Can enforcers choose what laws to implement and when, where, how and to whom they should be applied?

The arrest of Melania Flores, a professor at the University of the Philippines (UP), last Feb. 6 has brought out a number of irregularities involving abuse of power by law enforcers.

This has to stop. People lose faith and confidence in law enforcers because of those who break the law or abuse the exercise of their authority. The late president Ramon Magsaysay said that those who have less in life should have more in law.

However, defending the rights of those who have less in life does not justify breaching the rights of others, such as in the case of the UP professor and her former house helper.

The official reason for the arrest of Flores was a warrant issued in September last year over a case involving her alleged violation of Republic Act 10361, also known as the “Kasambahay Law.” This came 10 months after the original warrant issued in November 2021 was not served, prompting the court to issue an alias warrant that was served five months later on Feb. 6.

Flores was accused of not paying the employer contributions to the Social Security System (SSS) for her helper. But the professor said the helper was no longer working for her since 2013 and that she was not aware of any complaint filed against her.

The Quezon City Police District classified Flores as its “most wanted person” because of that violation. Consequently, Judge Maria Gilda Loja-Pangilinan of Quezon City Regional Trial Court Branch 230 ordered her arrest.

The Kasambahay Law was enacted in 2013 “to protect the rights of domestic workers against abuse, harassment, violence, economic exploitation and performance of work that is hazardous to their physical and mental health.”

A 2019 joint survey by the Department of Labor and Employment (DoLE) and the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) shows poor compliance with the Kasambahay Law, from registration to the provision of benefits.

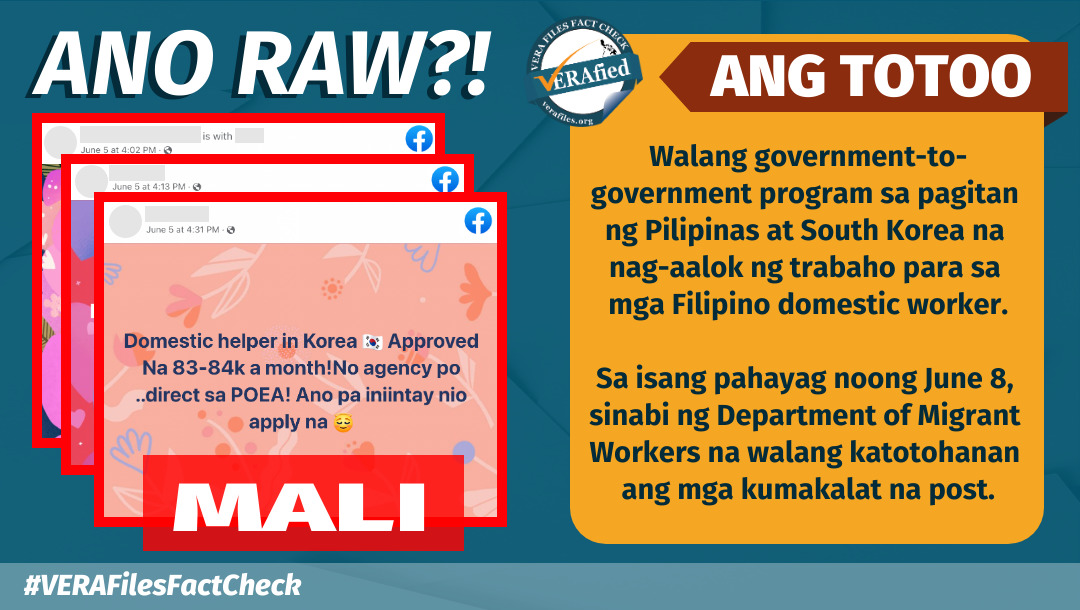

It was thus surprising that the police is finally enforcing the seemingly forgotten 10-year-old law. But how did they choose to apply it on a UP professor? To prove that Flores was not targeted because she was an activist and a former president of the All UP Academic Employees Union, the agencies tasked to implement the Kasambahay Law should relentlessly pursue employers who have been disregarding the benefits due their household helpers.

Granting that Flores violated the Kasambahay Law, which required employers to register their household help and pay the corresponding membership dues, why wasn’t she informed of the complaint filed against her? Wasn’t that a deprivation of her right to due process?

Why were the four members of the arresting team from the Criminal Investigation and Detection Group of the Philippine National Police in plain clothes, not wearing their uniforms? Worse, they introduced themselves as personnel of the Department of Social Welfare and Development giving out financial aid to gain entrance into Flores’ residence inside the UP campus in Diliman, Quezon City.

According to the Alliance of Concerned Teachers (ACT), the arresting officers showed Flores the warrant of arrest and “seized her without sufficiently explaining the nature of the case [against] her.”

Flores, a member of the faculty of Departamento ng Filipino at Panitikan ng Pilipinas (Department of Filipino and Philippine Literature), was released on the same day of her arrest, but only after posting a P72,000 bail.

The DoLE-PSA survey in 2019, seven years after the Kasambahay Law has been in effect, already identified gaps in its implementation, mainly due to the challenges posed by the constitutionally guaranteed privacy of homes. The requirement in the law for a warrant to enable DoLE inspectors to check households employing kasambahay was one of the stumbling blocks that rendered it ineffective.

How and why Flores stood out among the violators of the rights of the estimated 1.4 million Filipinos working as kasambahay is not easy to understand. Perhaps the CIDG can explain.

Another issue raised on the arrest was the 1992 agreement between UP and the Department of the Interior and Local Government which bars the entry of the PNP into the UP Diliman campus without prior notice. Why the arresting officers misrepresented themselves and posed as DSWD was a clear case of deception and a violation of this agreement.

UP signed a separate accord with the Department of National Defense in 1989, which restricts military access to campus grounds.

While the Kasambahay Law — which was considered a landmark legislation as it treats kasambahays with dignity and decent wages and other benefits — must be observed, enforcing its provisions should not disregard the basic human rights of employers.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.

This column also appeared in The Manila Times.