Faith. Hope. Love.

These precious values are what make people truly human, according to Scriptures.

Faith, Hope and Love are also the names of the three children, all under five years old, of digital marketer Dominic Barrios and stay-at-home mom Mitzi Barrios.

Dominic and Mitzi Barrios say R.A. 11229 could still be tweaked.

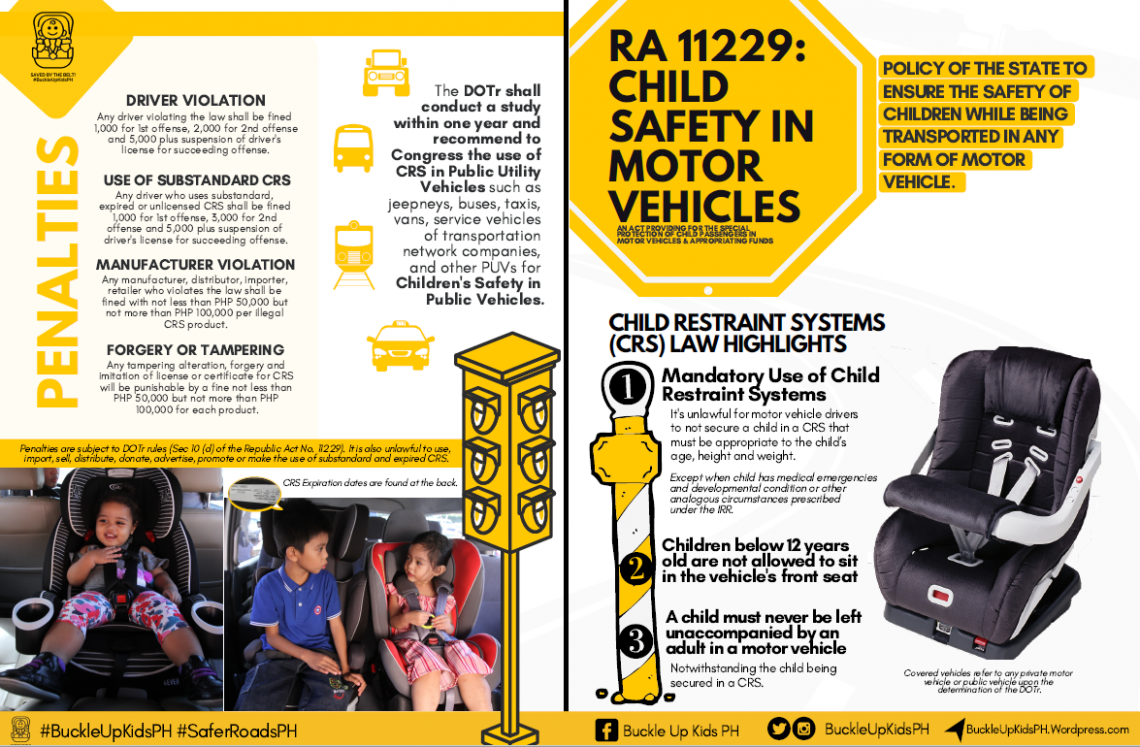

Like many responsible parents, the Barrioses want to comply with Republic Act 11229 or the Child Safety in Motor Vehicles Act, which President Rodrigo Duterte signed into law on February 22, 2019.

The law requires private-vehicle drivers to ensure that passengers who are 12 years old and younger, with heights of 4’10” and below, are secured with child restraints when riding a car. These children are not allowed to sit on the front seat of a motor vehicle.

The road safety legislation is designed to diminish the risk of injury to precious little children like Faith, Hope and Love, in the event of a collision or an abrupt deceleration of the vehicle, by limiting the mobility of their bodies.

The measure’s implementing rules and regulations are expected to be finalized this August, with the full implementation of the law expected by August 2020.

Less mobility?

However, the couple is worried over the prospect of spending a lot of money in order to comply with the law.

“Hindi kasya ang three car seats sa car (Three car seats won’t fit in the car),” Mitzi told VERA Files at a June forum of non-government organization Initiatives for Dialogue and Empowerment through Alternative Legal Services, Inc. (IDEALS) in Quezon City.

“Only two can fit, so do we need to buy a new car?” she asked in Filipino.

The Barrios family’s Mitsubishi Adventure likewise does not have the rear-seat three-point seatbelts or ISOFIX anchors needed to use the child restraints.

“The logistical problem is a big thing,” Mitzi said, as she explained that for them to be able to move around, they may need to make changes in their vehicle’s interiors and that is where costs will come in.

She expressed concern that the law could limit their mobility. There are times, she said, when the kids cannot be left at home. “If we have to go, we have to bring them or at least one or two.” With the new law, the family might have to reconsider its mobility, she added.

Protection from ‘biggest killer’

R.A. 11229 is one of the government’s responses to what the World Health Organization (WHO) called the top killer of people aged 5 to 29 years old worldwide – road crashes.

The 2018 WHO Global Status Report on Road Safety also found that four in five road-traffic deaths around the world in 2016 occurred in middle-income countries like the Philippines.

The international group said child restraints are “highly effective” in reducing injury and death to child occupants, with the greatest benefit for children under four years old.

For children 8 to 12 years old, the WHO said using booster seats reduced the risk of injury by 19 percent compared to just using a seatbelt, which is normally designed for adults.

Child car seats (L-R: Group II, Group I, Group III) from the Philippine Red Cross displayed on the table during a road safety photo exhibit last year.

The 2009 United Nations Road Safety Collaboration Manual on Seatbelts and Child Restraints lists four categories of child restraints, based on a child’s age and weight:

- Group 0 or 0+ – rear-facing, infant child seat for those aged under 1 year old, weighing less than 13 kilograms

- Group I – child safety seat for those aged 1 to 4 years old, weighing 9 to 18 kilograms

- Group II -booster seat for those aged 4 to 6 years old, weighing 15 to 25 kilograms

- Group III – backless booster seat for those aged 6 to 11 years old, weighing 22 to 36 kilograms

IDEALS advocacy lawyer Melisa Comafay discusses key points of R.A. 11229 or the “Child Restraint in Motor Vehicles Act.”

IDEALS lawyer Melisa Comafay said at the forum that her group pushed for the child-restraint law to address shortcomings in Republic Act 8750 or the “Seat Belts Use Act of 1999.”

“There is a provision in that law that says the LTO (Land Transportation Office) will come up with guidelines for the use of seatbelts for the infants, but then, this was not implemented,” she said.

“The coverage of our new law is 12 years old and below. In a way, this is a landmark law because it’s the only law that covers children while they are on the road,” Comafay added.

Incentives for compliance

Although the Barrioses understand the importance of child restraints, they said some parents may not be able to afford following the law.

“We have three children, so if you’re going to buy three car seats immediately, the cost of each car seat is from P7,000 to P12,000 so it’s a bit expensive,” Dominic said.

Atty. Karl Carumba, who helped push for R.A. 11229, says child restraints are important investments despite the cost.

Lawyer Karl Carumba, who was among the people who lobbied for the law, said at the forum that child restraints are vital investments in spite of the cost.

“If parents can spend P50,000 or more for high-end phones, then buying child restraints shouldn’t be a problem,” he said. “P5,000 could give your child a 70 to 90 percent safety advantage.”

Nonetheless, the Barrioses are hoping that the law would likewise give incentives to help parents comply more easily.

“If it’s about getting a new vehicle, and a large one is needed, would that be in the horizon for discounts?” Mitzi asked.

“I hope that they could point us to resources, where to find cheaper car seats,” Dominic added.

What about PUVs?

The parents at the forum also questioned what the government would do to keep kids safe in public-utility vehicles (PUVs).

Section 9 of R.A. 11229 states that the Department of Transportation (DOTr) must conduct a study to determine whether or not child restraints could be used in PUVs like buses, taxis, jeepneys, vans or accredited service vehicles of transport network companies.

“Should the DOTr determine, after study, that child restraint systems are not applicable in certain public utility vehicles, it shall recommend to Congress other safety measures and/or regulations for the safe and secure transportation of children in such vehicles,” the law says.

Rachel Uy says the Philippines should look at best practices abroad for how to address child safety in public-utility vehicles.

Rachel Uy, mother of one, noted that in other countries, app-based transport services like Grab can provide child restraints for passengers, albeit for selected vehicles.

Meanwhile, Mitzi noted how public transport could be an alternative for their family to get around, provided they are efficient and child-friendly.

She said if that were the case, “we won’t need to bring a car because public transport would be efficient enough to accommodate (car seats),” she said. “We need also to change the mentality that the sign of progress is if you have a car.”

“If families could only commute, I hope that PUVs would also have car seats,” Dominic said. “The burden should be on them, not on the family.”

This story was produced with the help of a grant from The Global Road Safety Partnership (GRSP), a hosted project of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC).