Images courtesy of the National Museum of the Philippines, Fernando C. Amorsolo Art Foundation, Vintana.ph, and Metrobank Foundation

Filipino painters have often painted the rural landscape in bucolic settings: a nipa hut by a stream, coconut trees and bamboo groves, carabaos and their mud baths, or the planting and harvesting rice. They have also honored the Filipino farmers in their works.

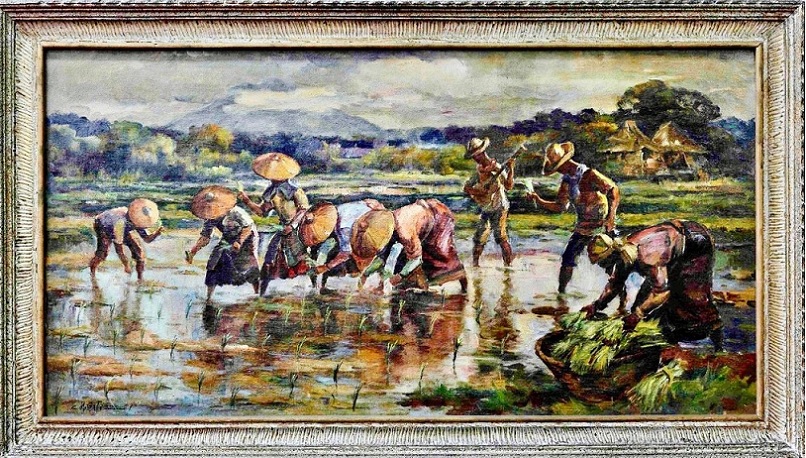

Fernando Amorsolo’s works exemplified such rustic scenes; “planting rice” has become “an iconic image” in Philippine art history. Aside from the Amorsolo School of painters, the Mabini art movement of conservatives in Ermita popularized idyllic scenes, turning out hundreds of genre paintings and landscapes reproduced in calendars, cards, advertisements, and other publications.

Contrary to the idealized rural life, planting rice has never been fun nor a joke, as a popular folk song notes.

Fernando Amorsolo (1892-1972) made a series of paintings on Planting Rice. The earliest known version is his 1921 Planting Rice: in a wet rice field, he depicts a group of women in colorful skirts or saya; a mixed group, some wearing the conical hat (salakot); and some farmers with carabaos and some planting rice. In the background, a stone church is visible. Amorsolo was the first National Artist in Visual Art proclaimed in 1972.

In art critic Alice Guillermo’s words, Amorsolo perpetuated the myth of “the beautiful land” of the new American colony. He painted hardy peasants working the green paddies, helped by rosy-cheeked and sensuous women and his technique of backlighting provided a romanticized glow to the backbreaking work of farmers.

Some early painters identified with the Mabini art movement included Miguel Galvez (Paombong, Bulacan, 1912-1989), one of the first artists who opened a shop in Ermita in 1949. Others included Gabriel Custodio (Tanza, Cavite 1912, 1993), Serafin Serna, (Raxabago, Tondo, 1919-1979), and Cesar Buenaventura (Trozo, Manila, 1919-1983).

At the opposite end of the traditionalists, Vicente S. Manansala (Macabebe, Pampanga, 1910-1981) is one of the pioneers of modernism in the country. Known for his transparent cubism, he was proclaimed National Artist in Visual Arts in1981. One of his well-known works was his IRRI mural paying homage to Filipino farmers.

Hungry Juan

Fast forward to the 2023 Metrobank Art & Design Excellence (MADE), two top awards went to young Filipinos with their works on impoverished farmers and hunger stalking the land, the true state of the nation.

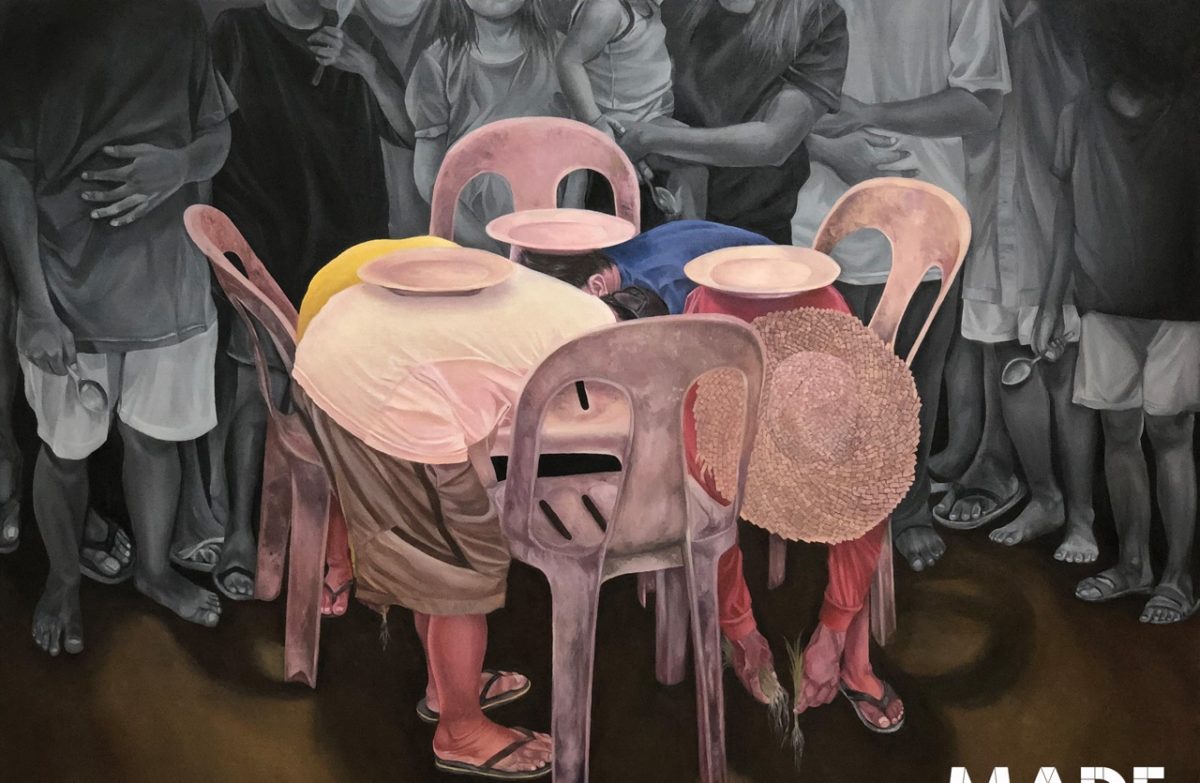

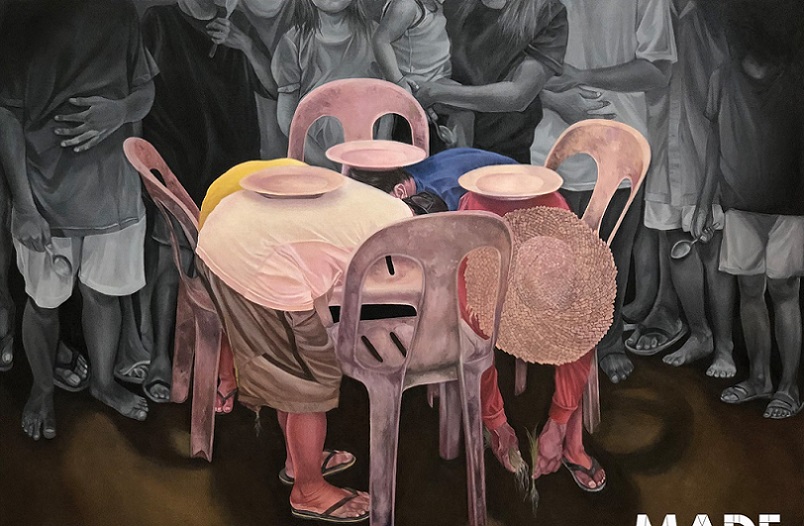

The Grand Award for oil/acrylic painting went to Jowee Ann M. Aguinaldo for Puro Kahig, Walang Matuka, 2023 (All Scratch, No Peck). Aquinaldo studied agricultural economics at the University of the Philippines, Los Baños.

Jerome Santos won the Grand Award for water media on paper, for Ha (PAG PAG) kaing Pinagkainan, 2023. Santos is a fine arts graduate of Tarlac State University and grew up in Iba, Tarlac.

Puro Kahig

“Isang kahig, isang tuka” is a Tagalog saying that literally means “one scratch, one peck,” a chicken’s action of searching for food. It refers to the precarious existence of marginalized Filipinos and their daily search for food.

Aguinaldo’s painting, Puro Kahig, Walang Matuka, depicts four farmers bent over, with their backs acting as a table with three empty plates on top. Their t-shirts are colored red, white, blue and yellow, standing for the Philippine flag. They are surrounded with a crowd with spoons in their hands, and empty stomachs.

In Aguinaldo’s words, “it is hard to think that those who feed our nation are the poorest.”

It portrays the grim plight of Filipino farmers who put food in our tables, and yet, they all go hungry and are in perennial debt. In short, they have not reaped the bounty of their hard work.

Hapag Pagpag

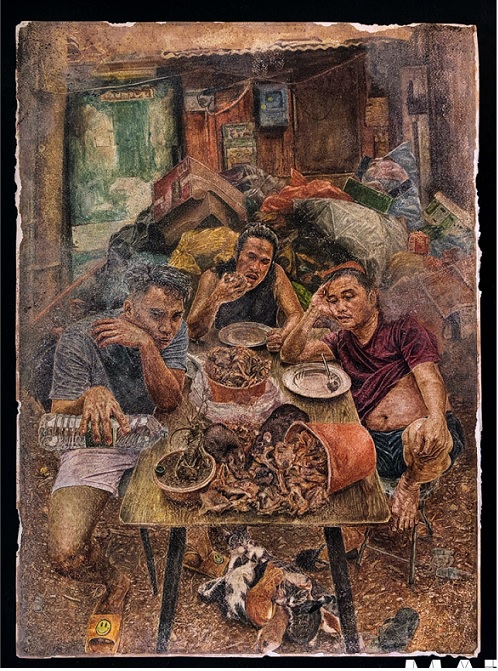

Pagpag represents the face of extreme poverty and hunger amidst overconsumption, malnutrition, and food waste, symbolized in Ha (PAG PAG) kaing Pinagkainan. It depicts three men slumped around a table laden with pagpag food, their beer bellies, all fully satiated. Until next time, when hunger strikes.

The Tagalog term pagpag refers to the act of shaking off dust or dirt; its meaning extended to food, leftover or expired, thrown into the garbage and reused and cooked into another dish, sold cheaply.

Lives at the margin

Food prices keep rising, including rice, the Filipino staple, and that promise of 20 pesos per kilo of rice remains as elusive as ever.

The hungry Filipino in statistical parlance is the number of Filipinos who experience involuntary hunger (e.g., being hungry and not having anything to eat at least once in the past three months, which grew from 9.8% in September 2023 to 12.6% in December 2023, says a Social Weather Station (SWS) survey. In the first quarter of 2024, the number of hungry Filipinos continue to rise, at 14.2%, in the latest SWS survey.

Beyond statistics, one needs to eat to survive, physically. And one does what one must do. A simple and complicated act of survival, today.