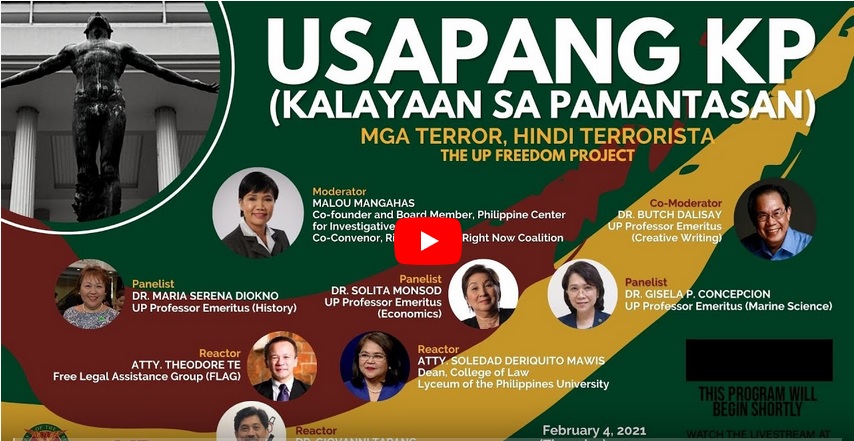

UP alumni discuss the definition of academic freedom and ways to defend it during the Usapang Kalayaan sa Pamantasan webinar last Thursday, Feb. 4. Screengrab by Enrico Berdos. From top left : journalist Malou Mangahas, UP professor emeriti Jose “Butch” Dalisay Jr. and Solita “Winnie” Monsod, UP College of Science Dean Giovanni Tapang, lawyer Theodore Te, UP professor emeritus Gisela Concepcion, and Lyceum College of Law Dean Ma. Soledad Deriquito-Mawis.

By “living like a UP student,” graduates of the University of the Philippines can help defend academic freedom from a threat of military interference, a group of alumni agreed during an online forum on Thursday.

For Creative Writing professor emeritus Butch Dalisay, the best way to defend academic freedom is to “use it, wherever you may be in this world.”

College of Law professor Theodore Te said UP graduates should live by their alma mater’s motto of “honor and excellence” as well as “bravery and valor.”

Dalisay and Te spoke at a virtual forum titled “Usapang KP (Kalayaan sa Pamantasan): Mga Terror, Hindi Terrorista” along with Economics professor Solita Monsod, Science professor Giovanni Tapang, and Soleda Deriquito Mawis, dean of the College of Law, Lyceum of the Philippines.

The UP community has been conducting protest activities against the unilateral abrogation of the 1989 agreement between the university and the Department of National Defense (DND) that prevented state forces from entering UP campuses without prior coordination and the subsequent red-tagging of 28 alumni as “dead or captured” members of the New People’s Army (NPA).

The forum – organized by the UP System, UP Office of the Vice President for Public Affairs, UP System Alumni Relations Office, UP Information Technology Development Center, TVUP, and UP Alumni Freedom Project – featured UP alumni from different sectors and voices from another university to “reflect on academic freedom as an integral element for an environment that nurtures excellence and innovation.”

“The university lives in you. You do not have to be in UP to exercise the spirit of academic freedom,” Dalisay said.

Te, former spokesperson of the Supreme Court and an active member of the Free Legal Assistance Group (FLAG), said UP graduates should apply the “tools, skills, attitudes, disposition, and critical thinking” learned from studying in UP in fighting the different “wars” that threaten academic freedom.

Monsod, a former director general of the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA), recalled the 1950s anti-communism era in the United States where professors were afraid of defending colleagues for fears of being red-tagged. This time, she said, the best thing to do is to “communicate your discomfort” in any media possible.

“This is gonna be a communications battle. This early, we have to say, ‘you are wrong, you are destroying my alma mater.’ Whatever you have to say, you have to say it, and you have to shout it,” she added.

Tapang, for his part, suggested that the UP alumni participate in forums … social media to “show their support for academic freedom” and fight an apparent systematic spread of mis- and disinformation through Facebook.

“Important po na ilabas ng mga intellectuals, ng mga taga-UP, ng mga nagmamahal sa academic freedom, ‘yung kanilang posisyon at hindi pabayaan ang mga bots, ang mga trolls at ‘yung mga may pera para bumili ng espasyo sa Facebook na mamayani sa diskusyon (It’s important for intellectuals of UP, and those who love academic freedom, to voice out their position and not let the bots, trolls, and those who have the money to buy spaces on Facebook to dominate the discussion, Tapang said.

Protesting against the military’s “baseless accusations” against UP alumni, Te declared: “It’s a war on truth right now. We need to say, ‘Anong basehan mo do’n sa sinabi mong ‘yan?’ (What’s your basis for saying that?) It’s a war on accountability: if we are in a capacity to hold people accountable administratively, legally, for untruths in the public sphere, then we should do that.”

“It’s a war on excellence. Arguments that are mediocre are being bandied around as truth. It’s also a war on honor: there’s so much lack of integrity that’s going around,” he added.

Deriquito-Mawis called on the UP alumni to defend academic freedom by “thinking, acting and living like a UP student.”

“Be aware of what is happening. Know the facts. Analyze. Make a stand. Love the truth. That is the tatak ng (brand of) UP. We honor not only excellence but integrity when we honor the truth,” she said.

What is academic freedom?

Quoting UP Diliman Chancellor Fidel Nemenzo’s 2020 vision paper, Monsod defined academic freedom as “the freedom to challenge orthodoxies and established ways of thinking and acting without fear of repression or punitive action.”

Te noted that academic freedom is both enshrined in Article XIV, Section 5 [2] of the 1987 Philippine Constitution and the UP Charter (R.A. No. 9500).

The lawyer then explained that the Supreme Court interpreted the Constitution’s definition of academic freedom in the 1989 case UP v. Ayson by citing this concurring opinion of Justice Felix Frankfurter in the 1957 American landmark case Sweezy v. New Hampshire:

“… [The school or college] decides for itself its aims and objectives and how best to attain them. It is free from outside coercion or interference save possibly when the overriding public welfare calls for some restraint.”

Academic freedom allows a university to determine what can be taught, who can teach, and who should be able to study. It allows faculty staff to research their topics of interest without censorship, and to teach in a manner they deem professional. Students can study what they want and express their own opinions, Monsod elaborated.

But there are limits, Monsod warned. The university’s “responsibility” in its practice, as defined in the UP Charter, means that students and faculty members are not exempted from the disciplinary sanctions from violating campus regulations, professional conduct, and the law.

Violations of academic freedom

Dalisay recalled how students and faculty could not practice academic freedom due to arrests in the Martial Law era.

“Military men were entering the Faculty Center. They were dragging people out and arresting people right and left. You could not enter the campus without the bus stopping for soldiers to search who among the passengers were insurrectionists,” Dalisay said in a mix of English of Filipino.

Recent academic freedom violations include cases like UP scientists being called “paid hacks,” the military’s allusions of an existing shabu lab in the campus, and threats on field workers accused of being New People’s Army members, according Tapang.

Letting these issues persist would lead to the loss of academic freedom which would stop the production of new knowledge, he argued.

“At kung wala ‘yung ganoong freedom para magtanong ka, nawawala yung … function ng university na maghanap ng bago, maghanap ng maganda, at gumawa ng iba’t ibang mga bagay na makakatulong sa lipunan (And if there’s none of that freedom for inquiry, we lose the … university’s function to find new and beautiful things, and to make different things that will help society).” he said.