Text and photos by ELIZABETH LOLARGA

Archive photos courtesy of the MANILA SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

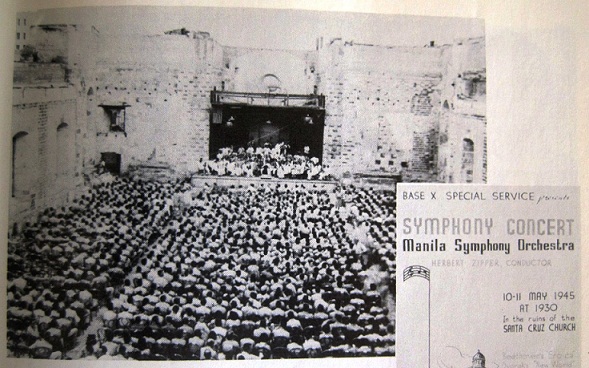

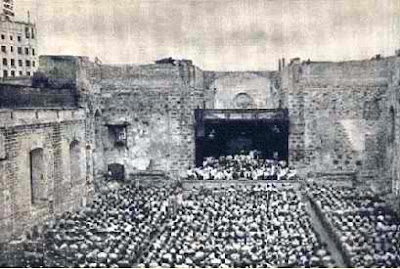

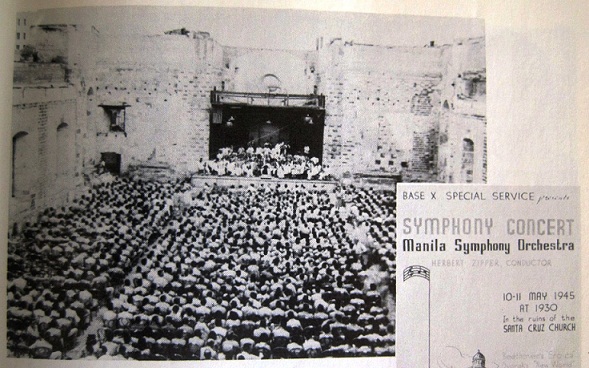

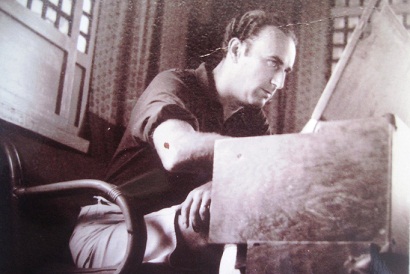

The musicians who heeded the call of conductor Herbert Zipper to join the Manila Symphony Orchestra’s first concert after the Liberation of Manila in 1945 came from different parts of the country that had seen four years of hell.

Some emerged from the dungeons of imprisonment at Fort Santiago, others from the University of Santo Tomas internment camp. A few arrived in time for the first rehearsals in tattered clothes, unrecognizable from being burnt by the sun and ravaged by hunger—they had been guerrillas.

Still there were those who did not show up at all like Ernesto Vallejo, the concertmaster. He and his family were massacred by the enemy in Tanauan, Batangas. Other fighting musicians perished during the long Bataan March.

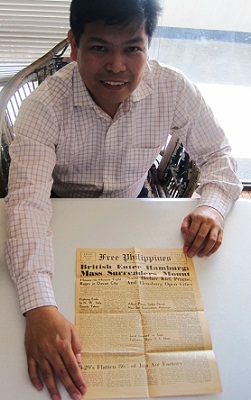

Jeffrey Solares, MSO associate conductor and executive director, gets goose bumps on his arms whenever he goes over the orchestra’s archives. These include yellowing programs, black and white pictures of musicians from the 1940s, a typewritten copy of the speech Mrs. Trinidad Legarda, head of the Manila Symphony Society, read during the first MSO concert in the ruins of Sta. Cruz Church in May 1945 when the war had ended. These will be turned over to the Ortigas Foundation Library for digitizing, preserving and safekeeping.

On March 13, the MSO will reprise the same 1945 program in “Music of Peace” that commemorates the 70th anniversary of the Liberation of Manila at 7 p.m. at Meralco Theater, Ortigas Ave., Pasig City: Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 in E Major or the “Eroica”, and Dvorak’s Symphony No. 5, Opus 95 in E Minor, also called “The New World Symphony.”

Solares recounted how Zipper vowed that he would play the heroic “Eroica” once the Nazis and their allies were defeated. The Austrian musician had earlier been imprisoned in Dachau but managed to escape. His fiancée, the ballerina Trudl Dubsky, one of the European Jews allowed into the Philippines when they sought asylum from the Nazis during the Manuel Quezon regime, arranged so he could follow her here. They married in Roman Catholic rites.

Ironically, Zipper was arrested by the Japanese and imprisoned at the then University of the Philippines Conservatory of Music in Manila where he continued working for the resistance. Solares said, “The Japanese tried to revive the MSO to show a semblance of normalcy, but the Legarda family who ran it didn’t cooperate and gave all sorts of excuses.”

The Legardas, however, did not lose their passion for music during the Japanese Occupation. But they hid the precious music pieces in a dry wine vat in their distillery until it was time to bring them out. These surviving scores are still used by MSO musicians as references. Solares quipped, “Maybe that’s why musicians like to drink.”

Benito Legarda Jr. recounted how Dr. Zipper organized a “secret concert” on the eve of Dec. 24, 1944, to surprise Filomena Legarda, the founding president of Manila Symphony Society, on her birthday. Solares said four members of the Legarda clan were the soloists for the Bach-Vivaldi concerto for four pianos. The concert was done in their home and entailed enormous challenges not the least was the need to bring four pianos in their living room secretly in the midst of a war.”

Solares said the Legardas continued to support the orchestra right after the war “until the early ’70s when they were booted out of the Manila Symphony Society upon its transfer of administration to the Metropolitan Theater. However, at present the Legardas have renewed their support to the present MSO by sponsoring the salaries of four principal orchestra members.”

Last year he received the MSO memorabilia of Sgt. Earl Smith (ret.) that Solares thought would be perfect for a historical exhibition. He mailed sepia-toned photos, too, but after sometime he didn’t reply to Solares’s emails. Meanwhile, MSO board trustee John Silva suggested a concert to mark Manila’s liberation, volunteering to find a sponsor for it.

Legarda Jr. was able to trace some surviving people who were in that Sta. Cruz Church audience and is still trying to track down the whereabouts of some musicians. Solares reported, “We finally found a surviving Filipino musician who played in the historic 1945 concert. She is Mrs Pilar Benavides Estrada, a violinist. She is now 85 and will attend tonight’s concert.”

Smith also read about the MSO activities in the Internet and contacted Solares. After violinist Oscar Yatco died last year, Smith and Mrs. Benavides are possibly the only ones left from that historic concert.

The American soldiers and pilots under Gen. Douglas MacArthur were perplexed when they saw what was in the list of priority supplies to be flown in ASAP from the mainland US. Zipper and MacArthur were pals. On the approved list were strings for violin and other string instruments; these were labelled as “precious cargo” along with weapons and medical supplies.

William J. Dunn, a war correspondent who was present in the 1945 concert, wrote that the Eroica had been performed by many greater orchestras “but never with greater feeling than I have heard,” and those orchestras produced “far fewer moist eyes.”

Zipper chose the Dvorak symphony because it carried themes from native Americans and it was a gratitude piece for the help of the US.