At 15, Claire*, a rice farmer’s daughter, had set her sights on starting a business in the big city. A year later, she became a mother and had to set aside that dream.

It was early 2021. Her then-boyfriend was celebrating his birthday. Their province was under modified general community quarantine — the country’s most relaxed quarantine status then — and his relatives were at home. With festivities distracting everyone else, her 22-year-old boyfriend Jake * locked the bedroom door and told Claire he would not take her home unless she gave in to his desires.

Stop whining, he told her, nothing happens after the first time. That was Claire’s life-changing moment.

Eight weeks later, Claire’s sisters noticed her menstrual period was late. She admitted she kept her condition a secret from her family at first. “It’s my sisters who sent me to school, so that’s why I hid it from them,” she admitted in Cebuano. The teen was thankful that her family decided to accept her despite her situation.

Claire’s baby is now a year old, just learning to walk and talk. She lamented that her daughter may never meet her biological father since Jake abandoned them not long after the baby was born.

The couple tried to make it work at first. Claire moved in with Jake’s family when she was four months pregnant, while Jake found a part-time job at a local mall to pay the bills. However, despite the meager yet steady monthly income of P5,000 his job provided, Jake quit after two months because he didn’t like the work. Instead, he went to work for his best friend’s computer repair shop. He also tried to make a career out of his passion for the video game Mobile Legends but was unsuccessful.

To make matters worse, Claire said that being at home with Jake’s parents was extremely uncomfortable. While he was out working, Claire was left at home with her boyfriend’s parents. His mother refused to say a single word to her. “It’s a horrible feeling when you’re alone and the people around you don’t talk to you. I felt so unwelcome,” she said in Bisaya.

And whenever Jake felt that she was demanding too much, he subjected her to public humiliation. “Gi tawagan ko niya’g matapobre kay nagingon ko na dili namo ma sustenar ang bata anang mga daog niya sa Mobile Legends,” she said.

(He would call me matapobre because I told him that I wasn’t sure if we could sustain the baby with his prize money from Mobile Legends tournaments.)

Concerned for Claire’s mental health, her older sisters decided to take the young mother and her five-month-old baby under their wing. Jake stopped providing financial support three months later.

Claire is just one of 386,000 Filipinas who began bearing children between the ages of 15 to 19, according to preliminary results from the 2021 Young Adolescent Fertility Survey (YAFS5) by the University of the Philippines Population Institute.

The national situation

During the media forum on the Adolescent Pregnancy Prevention Bills last Nov. 29, Commission on Population and Development (POPCOM) Regional Director Jackilyn Robell shared that 155 babies were born to minors every day in 2020.

As a result, the Philippines loses approximately P33 billion in forfeited revenue every year due to adolescent pregnancies, according to a 2020 policy brief by the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA).

The economic consequences of teenage pregnancy can be traced back to the sudden stop to a young parents’ education. Preliminary results of the YAFS5 found that 8% of Filipinos aged 15-24 dropped out of school because they got pregnant or impregnated someone.

Claire is no exception. While she acknowledged the importance of education, the teen mom admitted that she had to discontinue high school. She wanted to pursue a degree in Business Administration, but needed to prioritize her baby’s needs over her own.

Edel Hernandez, president of non-government organization Medical Action Group (MAG), said in a 2021 interview with VERA Files that teenage pregnancy can disrupt the young parents’ education. Her organization began addressing the root causes of teenage pregnancy in Guiuan, Samar in 2015 through peer-to-peer programs and collaboration with local schools and health units.

Without educational opportunities, the young parents would remain in a cycle of poverty. “Babalik pa at babalik sila ng zero,” Hernandez warned. (They’ll keep going back to zero.)

The fear of falling into the cycle of poverty is why Anne* — a 17-year-old mother and Claire’s cousin — became a working student. Apart from navigating modular learning as a senior high school student, Anne also helped her mother run a buy-and-sell business. One can often see her in local buy-and-sell groups selling clothes, food items and — in some instances — hair.

Hernandez added that opportunities for continuing education must be supplemented with employment opportunities for young parents in order to escape this cycle of poverty. A social stigma toward young mothers has limited their opportunities.

As a result of the continuing rise of adolescent birth rates, former president Rodrigo Duterte declared teenage pregnancy a “national emergency” on June 25, 2021 through Executive Order 141 s. 2021.

State intervention

More than a year since Duterte declared adolescent pregnancy a national emergency, bills geared towards preventing teen moms were filed in both the House and Senate.

During a Nov. 29 media forum organized by the Reproductive Health Advocacy Network, AIDS Healthcare Foundation, and Young Feminists Collective, groups and government agencies called for the passage of two bills in Congress aimed towards preventing teenage pregnancy: House Bill (HB) 79 and Senate Bill (SB) 372.

HB 79’s principal author and Albay 1st District Rep. Edcel Lagman said that the country may fail to reap the benefits of a demographic dividend if it fails to curb adolescent pregnancy rates.

“No child should have to undergo the trauma of pregnancy and childbirth. No child should have to grow up overnight to take care of another human being,” Lagman said. (Read VERA FILES FACT SHEET: Is having 110 million Filipinos good or bad?)

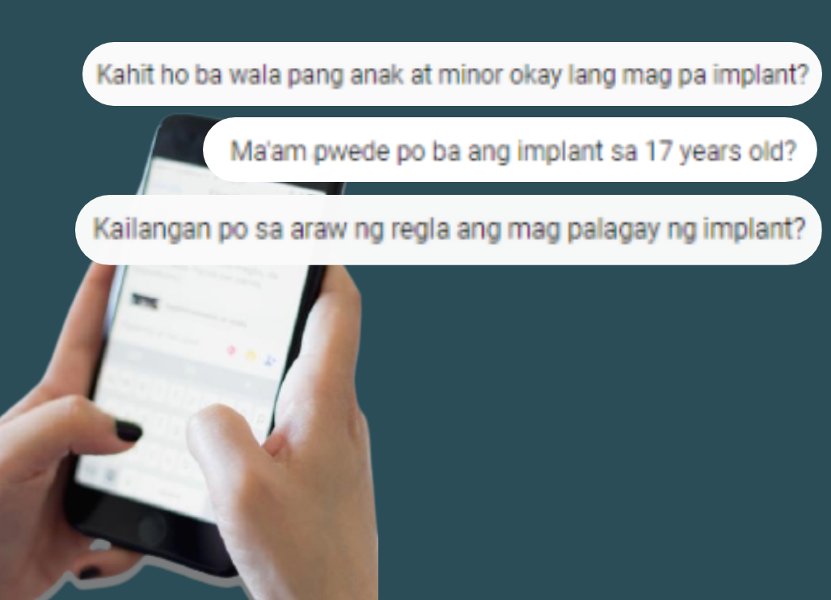

Both HB 79 and SB 372 aim to reduce the number of teen moms through the following: Age and context-appropriate Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE), accessible public and legal services for adolescents’ needs, and capacity-building of service providers to better cater to adolescent needs.

Both bills are currently pending at the committee levels. A hearing is scheduled on Feb. 3.

While Congress is set to decide on the fate of these bills, adolescent mothers like Anne break the societal stigma on young mothers like her by persisting through her studies and work. “I put [the work] in so I will show people that their judgments of me are not true,” she said.

Meanwhile, Claire hopes to continue her schooling when her daughter is older and earn the Business Administration degree she dreamed of. “The community usually thinks of teen moms like us as helpless. But if you see the teen moms here, I think we’re stronger. People like to gossip about us, and often the men would leave us, but I am still here and working hard to give my baby a good life. And it makes me a strong woman and mother,” she said in Cebuano.

*The real names of Claire, Jake and Anne were changed to protect their identity and privacy.