Victimized many times over, the pain and the trauma of the women who were subjected to palit-katawan (rape-for-freedom) in the time of former President Rodrigo Duterte’s tokhang cut very deep.

Palit-katawan translated literally as exchange of bodies is a term used both by the police and the researchers where the former use their power and authority to force women to have sex to save their partners from jail time or death. The phenomenon of palit-katawan emphasizes that men rape not because of biology but because of the gendered power dynamics that govern our social relations, i.e., authority and power are used to dominate and subjugate women’s bodies.

Rape is one of the most prevalent forms of violence against women (VAW). “A form of men’s expression of control over women retain their power,” according to the Philippine Commission on Women.

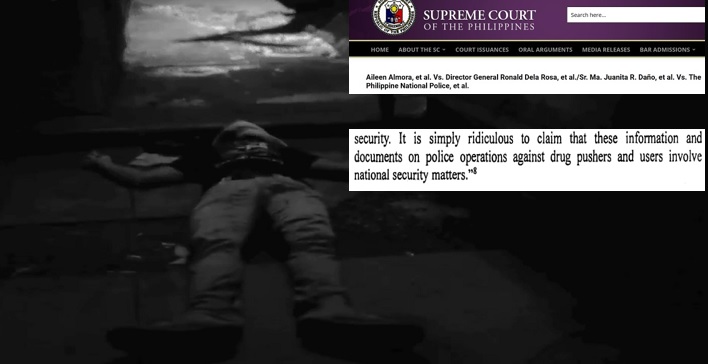

Tokhang, extrajudicial killings during Duterte’s war on drugs, enables the police to perform these horrendous violent acts with impunity, where “sexual violence,” as Jelke Boesten wrote in a working paper, “is a reflection of the abuse of power.”

Three women shared horrifying details of how the police coerced them to have sex.

Leslie, was abused by her uncle at an early age when she lived in Bicol. She ended up in Quezon City in search of greener pastures, but got into prostitution. When she met her current partner, she left prostitution. Her partner, she admitted, used illegal drugs to stay awake to earn more money from his construction job. Leslie narrates: “Sa trabaho din, kasi construction worker siya, kailangan niya para lumaki kita; kailangan niya OT (overtime) siya nang OT para mas malaki maiuwi nya, ‘yun. Ngayon, nauso nga Tokhang dahil kay Duterte, sumuko naman siya. Nag-rehab siya sa barangay. Lumaya rin. May pumunta nga sa bahay na tatlong pulis, sumuko na siya nun pero pinuntahan pa din kami…Saktong ako lang mag-isa kasi si baby ko nasa school pero dumating din asawa ko. Sabi ng pulis, para di raw siya kunin ulit, kasi parang gusto siya kunin ulit eh. Eh di ang ginawa ng pulis sa harap ng asawa ko kinundisyunan niya ako. ‘O kung gusto mo palit-katawan na lang.’ Sa harap ng asawa ko. Ayoko siyempre. Kaso no choice eh may mga baril sila eh” (It’s [illegal drug use] because of his job, he’s a construction worker that’s why, he needs it to earn more, he needs to go on overtime, so that his take-home pay becomes bigger. When Tokhang was implemented by Duterte, he [my husband] surrendered to the police. He underwent community-based rehabilitation and was eventually released. There were three policemen who went to our house, even though he already surrendered, the police still went to our house. Incidentally, I was the only one at home because my daughter was at school, but my husband did arrive. The police said, so that they won’t have to arrest my husband—because they looked like they wanted to arrest him again—the police, in front of my husband, gave this condition: “If you want, “exchange bodies.” In front of my husband. Of course, I didn’t want to. But I had no choice because they had guns.”).

Leslie continues: “Lalong sariwa yung nangyari sa akin porke nanggaling kami sa ganung lugar, naging biktima ng prostitusyon, parang ganun na lang kami babuyin. Binababoy ka nang sobra-sobra” (It brought back memories of what happened to me, just because we came from that kind of place, having been victims of prostitutions, like they [the police] can just easily abuse us. You get terribly abused).

Still Leslie: “Hetong anak ko walang alam. Masama loob ng asawa ko. Tapos nagtatago siya ngayon kasi pinagbantaan pa kami… Ang sabi sa akin, kapag ganyan, nagsalita ka, lahat ng kamag-anak mo patay rito [Quezon City]. Kilala kita. Kaya kami nagpunta ng Bulacan. Ang kinakainisan ko pa, sumuko na siya, nag-rehab na, tapos ganun pa din. Talagang pilit, gusto pa rin siyang patayin siguro. Bakit pa pupunta pa ng bahay at kukunin siya ulit eh okay na siya, galing na siya rehab eh” (My daughter does not know anything. My husband is upset. But now, he’s in hiding because they threatened us…They told me if I talk, all my relatives [in Quezon City] will be dead. That they know me. That’s why we moved to Bulacan. What upsets me is that my husband already surrendered and underwent rehab, and it’s still the same. They keep on insisting, it could be that they still want to kill him. Why would they go to our house and arrest him when he’s already okay, he’s been to rehab already).

Jean Enriquez, executive director of CATW-AP, facilitates the Psychological First Aid (PFA) session in 2018. PFA is a feminist tool used to initiate collective healing, surface individual stories related to tokhang, and assess the women’s immediate needs. Photo by Mary Ann Manahan

Mae, 31, has a similar story. She was in a bar in Pangasinan and ended up in Olongapo. She learned to use illegal drugs to numb herself from the sexual act—sometimes violent acts performed by paying customers. She has since stopped using illegal drugs and have tried to leave prostitution to start a new, better life: “Pampakapal ng mukha. Tapos ano minsan pag ‘yung customer mo nagagalit, sasaktan ka. Kapag ayaw mo naman, yung mamasan mo sabihan ka, ‘Bakit ka nag-iinarte, ang arte-arte mo eh ‘yan naman pinasukan mo. Wag ka na mag-inarte kasi yan ang pinasukan mong trabaho.’ Siyempre sinong tao ang gugustuhin mong mag-ganun diba? Tapos noong nag-18 na ako, dun ko nakilala yung asawa ko. Okay naman kasi mabait siya. Siya naglilinis ng bahay, minsan kapag pagod na pagod ako, ‘Yan tulog ka na lang dyan,’ minamasahe ako. Sa kapitbahay kasi, tinutukso siya, ‘Ano ba yan? Natitiiis mo ba yang ganyang asawa?’ Kaya nabarkada siya, nag-ganyan na din po siya [droga], hanggang inimbitahan na sa barangay. Sumurender naman kami sa barangay. Tumigil na naman po siya ” ([I used illegal drugs] to numb my feelings. Then sometimes if your customer gets angry, they hit you. If you don’t do as they please, the pimp will reprimand you, ‘Why aren’t you cooperating when you were the one who entered this? Stop being uncooperative because this is what you signed up for.’ Of course, nobody wants to do that, right? Then when I turned 18, that’s when I met my husband. It’s okay because he’s kind. He cleans the house, sometimes when I’m very tired, ‘Go to sleep,’ he’ll massage me. Our neighbors ridicule him, “What the heck? How can he take in a wife like that?” So he got into some bad company. He also got into illegal drugs, until he got invited by barangay officials. We surrendered to the barangay. He stopped [using drugs]).

Noong 2016, bandang October, nandun na itong asawa ko, lumabas, hinuli siya ng pulis kasama ng kaibigan nya, yung kaibigan niya nakatakbo. Tatlo silang magkakasama eh sabi nung kaibigan niyang nakatakbo, pumunta sa akin. Sabi niya, beh, anuhin mo asawa mo, pinaghihinalaan na nagbebenta. Pinaghihinalaan lang pala. Pagdating sa presinto kinasuhan na siya na dealer daw ng drugs kasi nakitaan daw siya ng pera saka droga. Sabi ko manong pulis baka pwedeng gawan ko na lang paraan ‘yang hinuli niyo asawa ko. Sabi niya, ‘May mga blotter na kayo saka dati na kayong gumagamit.’ Tapos di sabi nya, ‘O sige ganito na lang.’ Hinila nya ako sa gilid, ‘Magbayad ka sakin ng Php17,000,’ sabi nya. ‘Pero kung Php39,000, hindi ko na ikukulong asawa mo.’ Dalawa sila [na pulis]. Tapos sabi ko, ‘Pera ko Php10,000 tapos Php1,000,’ binigay ng kaibigan ko. Pambinyag ko nga ‘yun. Sabi niya, ‘Kulang iyan, ‘yung natitira sama ka na lang sa akin.’ Kaya sumama ako sa kanya ng ilang araw…tapos pagkatapos ng nangyari ‘yun hinagisan na lang ako ng pera. Sabi niya, ‘Umuwi ka na lang sa bahay nyo.’ Tapos ang ginawa ko ‘yung mga anak ko kinuha ko dinala ko, tinago ko. Tapos sabi ko sa asawa ko, ‘Magtagu-tago ka na muna’” (In 2016, around October, my husband was outside when he was arrested by the police with his friends. There were three of them, and one of his friends who escaped came to me. He told me, “Beh [Filipino pet name for a female friend], help out your husband, they think he’s a dealer.” It turns out to be merely a suspicion. At the precinct, he was already charged with drug peddling because he was found with money and illegal drugs. I asked the police if I can find a way to fix it because it was my husband they arrested. He told me, “There’s already a police blotter filed and you’re long-time drug users.” Then he said, “Okay, we can do it this way,” he then pulled me to one side, “Pay me Php17,000, but if you pay Php 39,000, I won’t put your husband in jail.” There were two of them [the police]. I told him, “I only have Php 10,000 and the Php 1,000,” which was given by a friend for my child’s christening. He said, “That’s not enough, for the remaining balance you can come with me.” So I went with him for a few days…After that he threw a few peso bills at me. He told me, “Go home.” When I got home, I took my kids and went into hiding. I also told my husband to lie low and hide).

Among the three women who experienced “palit-katawan” in the hands of the police, Cheryl is the youngest at 28. Originally from Zamboanga, she migrated to Caloocan as a domestic worker when she was 18 years old. But she did not get along with her boss and left her job. She then met her husband who took her in. She admits that they both used shabu at some point, but stopped when they had a child together. At the time of the PFA session (psychological first aid conducted by authors Enriquez and Rosales as CATW-AP, one of the first women’s groups that assisted families of Tokhang victims), she was at a massage parlor in Parañaque as a masseuse and was forced into prostitution by its owners. Cheryl lost her husband to Tokhang: “Yung asawa ko po sumuko sa pulis. Nasa drug list po kasi. Pero nakalaya rin. Kasi yung pulis po, dalawa sila. Nakursunadahan ako. Sabi nila, papalayain asawa ko kung sasama ako sa kanila. Ayun po, wala po akong nagawa kasi wala naman akong pantubos. Sumama po ako. Tinutukan po ako ng baril at tinakot na papatayin ang mga anak ko pag nagsumbong ako. Wala akong pinagsabihan, ngayon pa lang po.” (My husband surrendered to the police. Because he was in the drug list. But he got released. Because two policemen, they took a liking on me. They said they will release my husband if I go with them. I couldn’t do anything because I didn’t have the money to pay for bail. I went with them. They pointed a gun at me and threatened me that they kill my children if I go to the authorities. I haven’t told anyone until now).

“Tapos, ma’am, lumaya asawa ko. Magbabagong-buhay na po siya. Noong 2016, Agosto po ata, magkakasama po sila sa trabaho [referring to other two victims], sa construction po. Hindi na po umuwi nung ano ma’am eh, nung hinatid po namin ng Sabado ng gabi. Nalaman ko na lang po na sinalvage na asawa ko, pinahirapan nila” (Then, ma’am, my husband got released. He was supposed to turn his life around. In 2016, I think in August, they [with two other victims] were together at the construction site. He didn’t come home after we brought him to work on Saturday night. I just found out that they killed my husband, they tortured him).

“Yung isa pong pulis na gumamit sa ‘kin, naging abuser ko. Inulit na naman ang panggagamit sa akin. Masakit para sa akin. Pero nagtitiis ako para sa mga anak ko” (The police who used me for sex became an abuser/buyer [at the massage parlor]. He used me again for sex. It pains me. But I endure it for my children). Cheryl left her the massage parlor in Parañaque after the PFA.

The stories of Leslie, Mae, and Cheryl illustrate how women in prostitution are exploited, revictimized and retraumatized by the police and how the police use their power to dominate, threaten, and abuse them. CATW-AP’s study (Enriquez and Rosales 2019) also documented nine more cases of “palit-katawan” by the police, in which prostituted women were subjected to lewd, dehumanizing sexual acts in exchange for the life of or release of their partners from jail, as well, as the women’s own freedom. This is a continuing practice by the police who coerce women, in street prostitution, to have sex with them. These prostituted women used to be arrested on grounds of the Revised Penal Code Article 202 that criminalized them despite the Anti-Trafficking Law. Under Tokhang, police officers further use their knowledge of the drug-dependency of prostituted women (i.e., they use it to numb themselves) as leverage to force them into having sex. Revised Penal Code Article 202 as amended was eventually repealed in 2022 with the passage of the Expanded Anti-Trafficking Law (RA 11862) pushed for by CATW-AP.

Understanding the gender-based inequalities and stereotypes where sexual violence is grounded allows us to see that poor women whose partners may be in the illegal drug trade and drug-induced women in prostitution—often seen as damaged goods—are seen as properties of men and that punishing these women is but acceptable under the framework of Tokhang. These women victim-survivors are not collateral damage but clear targets of state-sponsored violence, i.e., palit-katawan as a form of VAW.

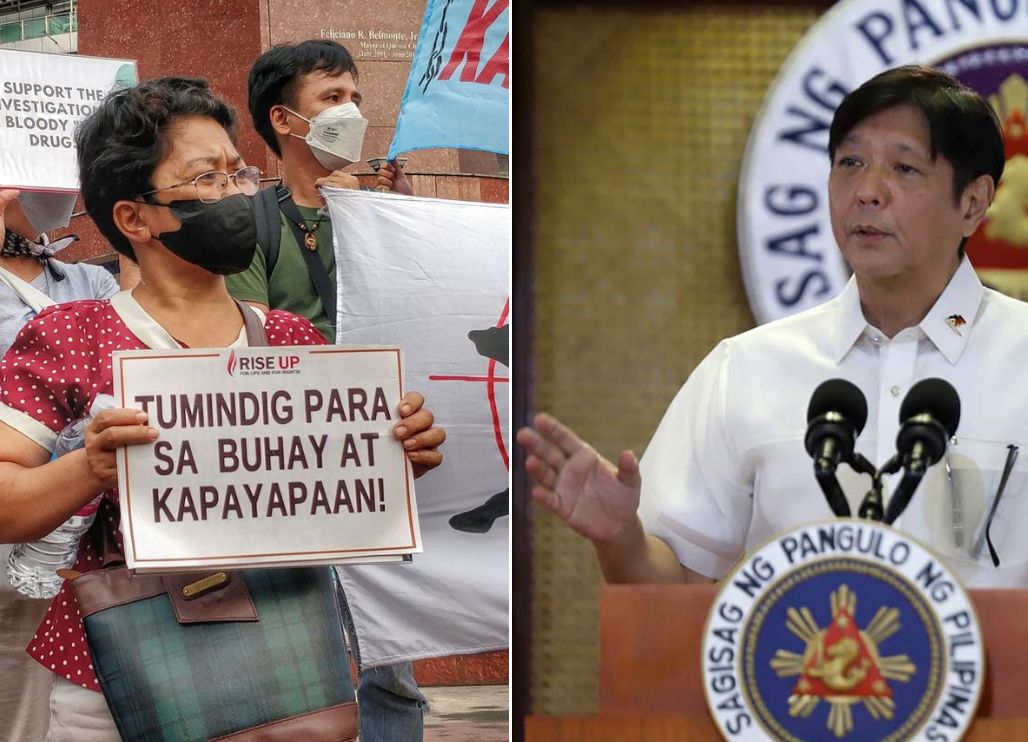

March has been declared as Women’s History Month “to recognize Filipino women’s contribution to the struggle for national independence, civil liberties, equality, and human rights.”

Commissioner Faydah Dumarpa of the Commission on Human Rights, in a statement for the 8th Purple Action Day last March 1, emphasized that “Purple Action Day has always been a space for making women’s voices heard, it has always been a space to seek accountability, to resist, and to surface women’s urgent issues.”

The harrowing experience of women who bear the brunt of the brutal war on drugs during the previous administration of Rodrigo Duterte surely belong to these urgent issues that even until now must still be surfaced and addressed.

(Mary Ann Manahan is a feminist activist researcher and doctoral assistant at the Conflict Research Group of the Department of Conflict and Development Studies in Ghent University, Belgium. Jean Enriquez and Janica Rosales are the Executive Director and Education Officer of the Coalition Against Trafficking in Women – Asia Pacific (CATW-AP), respectively. They are also board of advisers members of survivors groups Empowered Women Survivors Collective and Bagong Kamalayan. This is an excerpt from a study entitled, “Struggling Women in the Face of Tokhang: A Feminist Action Research on the Women Victim-Survivors in Duterte’s Drug War in Bulacan,” which is part of the research project, “Violence, Human Rights, and Democracy in the Philippines.” The research project was a joint undertaking of the Third World Studies Center of the University of the Philippines Diliman and the Department of Conflict and Development Studies of Ghent University.)