By ALLAN YVES BRIONES, BRYAN EZRA GONZALES and ARIANNE CHRISTIAN TAPAO

Photos by LUIS LIWANAG

Infographics by ARIANNE CHRISTIAN TAPAO

[metaslider id=35140]

WHEELCHAIR ramps have sprouted a stone’s throw away from the food hubs and nightlife scene of Timog Avenue.

These recently constructed ramps pepper Scout Tobias, a street that cuts across several residential roads in Barangay Laging Handa in Quezon City (QC).

At first glance, this seems to be in consonance with Quezon City’s vision to be a haven for persons with disabilities by 2018.

Last year, the city boasted around 16,000 registered as PWDs, a portion of whom have mobility disability.

Upon closer look however, these ramps are nothing more than decorations or props as they do not serve the purpose for which they were constructed: inclusive mobility.

These ramps are rendered unusable due to poor planning, outdated ramp design and flawed placement.

Ramps either end abruptly into a wall, into a tree or there are no spaces around to let persons on wheelchairs maneuver back to the sidewalk without obstructions.

“Who would use that? It’s an insult to PWDs,” National Council on Disability Affairs (NCDA) communications chief Rizalio Sanchez said in Filipino upon seeing photos of the ramps.

NCDA planning head Araceli de Leon said the existence of PWD ramps does not always equate to accessibility.

A sidewalk with a ramp “is just as useless” as without one, she said, if there is an obstruction like a wall, garbage can, or street post blocking the way.

“Beyond access,” de Leon said, “it’s a violation of the (accessibility) law.”

In the QC branch of the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), planners admitted that the ramp design used for the area was outdated.

“The standard (ramp) was the first design, that’s why it was implemented [in Scout Tobias],” said project inspector Chris Ramirez. “But if it were me, it should be (two-directional ramp).”

He added that only when there is a road widening does the integration of ramps come.

Aside from an outdated planning, the framework approved by the department is not being implemented properly, as electrical posts become a barrier for the making of these ramps.

DPWH-QC had talks with the Manila Electric Company on the relocation of the electric posts, engineer Art Gonzales, DPWH-QC planning head, said.

“Kaso ang nangyayari, ang nare-relocate lang is ‘yung mismong nasa carriageway ‘yun sa roadway (But what’s happening is only those posts in carriageways are relocated),” he said, referring to posts on the sidewalk which are yet to be removed and where the ramps should be placed.

Everywhere you go in the city, posts stand between the ramps and the space for PWDs to maneuver in, he said.

QC PWD Affairs Office (QC-PDAO) focal person Arnold de Guzman said ramps should have adequate landings so PWDs can rest and maneuver themselves after climbing the slope.

“The rest should be enough to accommodate a wheelchair,” he said. “But a lot of ramps don’t have rests because some are not sensitive in constructing ramps.”

In another instance, he said he once received a report about a student with disability who was sideswiped by a speeding car along E. Rodriguez Street in QC. Barriers had rendered the sidewalk impassable for PWDs and the student opted to use the road instead.

“Instead of having passable sidewalks, we have barriers like these” he said. “They are forced to pass through road itself, which endangers the PWDs.”

Sanchez said this is why ramps should not be placed just anywhere.

“Kapag nakakita ka ng ganyan, dapat (When you see that, it should be) anywhere you facilities should be accessible to all users with disabilities,” he said.

These barriers run counter to the country’s accessibility law.

Signed in 1983, Batas Pambansa Bilang 344 guarantees PWDs full participation in society development by requiring buildings, institutions, establishments and public utilities to install facilities and other devices “such as sidewalks, ramps, railings and the like.”

In 2009, a DPWH Department Order laid down the measurements and design that the ramps should follow.

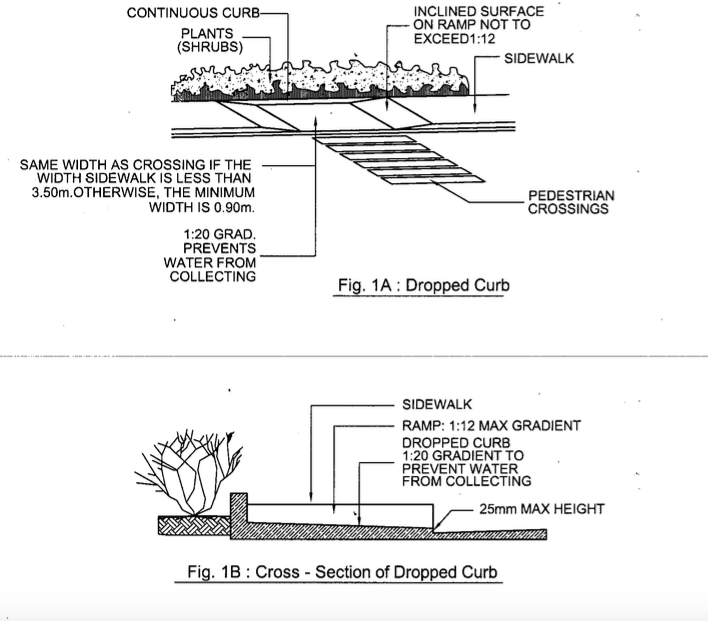

A dropped curb ramp. Screencap from 2009 Department Order 37

The dropped curb ramps, or two-dimensional ramps as Ramirez mentioned, should be provided on pedestrian crossings or in between ends of footpaths of streets or roads.

To prevent water from collecting at the sidewalk, the ramp entryway should be sloped toward the road with a 1:20 maximum gradient, or no more than a 2.86 degree angle. Its width should correspond to the sidewalk crossing, according to the order, with the minimum at 0.90 meters.

But the DPWH-QC’s plan to install the dropped curb ramps in appropriate areas was only proposed to the Central Office last year, Ramirez said.

Sanchez, who is in charge of monitoring and evaluating projects for PWDs, said the sad state of unusable ramps extends to other cities in Metro Manila.

This is a form of discrimination to PWDs, he said.

“Parang hindi mo binibigyang halaga yung tao (You’re not giving significance to them),” he added.

Meanwhile, de Leon urges the local government to take stock of the current state of PWD accessibility in their city.

Accessibility for the PWD means accessibility for all, she said. “If the public streets and sidewalks are properly designed, then no one is really disabled.”

(The authors are University of the Philippines students writing for VERA Files as part of their internship. July 17-23 is the 38th National Disability Prevention and Rehabilitation Week.)