Repressive approaches to drug use that inflict harm on vulnerable persons and communities instead of upholding dignity and human rights continue to rule global drug control policies, said a new report by a global drug policy advocacy organization.

“International drug control is failing as the war on drugs is gaining momentum,” said the International Drug Policy Consortium (IDPC) in its report, “The UNGASS decade in review: Gaps, achievements and paths for reform,” which assessed the progress made since 2016 when the UN General Assembly Special Session or UNGASS held a special session on the world drug problem.

“The system remains dangerously misaligned with the UN’s commitments to human rights, public health, sustainable development and multilateral cooperation — wasting billions in public funds while inflicting serious harm on some of the world’s most vulnerable communities,” declared the report.

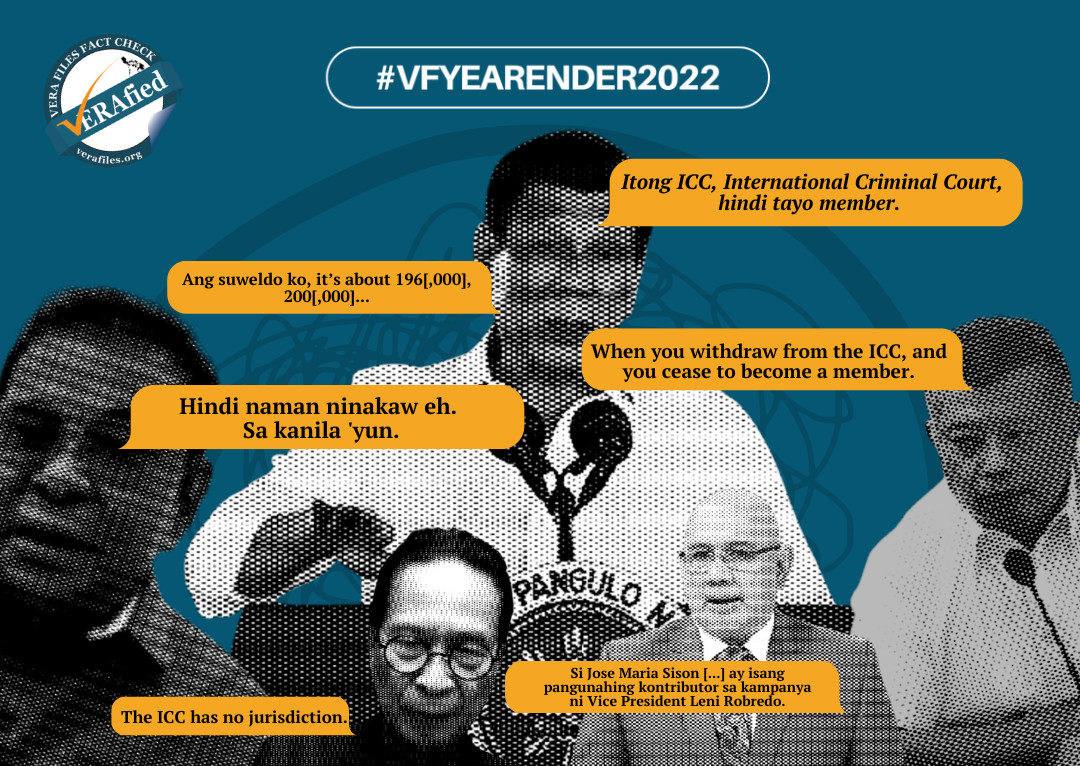

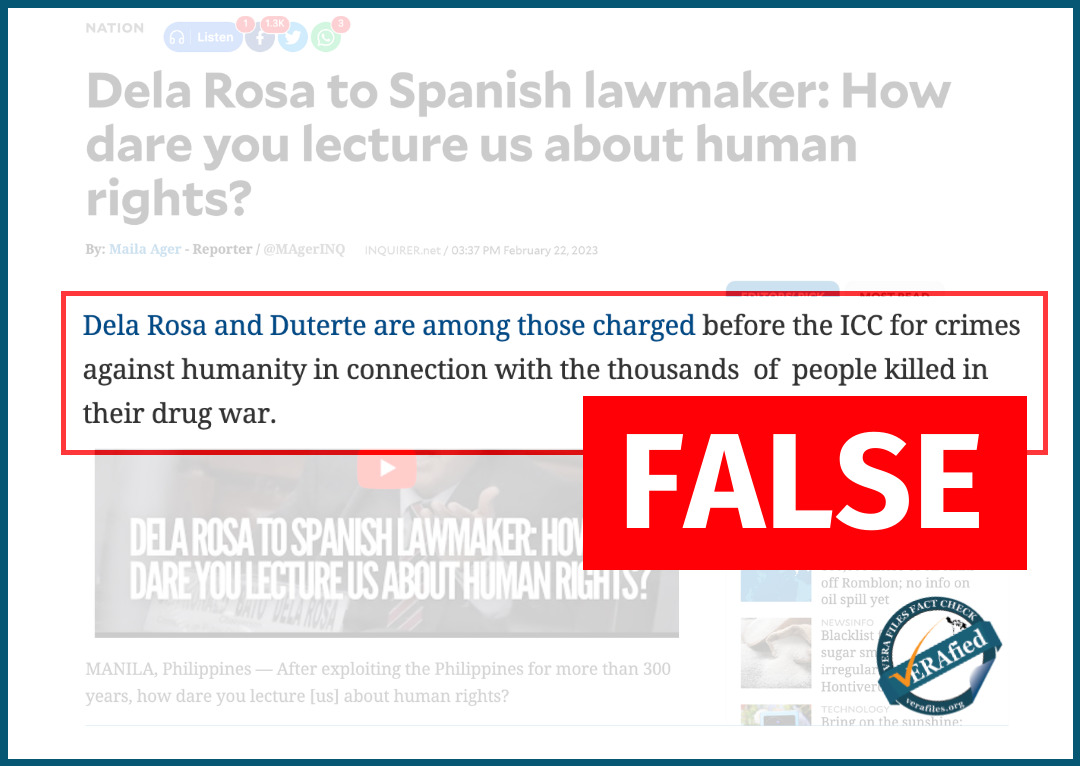

The IDPC cited the anti-drug campaign of former president Rodrigo Duterte, who is now at the International Criminal Court (ICC) facing ‘crimes against humanity’ charges as a indirect co-perpetrator of the killings while serving as Davao City mayor and during his presidency.

Protesters marched to the Batasan Pambansa in 2021 where Duterte delivered his last State of the Nation Address. Photo by Luis Liwanag.Protesters marched to the Batasan Pambansa in 2021 where Duterte delivered his last State of the Nation Address.

The IDPC, which has offices in London, Amsterdam, Accra, and Bangkok, is an international network of nongovernment organizations (NGOs) advocating for human rights-centered drug policies and is a member of the Vienna NGO Committee on Drugs and the New York NGO Committee on Drugs that coordinates civil society inputs into official processes such as the UN.

The 2016 UNGASS on drugs, considered a watershed moment in global drug policy, unanimously adopted the “Outcome Document” prepared by the UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs containing 100 recommendations on demand and supply reduction, controlled substances for medical and scientific purposes, human rights, challenges and new trends and international cooperation.

The historic 2016 moment created a chance to reconsider the prevailing global concept on drugs and to chart a new direction but 10 years later, the IDPC report said governments failed to deliver on the promise to move towards a more humane and evidence-based approach to drugs.

Juan Manuel Santos, who led the 2016 UNGASS to address the world drug problem, said in the report’s foreword: “Across the world, people affected by drug policies – including people who use drugs, small scale farmers, Indigenous peoples and other marginalized communities – continue to face stigma, criminalization, violence and exclusion.”

“Criminalization and militarized strategies have utterly failed. They only shift the harms elsewhere, enriching criminal networks while harming our communities, our environment, and our hope for peace,” said Santos, a 2016 Nobel Peace Prize winner and former president of Colombia, a country that has always been deeply meshed with its own “war on drugs.”

“This report exposes how far we still have to go — and points to the way forward. It is time to overhaul the way the world approaches drugs, putting lives, communities, and human rights at the center,” he said.

‘Global drug situation more complex, deadly’

Drawing on UN data, academic research, civil society contributions and a survey among IDPC members and partners, the report said there have been reforms in a number of countries, but punitive and prohibitionist approaches continue to dominate global drug control, at enormous human and financial cost.

“Far from curbing drug markets, these policies have contributed to their staggering expansion and diversification, while the number of people who use drugs is estimated at 316 million worldwide – a 28% increase since 2016,” the report noted.

It said repressive policies drive harms that can be prevented, and noted the following:

- 6 million drug use-related deaths between 2016 and 2021, with projections indicating further sharp increases

- One in five people globally incarcerated for a drug offense, fueling mass incarceration and disproportionately affecting marginalized communities

- Over 150 countries reporting inadequate access to opioid pain relief due to overly restrictive controls on essential medicines

- The expanding use of the death penalty for drug offences, resulting in hundreds of confirmed executions, with many more hidden from official public records

- The displacement of illegal drug activities into remote and environmentally fragile regions, including Central America and the Amazon basin, as a result of interdiction and eradication efforts.

Ann Fordham, IDPC executive director, said, “At a time when multilateralism is under strain, drug policy stands out as one of the UN’s most glaring failures” as punitive approaches are costing lives, undermining human rights and wasting public resources, while silencing the very communities that hold the solutions.

“This report shows why governments must move beyond rhetoric and commit to real structural reform,” she added.

The report cited the Philippines and Singapore as two countries that sought to “place a drug-free ideology in their official national identity,” a framing that justified extremely harsh responses as part of a struggle for survival – and has generated imitators across the region.

Since 2016, the report noted the rise of authoritarian politics and governments such as in Italy, Hungary, the Netherlands and Slovakia in Europe, Argentina in Latin America, the Philippines in Asia, and the USA, resulting in increased limitations on drug policy reform, including travel and free speech restrictions, arbitrary inspections and surveillance, unclear registration processes, restrictive funding approvals and harassment of advocates.

“From 2016 to 2025, several countries launched national anti-drug campaigns that resulted in the killing of hundreds of people suspected of using drugs or of being involved in other drug-related activities.”

“The most notorious example is the national anti-drug campaign in the Philippines, which began in June 2016 at the explicit instructions of then President Rodrigo Duterte, immediately upon his taking office,” the report stated.

“Four years later, the OHCHR (Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights) set the conservative estimate for the number of killings at 8,663, whilst noting that some estimates were three times higher. The use of lethal force has continued to be a hallmark of drug policing in the Philippines beyond the Duterte administration.”

It also cited the Dahas Project, a research-led group of the University of the Philippines Third World Studies, which recorded 342 drug-related killings from July 1, 2023 to June 30, 2024, under the incumbent government of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.

The report said Marcos and several high-level politicians and police officials have admitted that abuses were committed, but by June 2024, only 52 cases had been investigated, with only one conviction.

‘Shift focus from punishment to public health’

Duterte, now detained at the ICC’s Scheveningen Prison at The Hague in the Netherlands, is scheduled for a confirmation hearing starting on February 23 to determine if there is sufficient evidence for his cases of ‘crimes against humanity’ to move towards a trial.

In the report, Johann Nadela, executive director of the Cebu-based IDUCARE Philippines, an advocacy organization of former persons who used drugs, said that from 2016 to 2019, the ICC estimated between 12,000 and 30,000 people killed or disappeared during Duterte’s drug war, and more continue to be murdered to this day.

”As a Filipino and an advocate for rights of people who use drugs, it has been disheartening to witness the erosion of human rights and rule of law in my country,” he said. “We’ve seen countless lives lost, with many innocent people caught in the crossfire simply for the crime of using or being associated with drugs.”

“To protect human rights in the Philippines and around the world, there is an urgent need to change the way we approach drug control,” Nadela said.

“My recommendation for the UN is to advocate for the decriminalization of drug use, promote harm reduction strategies, and shift the focus of drug control from punishment to public health.”

Lawyer Ansheline Mae Bacudio, human rights manager of Initiatives for Dialogue and Empowerment through Alternative Legal Services (IDEALS), an alternative lawyers’ group, shared Nadela’s insights on presenting health-based approaches as a viable alternative, emphasizing adherence to the rule of law and human rights norms and tangible results in crime reduction and increased community safety.

”The proceedings before the ICC against Duterte are a welcome step towards accountability that gives hope for a full picture of what happened during his so-called war on drugs once trial starts,” Bacudio said.

“The eradication of drugs from street-level circulation became the excuse used to short-circuit established due process norms, and flaunt the rule of law,” she explained. “‘Drug use’ was used as a reason to dehumanize thousands, and justify their mass incarceration, or worse, their mass murder.”