(Second of two parts)

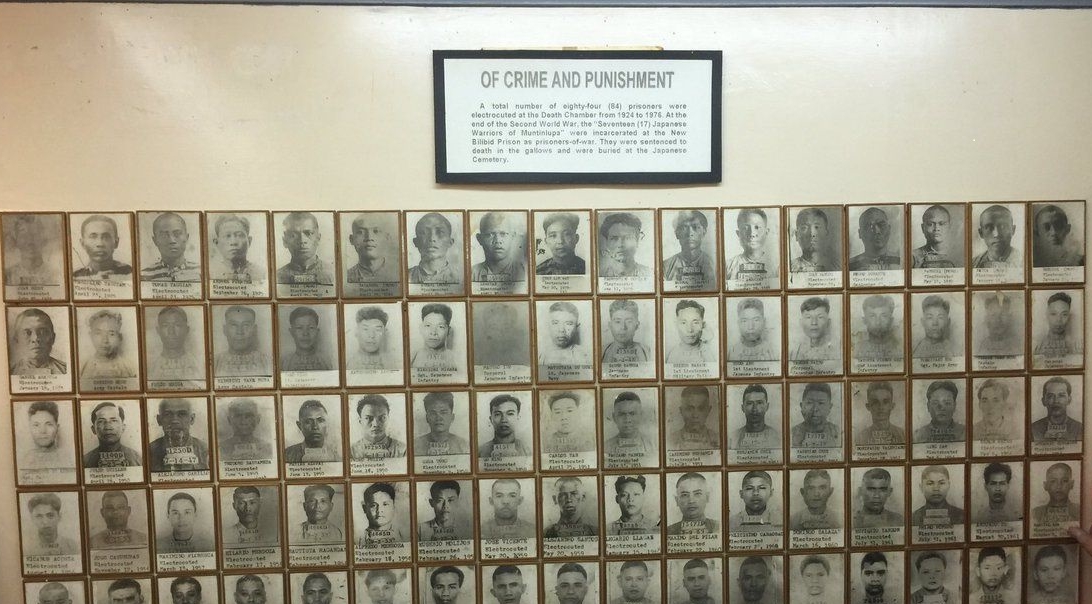

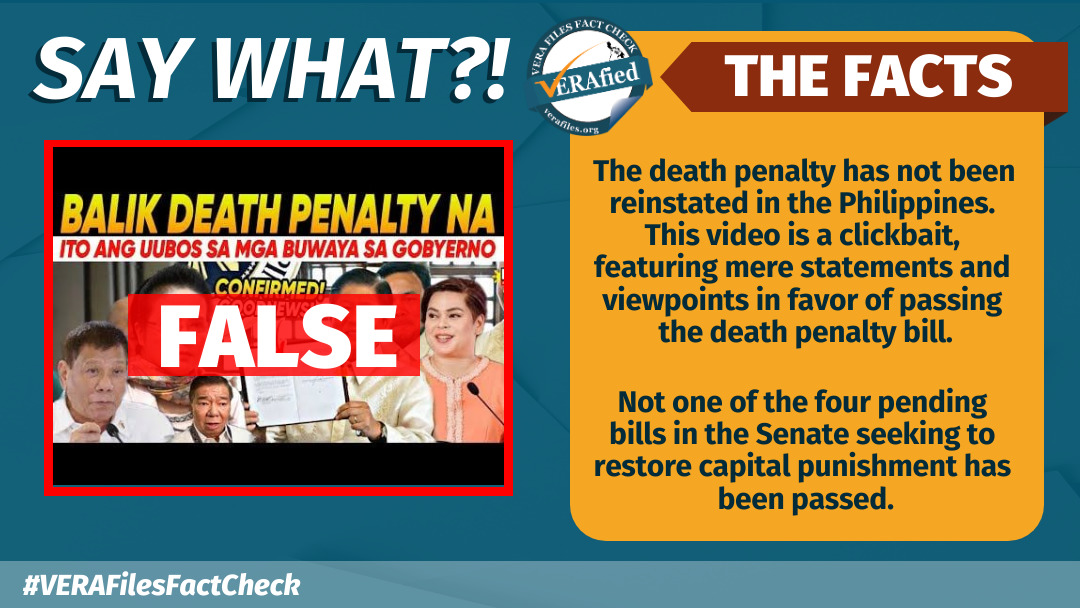

Photo gallery of the electrocuted convicts. Photo by Jamela

Alindogan.

Since the Philippines regained its independence on July 4, 1946, those who

were elected president accepted the death penalty as a matter of

course. Except for Manuel Acuña Roxas, Corazon Cojuangco Aquino, and

Ramos, all the other presidents reckoned with the fate of convicts up

for execution. The telephone in the execution chamber supposedly with

a direct line to Malacañang came to symbolize the looming power of

the president over a convict’s life. The president at the very last

minute could order a reprieve or commute a sentence.

President Elpidio Rivera Quirino (April 17, 1948-Dec. 30, 1953) had 13

men executed during his term. To two convicts he gave a 15-day and a

30-day reprieve, respectively, before finally allowing the prisons

director to proceed with the execution. To Ireneo Bongog, he first

gave a 30-day reprieve before finally commuting the sentence to life

imprisonment. Quirino was the first president to allow the execution

of foreign nationals, three Chinese who were convicted of kidnapping

and kidnapping with murder.

Under Quirino’s watch, the electric chair was first used on April 26,

1950. Julio Guillen attempted to assassinate President Roxas on March

10, 1947, by throwing a grenade at him during a rally in Plaza

Miranda. An aide managed to kick the grenade from the stage. When it

exploded in the plaza, it killed one and severely injured four

others. Quirino was Roxas’ vice president and loyal party mate.

President Ramon del Fierro Magsaysay (December 30, 1953-March 17, 1957) had six

men executed. He halted the double execution of Ging Sam and Gregorio

Gonzales on May 6, 1954, to carefully study their cases and decide

whether to grant executive clemency. The usual hour for executions

was 3:00 in the afternoon. He gave the go signal to proceed around

6:00 in the evening. The executions ended at 7:09 that night. He once

issued a 15-day reprieve simply because the execution fell on Mabini

Day (July 23, 1956). Then on August 3, 1956, Malacañang decided to

cut the reprieve short; the convict was executed the following day.

Of Maximiano Floresca, writer and editor Ileana Maramag noted in the

April 14, 1957 issue of Sunday Times Magazine: “One of the last

wishes the prisoner asked of his family was to vote for Magsaysay.

The President had earlier granted him two reprieves and for this the

condemned man had been sincerely grateful.” He did not get another

reprieve and was executed on March 14, 1957.

President Carlos Polestico Garcia (March 18, 1957-December 30, 1961) had 14 men

executed. Most of these men had received a 30-day reprieve. Some got

two or three more reprieves, but he eventually allowed their

execution. He commuted at least four death sentences to life

imprisonment. The most talked about was the one received by Primitivo

Ala. He was supposed to follow Marcial “Baby” Ama to the electric

chair on October 4, 1961, but as Ama’s body was taken out of the

death chamber, he was informed of the commutation of his sentence.

President Diosdado Pangan Macapagal (December 30, 1961-December 30, 1965) had

but one instance to review with finality the case of three men who

were up for execution the same day for the same charge of murder. On

January 30, 1962, he had two of them executed. Constantino Dueñas,

the third convict, received a sentence commutation.

President Ferdinand Edralin Marcos (December 30, 1965-February 25, 1986) had 32

convicts executed. Sixteen of them were executed after martial law

was declared. This fact, however, is being disputed by newly elected

Senator Imee Marcos. Senator Marcos insists that her dictator-father

had only one person, the Chinese drug lord Lim Seng, executed. Prison

records do not bear this out.

Daughters of former presidents tend to lower the number of convicts their

fathers had allowed to be executed. Macapagal-Arroyo was mentioned in

a June 24, 2006, report of the Philippine Center for Investigative

Journalism (PCIJ) to have claimed that her father allowed only one

execution during his term.

Marcos grappled with the issue of the death penalty. It was an important

issue for him, important enough to enlist the help of his

propagandists in the press. Here’s Vicente

Albano Pacis (Republic, March 27, 1970):

In a single stroke of the pen, President Marcos has commuted to life the

death sentences imposed by the courts on a total of 339 prisoners, 49

already confirmed by the Supreme Court and the others pending before

this body. With this action, he has also given tacit notice that no

death penalty will ever be carried out during the balance of his

term.

If only Marcos truly did that. Reporting for The Weekly Nation (June 22,

1970), Romy V. Mapile wrote that it was not a commutation but a

reprieve: “A total of 351 convicts saw a new ray of hope when

President Marcos issued a general stay of executions last Feb. 12.

The death sentence of 48 of them had been affirmed by the Supreme

Court.” And the Official Gazette itself

had this entry for Feb. 12, 1972, in the “President’s

Week in Review”: “Granted reprieves to all convicts in the

national penitentiary sentenced to die by electrocution pending

serious study by the government on the possible abolition of capital

punishment.”

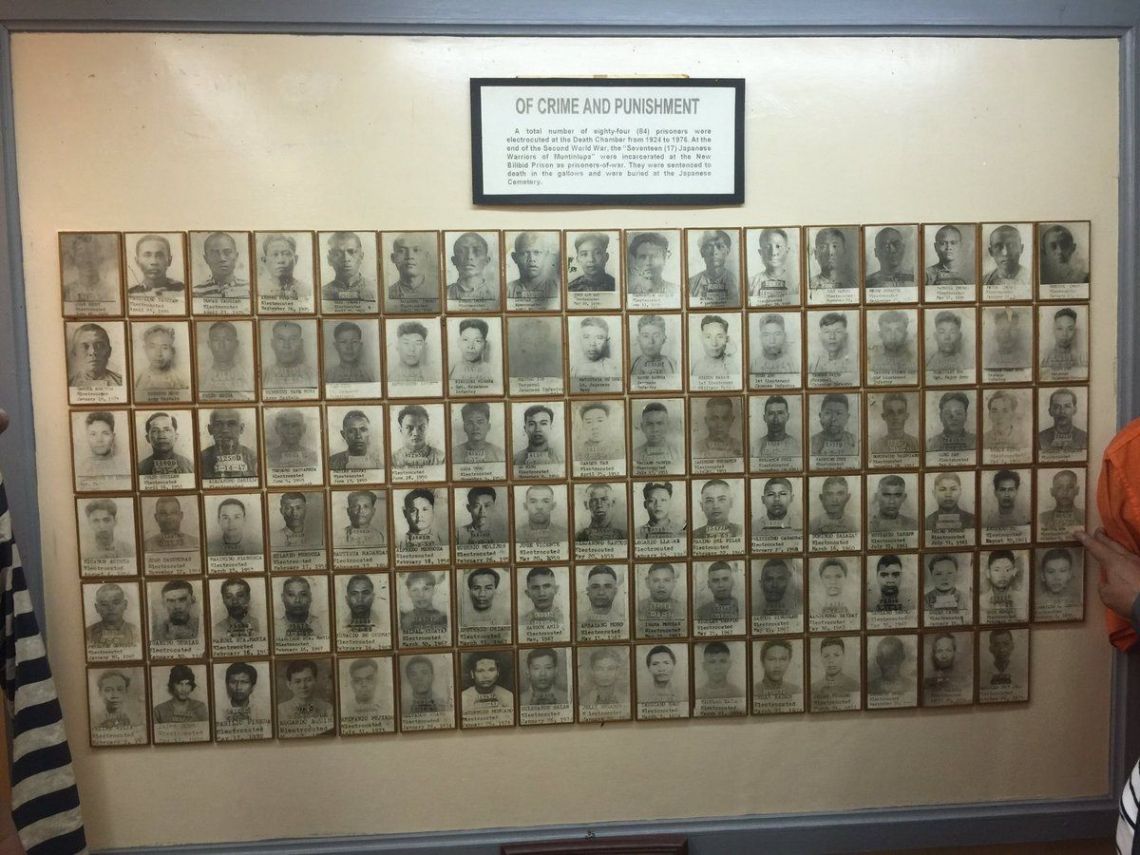

A tarpaulin in

the Marcoses’ World Peace Center in Batac, Ilocos Norte bearing a

staple claim in the Marcos propaganda repertoire. Photo by Judith

Camille E. Rosette.

Marcos’s decision resulted in a two-year death penalty moratorium. But

contrary to Pacis’ hope, he simply delayed the execution of

convicts. He started with the triple killing of Jaime Jose, Basilio

Pineda, and Edgardo Aquino, rapists of actress Maggie de la Riva.

Their execution on May 17, 1972, had live radio coverage, and the

usual handful of witnesses in an execution reached almost 50 in

number. Eight months later, he had Lim Seng executed by musketry in

public with live radio and television coverage (and later replayed in

cinemas). Then after a triple execution on March 21, 1974, he

stopped.

State executions started again with Leo Echegaray on Feb. 5, 1999.

Macapagal-Arroyo had marched in a rally calling for his

execution. She would later explain that she was there for the victim

to have justice and not for the death penalty to be imposed. Yet this

instance was quite symptomatic of how she ended up abolishing the

death penalty: via flip-flops. As reported by PCIJ on June 24, 2006:

Shortly after she was sworn in as president in 2001, Arroyo announced that

she was not in favor of executions and proceeded to commute the

sentences of 18 death-row convicts. But a few months after, on Oct.

15, Arroyo announced in a meeting of Filipino-Chinese businessmen

that she would resume executions due to the rise of kidnappings that

targeted the Tsinoy community.True to her word, on December 2003, Arroyo lifted the de

facto moratorium on executions issued by former President

Joseph Estrada.Two-and-a-half years ago, Arroyo said she would allow the death penalty for

convicted kidnappers and drug lords. But no death sentence has been

carried out under her administration so far.

In 1993, Arroyo chose to abstain from voting on a bill that would

reimpose the death penalty for certain heinous crimes.She said she was “torn between a constituency that clamors for it

because of the sickening examples of heinous crimes and a

conscience.”

GMA News ended up with a rather lengthy timeline just trying to keep up with Macapagal-Arroyo’s dexterity in navigating a potentially controversial issue.

But she did sign into law RA 9346 that prohibited the imposition of

the death penalty. It’s the very law that Duterte and his

legislative henchmen, her current political allies, would very much

like to undo.

To pardon or commute a sentence, as pointed out by legal scholars, is

not a private discretion of the chief executive. It remains, as

argued by Romulo Gatilao in a 1959 Philippine Law Journal

article, “a benign expression of the sovereign will.” But

making that sovereign will apparent is a president that must wrestle

with his or her inner demons and saints on whether to save a life or

take it.

A president may campaign and clamor to kill criminals. He may do so

secretly through deputies and death squads. But giving the green

light to kill convicts is political theater in and of itself. The

braggadocio sputters into a studied silence. A pretense for

equanimity is played out before denying an appeal or making a

reprieve lapse. The state kills on schedule, though a momentary delay

is desired to show that a president agonizes over life and justice,

retribution, and death. Pleas for clemency offer a president a chance

for a dramatic pause. Then in an ever-calculated manner, he signals

for death to descend. He gets to be a killer himself.

(Joel F. Ariate Jr. is a university researcher at the Third World Studies Center, College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of the Philippines Diliman.)