segment of the youth in the country.”

Luat, who now considers herself more aware of her options, says she will share what she knows with female peers who turn to her for advice. She will even refer them to Kai, who can make conversations on sexual topics less uneasy.

Empowering adolescent sexual health rights

Even with Kai and other similar online initiatives, Melgar explained that primary and secondary schools should remain as the “backbone” for sex education because they have the “widest reach” on the baseline content that young people need to know.

This, too, has to be coupled with access to health services, especially for poor women.

Likhaan currently operates seven clinics with the Department of Health (DOH) and PhilHealth accreditation and field outreach areas. Melgar said, “We rely on them [DOH] to provide actual services, including implants, IUDs, injectables, pills, condoms.”

However, Demeterio-Melgar said that the COVID-19 pandemic severely disrupted the service delivery to those who reach out to Kai for referrals to health clinics for contraceptive supply or other in-person guidance.

“That disruption means that [the] people [who] needed the services on a daily basis… piled up during the lockdown, they cannot go out. So you can really expect a surge, not just a COVID surge, but a surge in unintended pregnancy whether adult or adolescent,” she said.

The University of the Philippines Population Institute (UPPI) in an October 2020 technical report projected an estimated 18,200 unintended pregnancies among women in their reproductive age, from 15 to 19 years old, “due to community quarantine-induced service reduction.”

The DOH has reported that in 2020, a total of 8.08 million Filipinos used modern family planning methods. “However, there were also reports on dropouts which can be attributed to difficulties in accessing family planning services due to COVID-19 restrictions and lockdowns,” it noted.

In response to these numbers, President Rodrigo Duterte said addressing the rising teen pregnancies is an “urgent national priority” and signed Executive Order 141 in June 2021 to implement a “whole-of-government” approach in improving adolescent reproductive health.

“Protecting ourselves from COVID-19 is as equally important as shielding our families from the burden of unintended pregnancies,” said Juan Antonio Perez III, executive director of the Commission on Population and Development.

One key problem, Demeterio-Melgar said, is that the DOH and local government units insist on “written parental consent for those under 18 before contraceptive services are given.”

In the implementing rules and regulations of the RPRH Law, minors are not allowed to access modern family planning methods without written parental consent, unless they are teen parents or they had a miscarriage.

“We have a situation where government units (clinics, schools) have to refer to non-government organization (NGO) facilities to provide better contraceptive access to adolescents,” Melgar said.

In an assessment of country policies affecting reproductive health for adolescents, published in December 2018, Melgar and other researchers said this provision “restricts informed choice” and adolescents should have “control over and decide freely and responsibly on matters related to their sexuality, including sexual and reproductive health.”

They said “the rights of adolescents include access to life-saving interventions as long as they are mature enough to face the consequences.”

As the current health crisis persists, Likhaan sees Kai as an online companion and a “new platform” to deliver information, tools, and guidance to young people “so they can actively participate in caring for themselves.”

“It’s an empowerment component of health. It should be integrated into standard, high-quality care for all,” said Melgar.

This story is published by VERA Files under a project supported by the Internews’ Health Journalism Network’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights Story Grants for 2021.