Water has always defined Manila’s existence.

Metro Manila is crisscrossed with a wide network of rivers, canals, creeks, and estuaries or esteros described as “modified systems of natural channels and brackish waters from coastal lakes,” and used historically as a flood and storm drainage system as well as transportation and sewerage system.

Geography and flooding

Manila’s frequent flooding is interconnected with its geography: 1) Manila is less than two meters above sea level; and 2) the presence of numerous bodies of water and inland estuaries that run through the various areas of the metropolis.

Metro Manila lies on one of the widest floodplains in the country between Manila Bay on the west that opens to the South China Sea, and Laguna de Bay on the southeast, a large and shallow lake.

The 25.2-kilometer Pasig River connects Marikina River and Laguna de Bay to the South China Sea and smaller rivers from nearby provinces. In Tagalog, “pasig” means “a river that flows into the sea.”

Vanished waterways

L.Q. Liongson in his paper, The Esteros of Manila: Urban Drainage a Century Since (2000), describes esteros as “an estuarial network of narrow tidal creeks defining the Pasig River delta.” The San Juan River and the esteros of Binondo, Quiapo, and San Miguel are “the principal waterways” on the north bank of the Pasig River; the Estero de Pandacan is “the only significant tributary” from the south bank.

He noted that other waterways drain directly into the Manila Bay such as the Estero de Vitas in the north and the Estero Tripa Gallina which joins the Parañaque River in the south. The esteros used to be interconnected and reached the river estuaries of Bulacan and Pampanga.

In 1903, there were “over thirty esteros or branches of esteros within the city limit, notes Liongoren and pointed out that an inland lagoon connected with the Tondo tributary of the Estero de Binondo in an 1898 map had disappeared in 1987 maps, replaced by the Tutuban railyards of the Philippine National Railways.

The upstream branches of the Estero de San Miguel that used to drain the UST campus and other parts of Sampaloc have also disappeared. To this day, the area is known for developing flash floods amidst sudden downpours.

Metro Manila has around 237 esteros says the Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

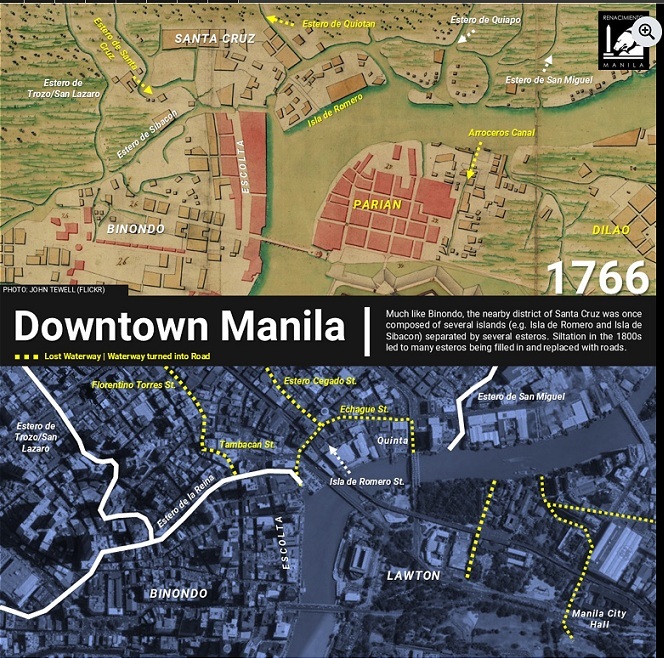

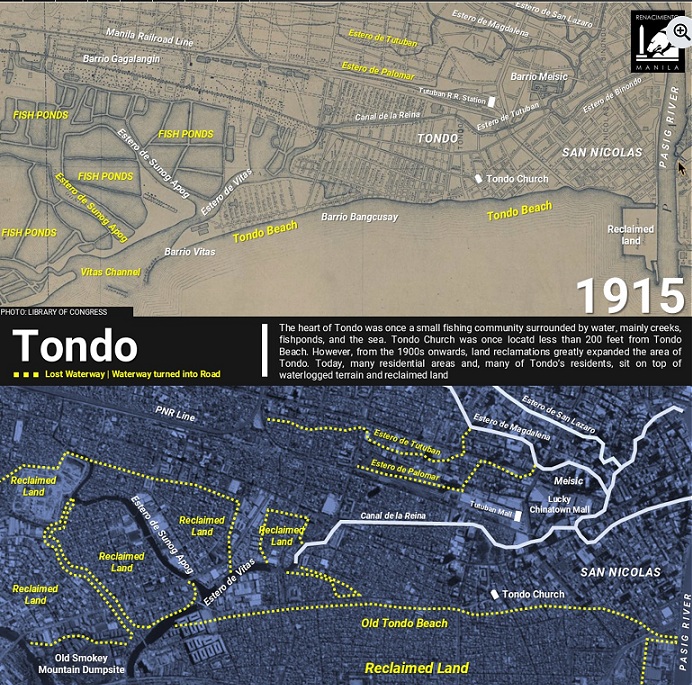

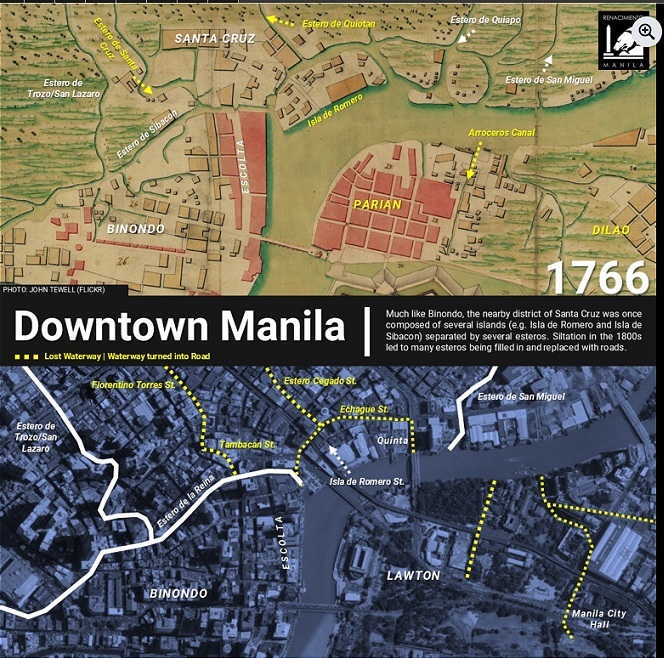

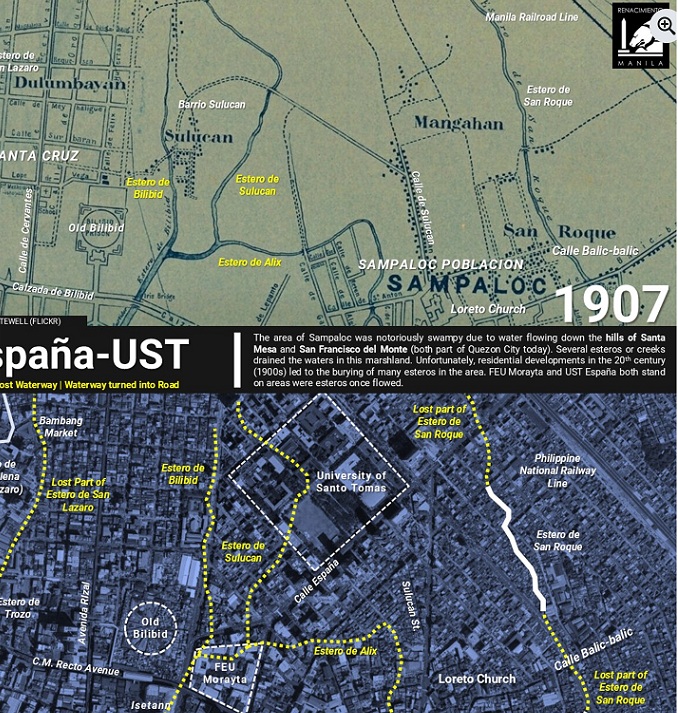

A recent Renacimiento Manila post by Diego Torres revisits several areas in Manila where waterways have disappeared by comparing maps of 1766, 1894, 1907, and 1915 with current satellite imagery.

Intramuros: Part of today’s Intramuros used to be uninhabited swamplands. Many natural and man-made waterways surrounded the Walled City, including a double moat that protected it from floodwaters. By the 1900s the double moats were filled in and became a sunken garden and parks; poor landscaping for a golf course in the 1980s led to floodwaters returning to Intramuros.

Tondo: one of the earliest fishing settlements, reclamations since the 1900s increased its land area. Tondo residents today live on top of reclaimed land. Tondo Church used to be less than 61 meters from Tondo Beach. Canal de la Reina is a major man-made waterway that cuts into the center of Tondo, to connect Estero de Vitas to Binondo. It used to be a busy waterway that brought goods from Malabon and Navotas to Manila.

Quiapo: A network of esteros existed between swampy Quiapo where the church now stands, and the areas of San Sebastian and San Miguel. Most of these esteros are gone, built over with residences, schools, and commercial buildings in the early 20th century.

The FEU campus, with its oldest building the Nicanor Reyes Hall completed in 1939, Isetan Mall in 1988, and the San Sebastian Residences in 1925, a 20-story building for Manila’s urban poor, stand on these esteros today.

España-UST: Sampaloc is another swampy place, due to waters flowing from the hills of Santa Mesa and San Francisco del Monte, both part of Quezon City now. Creeks and esteros drained the waters in the area, such as the esteros of Solucan, Bilibid, and Alix, near UST and FEU. Urbanization and building construction since the early 20th century have buried many esteros in the area.

Ermita-Malate: Both areas used to be very near the shores of Manila Bay with Ermita Church as its center and became seaside communities dotted with huge mansions built by Manila’s wealthy families.

Slowly the sea and the beach have become further away, lost with the construction of wide boulevards called Cavite Boulevard in the 1910s, today’s Roxas Boulevard. The area parallel to Taft Avenue was an estero buried in the 1910s, with the area called “Ynundacion” or flood prone.

Today, floods regularly occur at the intersections of Taft Avenue and UN Avenue, and the streets of General Luna and Padre Faura.

Numerous factors contribute to flooding in Metro Manila, mostly related to human activities: population increase, urbanization, silting of riverbeds and canals, clogging of waterways by garbage, plastic pollution, draining and filling in of waterways that result in fewer water channels, deforestration, migration, land subsidence, groundwater extraction, and coastal land reclamation

Amidst billions of pesos spent in flood-control projects, floods will persist